How Profound is the Air

Baumschlager Eberle has given architectural form to a verse of Jorge Guillén which Eduardo Chillida made popular: “How profound is the air.” The sculptor met the poet in Harvard in 1971, and that encounter sparked a friendship, an artist’s book, and a series of sculptures that took their title from a fortunate line of ‘Más allá,’ the poem that introduced Cántico in 1928. When the two have disappeared, Dietmar Eberle brings new life to the verse where Guillén – who sang the lyrical materiality of the building – and Chillida – who studied architecture several years – converge, and this with a body of work that reconciles density and atmosphere, depth and air: the compactness that urban sustainability demands and the hygrothermal control that permits reducing or eliminating energy use; the thermal inertia that compensates daily or seasonal oscillations and the ‘exact breathing’ that regulates the maximum presence of carbon dioxide.

Twenty years back we already admired the studio of Vorarlberg for its deep-bay residential projects, organized in concentric layers that allowed designing extremely compact buildings, with the subsequent cost saving (due to the reduction of the facade-floor ratio) and the no less significant energy saving (because by improving the form coefficient, the enclosure exposed to the weather is smaller). In fact, Baumschlager Eberle opened the monograph we published then, gathering twenty residential developments in different European countries, with a lucid text that underlined the regional roots of collective housing, marked by social, technical, and normative factors; the importance of construction details and the learning process that helps refine them; and the necessary dialogue with the agents involved in this type of project – developers, authorities, and occupants – aiming to reconcile functional demands and formal preferences.

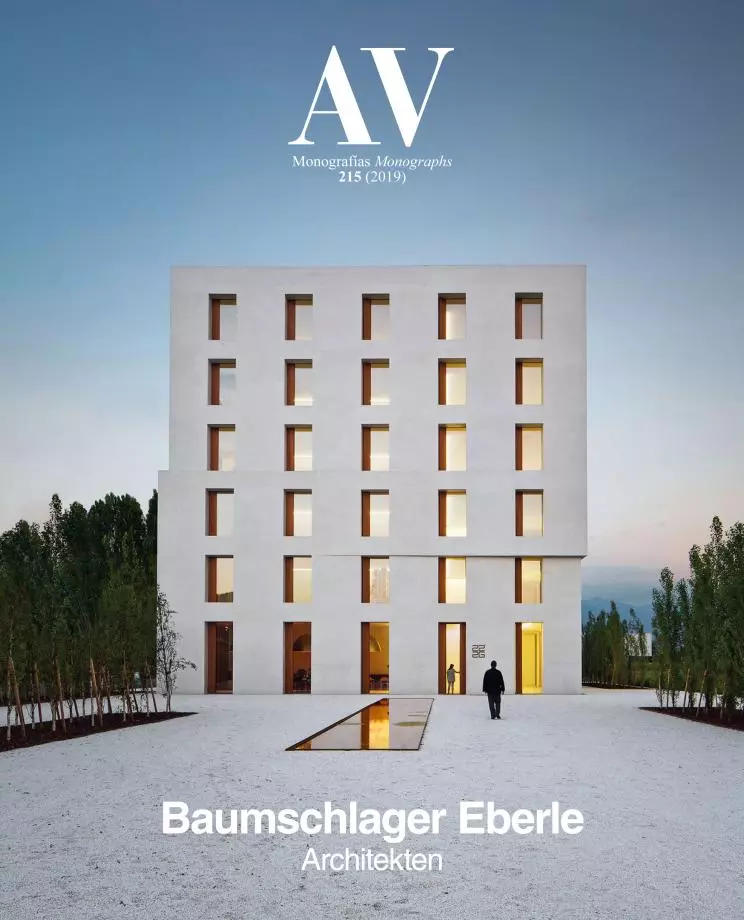

Today, that admiration has extended to the decision to transfer Eberle’s research and teaching at the ETH on densities and atmospheres to actual buildings, from the central studio in Lustenau and also from those in Vaduz, Vienna, St. Gallen, Zurich, Hong Kong, Berlin, Hanoi, Paris, Hamburg, and Cracow. A decade ago, the architect and professor announced that he was set to design the building for his office in such a way that it would need no energy at all, and that visionary endeavor took shape in 2013 as an efficient and exquisite cube that we published in Arquitectura Viva under the title ‘Atmosphere without Machines,’ in an issue that defended the importance of thermal inertia for sustainability under the motto ‘Mass is More.’ The verse of Guillén inspired Chillida to create architectural sculptures where space and air are materials just as essential as alabaster or iron, and Eberle places his compact and atmospheric prisms under that dark light.

Luis Fernández-Galiano