Advent Homily

The global market for signature architecture is currently experiencing an inflationary growth that devaluates the publicity value of spectacular works.

There is more vinegar than wine in celebrity architecture. Borrowing Ratzinger’s evangelical metaphors, the European city is a vineyard devastated by wild boars, a cultivated construction destroyed by economic and mediatic forces that have imposed their animal appetite on the plant-like slow pace of urban continuity, offering the compensatory shine of signature architecture as orientational or identity-defining placebos in the mutating territory of globalization. But the proliferation of these landmarks and icons erodes their curative fiction and makes the publicity impact of their trills fade out in the din of the times, their promesse de bonheur going up in smoke. The philosopher Ortega y Gasset deplored the fact that the parliamentary debates of his time were waged between wild boars and tenors, and today’s urban dialogues may likewise be a battle between money that assaults and artists who sing, even as the wine of their voices, turned vinegar, no longer makes us drunk. Going back to Benedictine enological theology, after the destruction of the vineyard by wild pigs, symbolic architectures are nowadays elaborated with grapes of the jungle, which produce more hangover than euphoria.

The Palace of the Arts, inaugurated and closed down immediately after to improve the visibility of the audience in the auditorium, is the last piece of the vast complex built in Valencia by Santiago Calatrava.

Negative reaction to emblematic works is due not so much to their traditional role of propagandists of power, nor to their contemporary function as movers of the tourist industry. It is due to their uncontrolled proliferation, with the inevitable effect of diluting uniqueness and diminishing quality, when star-architects cease to be able to keep high the excellence bar. What else happens in contemporary art museums when the formulaic repetition of collections – presided over in succession by a Moore, a Chillida, or a Turrell by the entrance – deteriorates both the specific profile of the institutions and the generic value of the works, which are produced under the pressure of a sleepless market. In architecture, such metastasis of icons has also nourished protectionist protests, such as the one led by Will Alsop when London won its bid to host the Olympics, through a collective manifesto advocating the protagonism of Britain’s new generation in the projects for 2012 so that these do not fall into “Dutch or Spanish hands”; or the one formulated in an open letter to Ciampi and Berlusconi from 35 leading architects, among them Vittorio Gregotti and Paolo Portoghesi, that speaks of the proliferation of commissions to foreigners endangering the continuity of an architectural investigation initiated in the thirties that is for Italy an “unrenounceable cultural resource”.

The Scottish Parliament, object of an inquiry by the institution itself due to its budgetary overruns, is a posthumous work by Enric Miralles, completed by the studio directed by his widow, and awarded with the Stirling Prize.

However petty some of these demands may be, they are in tune with the emotional climate of a Europe that is unable to compete with Asia, that is demographically aged, and that through recent constitutional referendums has expressed fear over enlargement toward the East – the famous Polish plumber of the French consultation – or the entry of Turkey – with the impact of the Islamist murder of Theo van Gogh hovering over Dutch ballots. They also vibrate in resonance with a general feeling of withdrawal, the result of a sense of insecurity produced by globalization, which has given rise to a return to the more immediate fidelities of village and tribe, and a revival of regional identities that take on a new cultural and political protagonism. But their basic fuel are widespread anger at the excesses of the star system, a general fatigue with vedettes who do not always deliver the quality expected, and the evidence that local professionals often benefit from the comparison. (This is not exactly the case of the authors of the two manifestoes mentioned above: Britain’s young architects, besides scorning foreigners, have to contend with the generation of the two high-tech lords, Foster and Rogers, whose merits cannot be compared with those of their detractors; and it has a while since the Italian veterans last built anything comparable to the work of the international stars they are trying to exclude from their country.)

The protectionist tide arrives in Spain toned down by the feeble chauvinism of a country whose self-esteem was injured by the prolonged isolation imposed upon it by the Franco regime, and whose opening to the rest of the world has always been associated with modernity and freedom. But it also arrives here driven by the perception of an unequal exchange (despite wide international recognition, we import more architectures than we export), by the building of client networks in territories of strong identity, and by a lukewarm disappointment with the latest crop of signature architectures, not always at a par with the generosity of budgets or the reputation of their authors. In the exhibition on Spain’s new architecture that opens in February in New York’s Museum of Modern Art, a great tribute to the excellence of current construction here, nearly a third of the works are by foreign architects. This shows both the breadth of the outlook of Spanish institutions (which make up the greater part of the clientele), and the fascination that figures of the international scene feel for a country where they have not always been able to work in the best conditions, whether because of the usual uncertainty of programs in public commissions or because of the no less frequent problem of budget imprecision, but where they have also enjoyed a degree of media popularity and political deference that is much less common in other places.

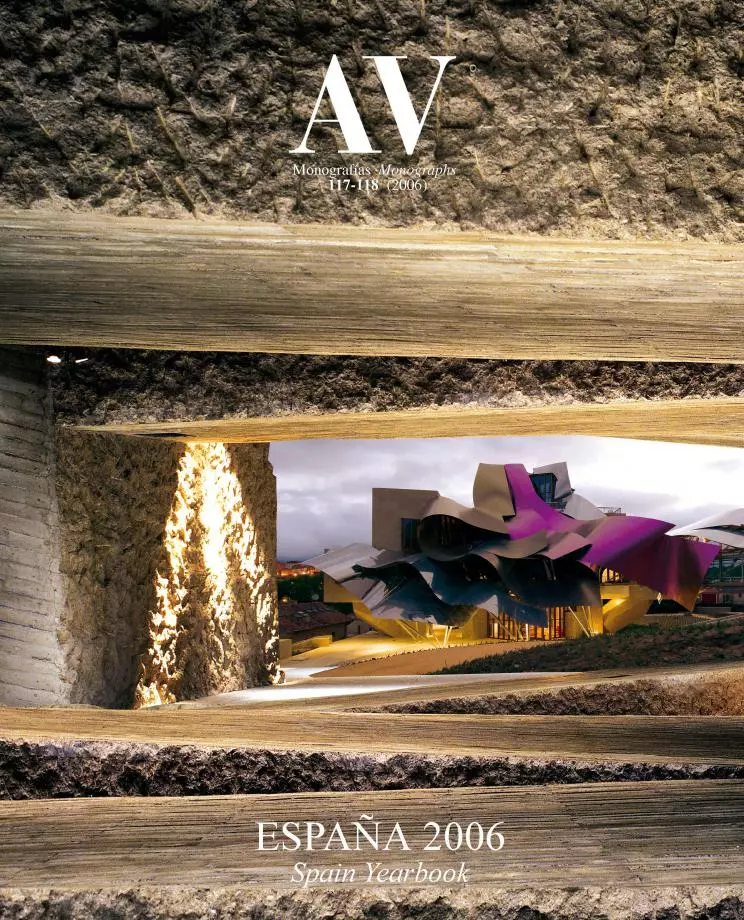

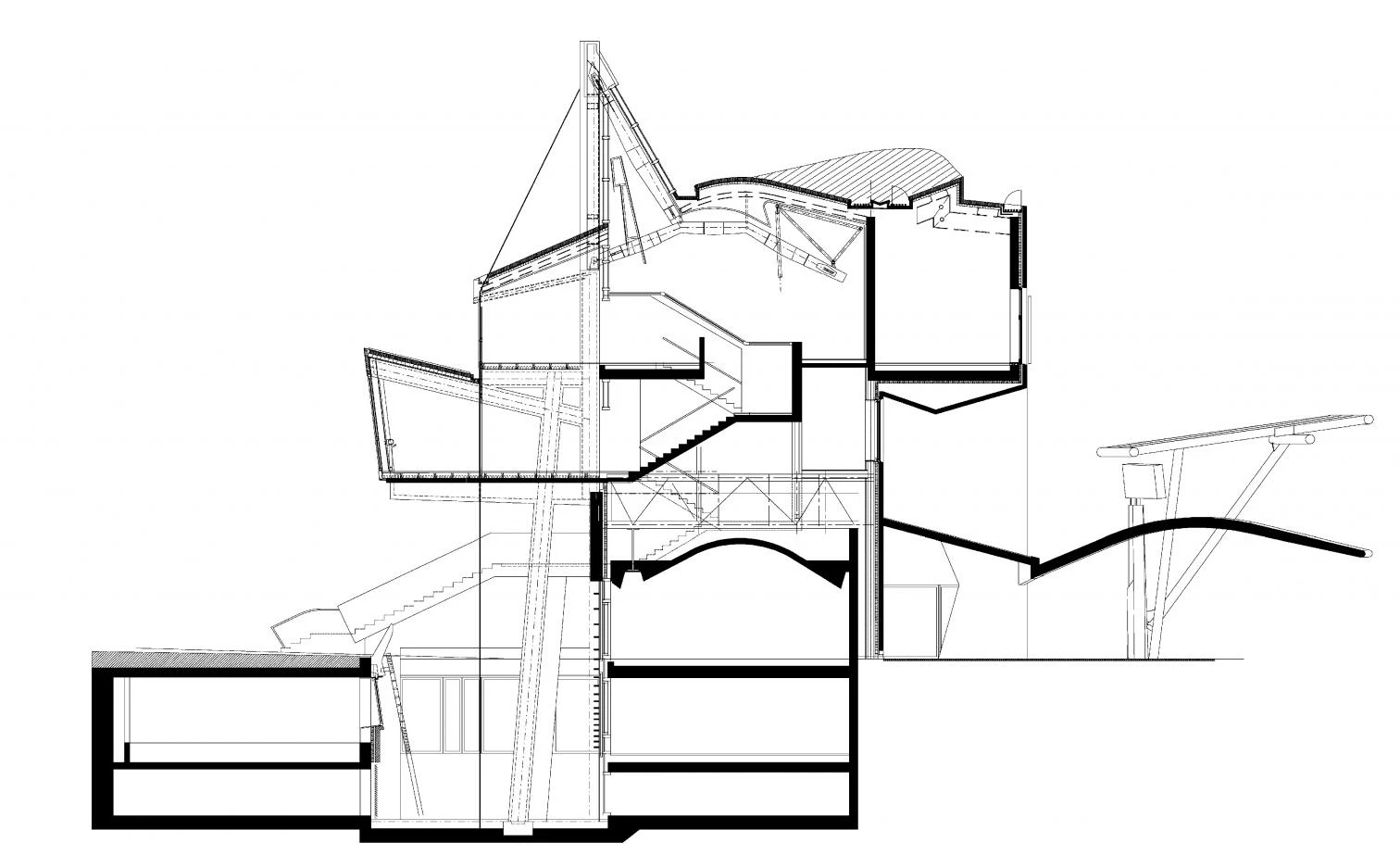

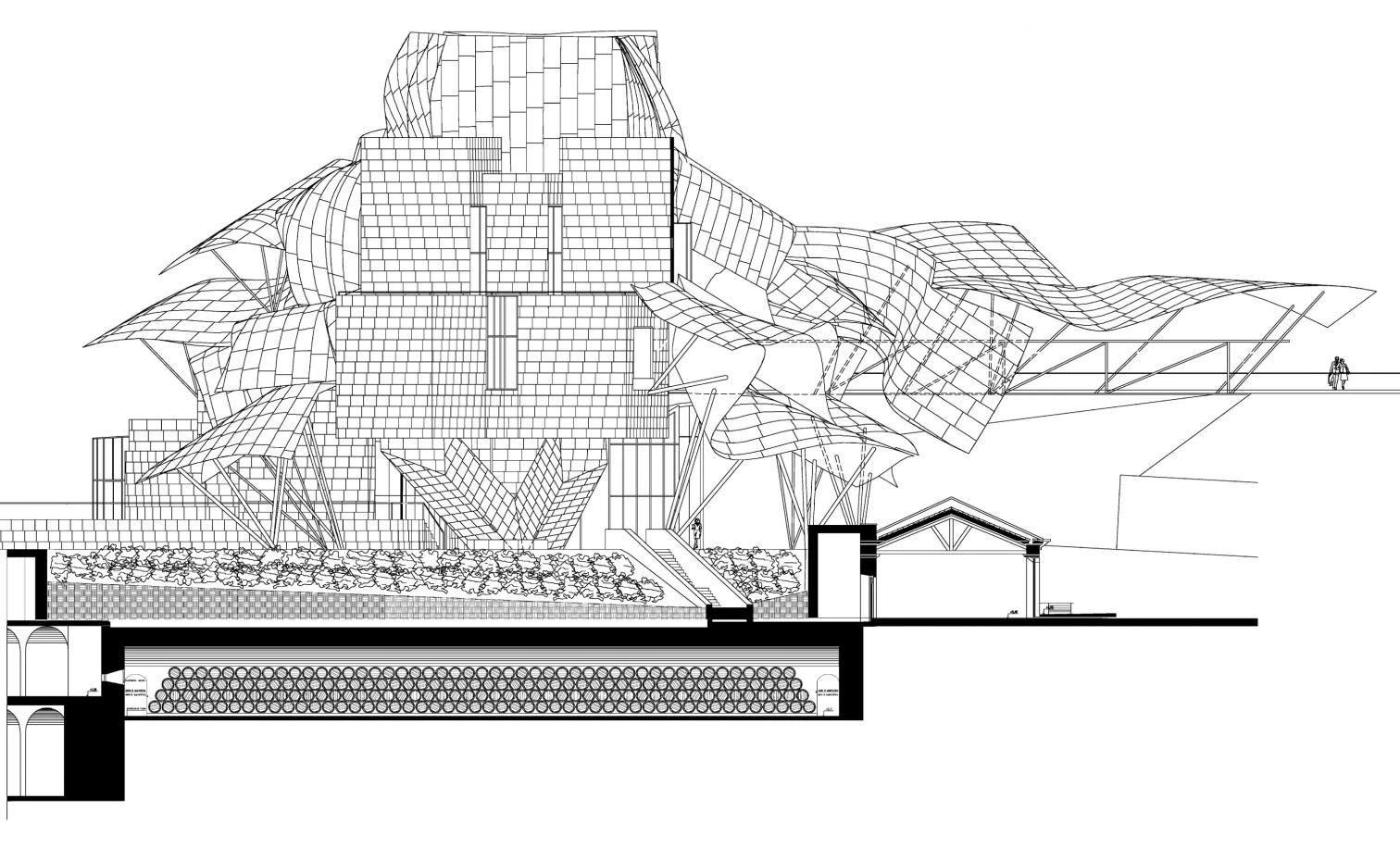

The Marqués de Riscal complex, where signature architecture is used to extend a winery’s activity with a hotel, a restaurant and a cultural center, is Frank Gehry’s second building in Spain, after his mythical Guggenheim.

However much we censure the formal or economic extravagances of signature works, we must remember that architects try to give more than they have to, offering society more than society asks of them, and only those who have renounced such self-demanding integrity that is the pillar of professionalism can be sequestered by the censurable smugness of one who gives less than his prestige promises. Sometimes there are accidents, as in the Scottish Parliament, a work of dramatic beauty that represents democracy with unexpected forms, where the near-simultaneous passing away of the architect and the politician who acted as his client triggered a budgetary loss of control that gave rise to an inquiry of the very institution, without this financial derailment preventing Enric Miralles from posthumously winning the Stirling Prize, the highest distinction awarded a building by the collective of British architects. But no major project is immune from journalistic polemic and political scandal, and as much the Sydney Opera House as the Pompidou Center or the Guggenheim-Bilbao Museum were capolavori received with the same din that now surrounds the City of Arts and Sciences of Valencia or the City of Culture of Galicia, two titanic works that may one day be their authors’ masterworks, even if today we see only the excess of their scale with a guilty conscience that makes wine go sour.

If signature architectures ought to tone down, surely it is because we have decided to build fewer buildings and more city. Only from the perspective of the physical and temporal continuity of the urban realm can we hope to channel the turbulent currents that transform the material world, and only from the priority of the collective can we attempt to ride out the storms of history that shake our social universe. But it will not be because a generation on the rise or in decline clamors for protectionist measures against foreign stars, or because the main economic agents of the building sector prefer to deal with meeker professionals. Star architecture is a demanding sector, and architects who do not live up to expectations suffer an immediate erosion of their reputations in the professional or academic environment that later transfers to the public at large and their clientele. It is in this lag that most pathologies proliferate, if we do not classify as such all the follies that every generation builds with the unanimous conviction that it has found the philosopher’s stone, when often its works are but the product of aesthetic or intellectual fashions that disappear as suddenly as they came. But the decadence of some celebrities and the intrinsic fleetingness of fashion come together these days to raise an architectural alarm that resembles the ‘profit warnings’ leading corporations publish to inform the market of their profits being lower than predicted, and that here would have deserved the title ‘advent admonition’ had I not feared abusing alliteration and rhetoric.