Gottfried Böhm, 1920

A Sculptor Architect

In observance of Gottfried Böhm’s centenary, much is made of his being a grandson, son, husband, and father of architects, with the possible implication that his choice of profession, and practice thereof, was a consequence of the generic dictates of a dynasty with firm roots in the local culture of Cologne and its Catholic tradition. However, architecture was not Böhm’s first calling, nor his principal one. His real vocation was sculpture, in which, in the midst of World War ii, he received training at Munich’s Academy of Fine Arts while studying architecture. If we think of Böhm in terms of both facets of his, we can better understand his work, a lifework until now among the least known about, and least understood, within the collective oeuvre of the select circle of Pritzker laureates.

Particularly enlightening is the very first building he carried out on his own while still collaborating with his father, Dominikus Böhm (1880-1955). This was the St. Columba chapel (1947-1960) in Cologne, which gave a home to the ‘Madonna in the Rubble,’ a medieval carving that survived the war bombings and was found among the ruins of a Gothic church, to then become an object of fervent popular adoration. Young Böhm’s intervention was an octagonal structure framing and protecting the figure of the Virgin. The result evoked a succession of inverted, hanging Gothic vaults which would surely have delighted Gottfried Semper and Antoni Gaudí.

Maria Königin des Friedens Church

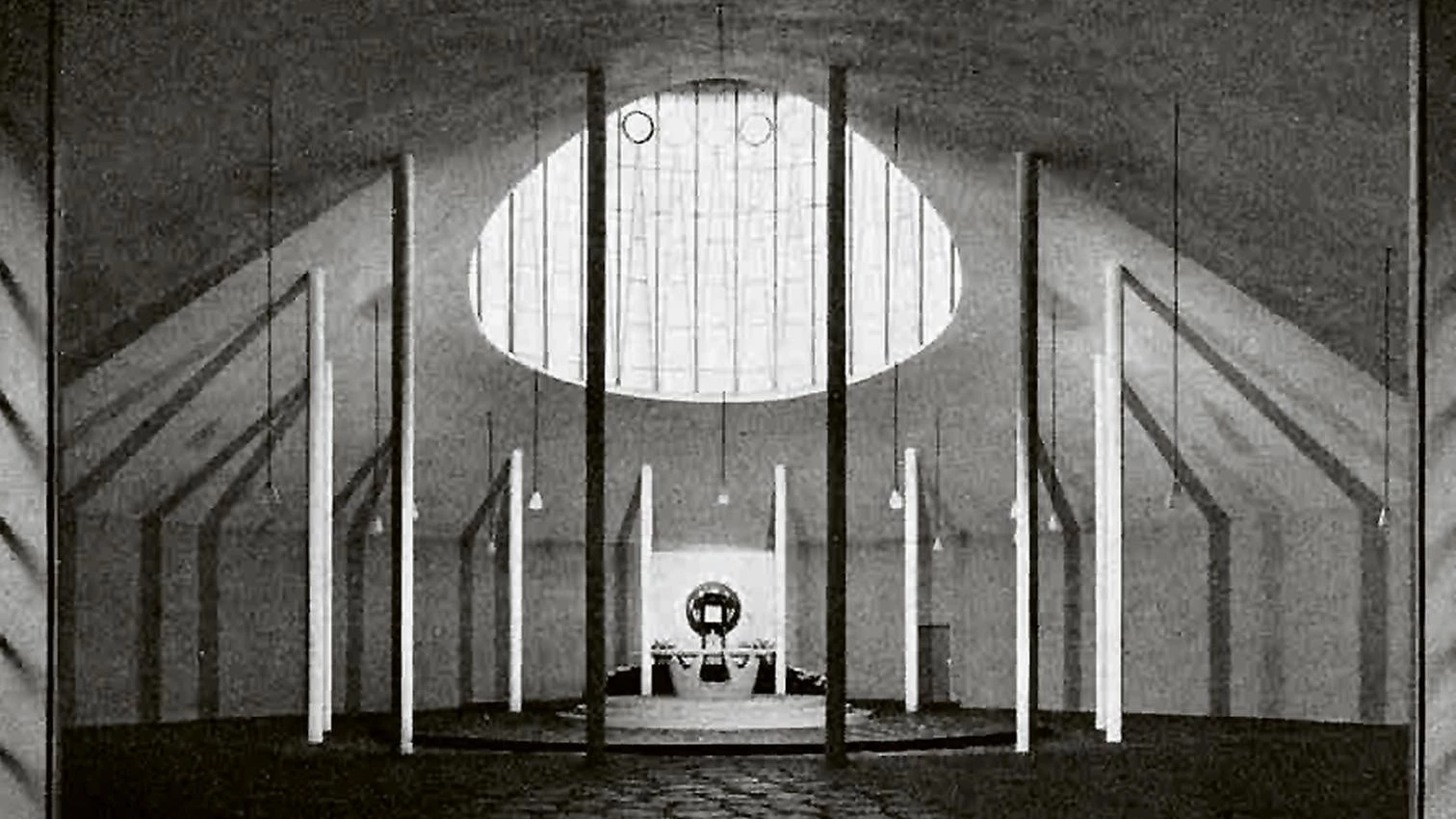

The success of this opera prima – small but with huge social and cultural repercussions, and now respectfully integrated into the Archdiocese of Cologne’s Kolumba Museum, as renovated by Peter Zumthor – began a period of exploring the architectural potential of hanging membranes. The experiment led to some articles of a theoretical sort that elicited critiques by Frei Otto in his published dissertation, Das hängende Dach (1953). To be sure, Böhm was not so much interested in structural optimization as he was looking for new attributes, and this comes to the fore in brilliant works of those years, such as St. Albert in Saarbrücken (1951-53), with the elegant vaulted sheet of its roof, suspended among organic buttresses, or St. Paulus in Velbert (1953-55), with its interplay of penetrations of hanging membranes and transparent volumes. Considering such relish for the lightweight and rational, it is hard to believe that barely a decade later, precisely in Velbert, in the hamlet of Neviges, he built its architectural antithesis: the crystalline block of carved concrete of Maria Königin des Friedens Church (1963-73), without a doubt his most acclaimed work but also the most criticized, given its archaic monumental boldness in times of technological and social revolutions.

Maria Königin des Friedens Church

From the huge dimensions of the church, which can take in 8,000 pilgrims, Böhm deduced the scale and the landscaping and urban character of the complex. The interior of the holy mountain is, more than a cavern, a public square. Using everything, all the way to the details of the lamps and flagstones, Böhm sought to express an urban calling and create a scenery that symbolized the community. Recurrent not only in his churches but also in his town halls and theaters, this theme is better understood if pondered against the backdrop of the bleak city centers of German reconstruction that the psychoanalyst Alexander Mitscherlich in 1965 dubbed ‘second destruction’ – this time not by war but by postwar architects and engineers.

Among the architects of a generation that had seen the material and moral devastation of Germany, Böhm was alone in looking for meaning and dignity, even consolation, in the symbolic values of architecture and the historical continuity of urban fabrics and imageries. He made this the core of his teachings during his period as professor of architectural design in Aachen. The synthesis he sought is also evident in the urban character of his basilica naves, in his city passageways, and in the spectacular lookout-domes of his postmodern period. The symbolic weight is clear in the studies that in the 1980s Chancellor Helmut Kohl tasked him to do for the Reichstag building’s reconstruction as seat of parliament of the Federal Republic of Germany. The domes proposed by Böhm did not win the 1992 competition, but in their transparency as well as in the catwalks overlooking both the urban landscape and the plenary hall below lie the keys to the success of the project that was eventually carried out by Norman Foster.

Expressionism, brutalism, and postmodernism are labels that prove of little help in understanding the work of this long-living and prolific sculptor-architect in its various stages. The only common denominator may be Gottfried Böhm’s search for both ethics and aesthetics in simultaneously sculptural and urban architectures capable of expressing collective values.

Joaquín Medina-Warmburg is a Professor of History of Architecture at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology.