From the Technical to the Thermal

Iñaki Ábalos graduated in 1978 from the Madrid School of Architecture (ETSAM), which in those years harbored two different traditions represented by two influential faculty members, Alejandro de la Sota and Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza. Sota’s disciples admired Mies van der Rohe, and their projects were guided only by the logic of construction; those of Oíza, for their part, revered Le Corbusier, and proposed an eminently formal approach, inspired also by the organicism of Frank Lloyd Wright. In his professional and personal path, Ábalos has moved from construction to form, and therefore from Sota’s example – the technical and geometric rigor of which marked his long association with Juan Herreros – to Oíza’s legacy, whose expressive freedom can be found today in the parametric projects carried out with Renata Sentkiewicz, collaborator since 1997 and partner after his split with Herreros in 2006.

An architect who has always been interested in the intellectual dimension of the discipline, evidenced in essays like Technique and Architecture in the Contemporary City (with Juan Herreros), The Good Life and Picturesque Atlas, Ábalos has drawn on the political liberalism of John Rawls and the philosophical pragmatism of Richard Rorty to relate his projects to contemporary thought, with a special emphasis on the relationship of architecture with nature and landscape, a circumstance undoubtedly stimulated by his early designs for the construction of water treatment plants. These professional works also sparked his continued attention to the picturesque, from Capability Brown or Frederick Law Olmsted to Burle Marx or Robert Smithson, an interest he has combined with today’s priorities in the field of sustainability to propose an aesthetic based on energy flows, in search of what he calls ‘thermodynamic beauty.’

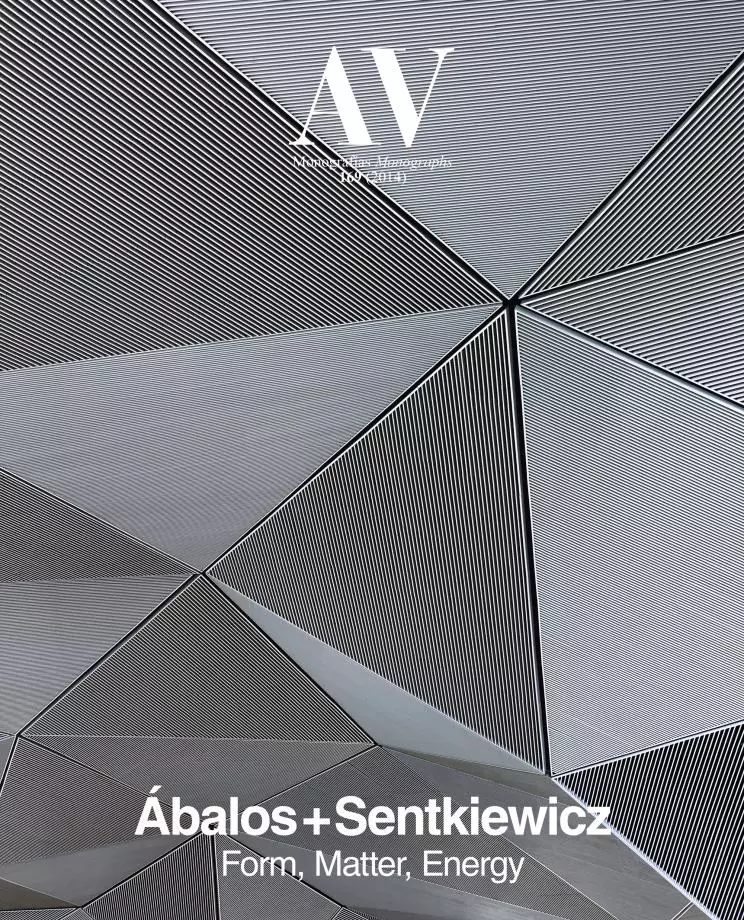

This aesthetic extracts its formal complexity and its compositive variety from the use of digital tools, which effect the transfer from theory to practice through algorithms that generate organic or crystallographic geometries. In this reflection on the relationship between matter, form and performance a leading role has been played by Sentkiewicz, an architect and engineer trained in Krakow who would very soon take on responsibilities in the studio, and who has been a driving force behind Ábalos’s journey from construction to form, and from the technical to the thermal: an evolution that brings together the current voices demanding attention to sustainability and landscape with the faint echoes of Oíza who, back from America, became in the 1950s a teacher of building services in Madrid, and was heard thermodynamically reprehending Gutiérrez Soto for his Ministerio del Aire: “Don Luis, less stone and more cooling power.”

Luis Fernández-Galiano