From Rigor to Versatility

Modular Houses: Geometry and Construction

Modular architecture is still one of the most fascinating themes for architects from the perspective of rational thought. It evokes the childhood construction games that are so fondly remembered. The kit of parts offered endless combinations, but instead of putting together small bricks of wood and plastic, now it is possible to assemble structurally independent modules with countless possibilities.

The attraction to seriation and the production chain dates back to the first decades of the century, and its origin can be found in the fascination for industry with the revolution that Henry Ford brought into the manufacturing processes. At that time the belief was that mass-produced prefab housing would reduce costs and, just like any other consumer good, give large sections of the population access to a very broad market. However, developments over the past century show that the automobile and housing industries have traveled along very different paths.

Architects since classical times have always worked under the premises of modularization and dimensional coordination, but the concept of modular architecture did not appear until the 20th century. Prior to that, the first surge of prefabrication came about with the Gold Rush in the United States in 1848; two years later, only in the New York area, more than 5,000 houses were transported to California to face the new migratory needs.

Modulation and Prefabrication

In the early 20th century, the commercial expansion of prefabricated housing was such that there was even a houses catalog in the United States, like the ones of Sears Roebuck & Co. of 1910, which offered wooden houses. The irruption of reinforced concrete in construction also permitted the development of new solutions, such as the mixed system by Frank Lloyd Wright of 1920, which combined prefabricated concrete with on-site works.

The boom of prefabricated housing took place after World War II, responding essentially to two factors: the need for mass construction in a very short period of time, and the industrial development of production and transport means. The most prominent architects of the 20th century participated in the development of modular housing, convinced that architecture should adapt to technological progress through the industrialization of the building process.

Heavy prefabrication with concrete panels was the showcase of European reconstruction from 1950 on, especially in Eastern Europe, where cheap, mass construction was the premise. Unlike concrete, light prefabrication evolved in the form of metal panels with framework structures. The key exponent was Jean Prouvé, who designed the famed prefabricated kitchen and bathroom modules, and was also one of the forerunners of the use of production methods with light material components.

After its Civil War, Spain had the same housing needs as the rest of Europe. To address them, in 1949 the Instituto Técnico de la Construcción y del Cemento, directed by Eduardo Torroja, proposed an International Call for Ideas to build 50,000 dwellings yearly. The call was a success, with 89 proposals from 17 countries that showed the state of technique at the time.

From the 1970s on, due to the economic crisis, drop in housing demand, and regulatory enforcement, the development of modular construction came to a sudden halt. The last two decades have been marked by the shift from closed systems to the open prefabrication of components, which makes for greater adaptability to market needs, and improvements in logistics and transport have increased the scope of action of prefabrication factories.

Seriation and Versatility

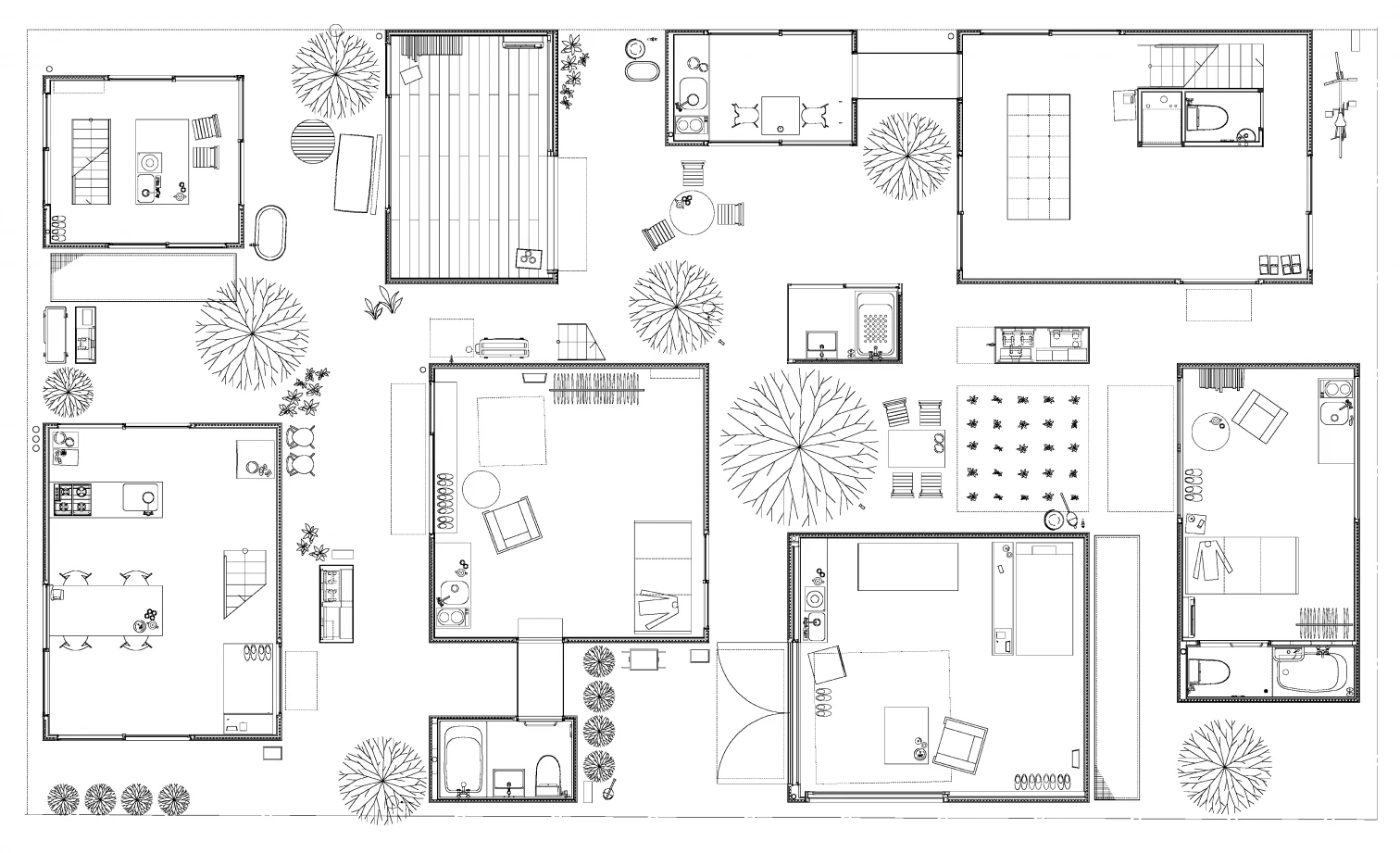

The key feature of modular houses is that every piece in the design is structurally autonomous, usually resorting to heavy solutions – with concrete walls for cladding, bearing or self-bearing, that are put together with dry assembly systems – or to light metal or wood structures, screwed or hammered on site. Manufacturers of precast concrete elements or metallic profiles find in complete solutions a new market in which to develop their products, proposing a broad catalog of more or less customizable parts. The Galician manufacturer of precast concrete parts Aplihorsa proposes an amusing game in its catalog. With around twenty basic modules that include certain predefined spaces, it adds some ten extra modules that offer great versatility for the final solution, completed with load-bearing perimeter walls of exposed concrete and hollow core slabs.

Generally speaking, in the field of construction prefabrication stems from the need to transport a building in parts to a place where, for different reasons, it cannot be built using conventional methods, and it is the perfect excuse to play with the building components. The repertoire of technical solutions, for enclosures and for interior distribution and finishes, are the same as those used in traditional construction, except that they are determined by the adaptation to the base module. This permits combining blind and glass walls, replacing facades with party walls, and the serial addition of other modules, always starting from dimensional coordination and adjustment to the base modularization.

Como mecanismo de control geométrico, la modulación permite soluciones constructivas óptimas susceptibles de aplicarse en diferentes contextos, pero también puede ser un mecanismo de exploración formal.

The transportation of small modules that are then assembled on site is the most usual system, provided that transportation conditions allow. The Uruguayan firm MAPA designed a small shelter for Finca Aguy in Maldonado (Uruguay), juxtaposing two prefabricated modules of wood and steel, aiming to reduce the impact of construction on the environment.

Today’s modular solutions are marked mainly by their versatility when adapting to numerous conditions, both technical and of design. Such is the case of the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, by F415 Aquitectura, which had to gather classrooms and study areas in an urban setting. The bolted metallic structure and the polycarbonate and perforated sheet enclosures create a very light structure that can be disassembled and recovered.

Industrialized systems have a great advantage: after exhaustive and detailed planning, costs and time are reduced considerably with regard to traditional construction. This has been possible of late thanks to a reduction of investment needs in prefabrication factories, as well as the reduction of the volume of work needed to make production profitable. Thanks to open prefabrication by components, modular construction allows adapting one design to different environmental and functional factors, and with this the adaptation to the architecture of the place.

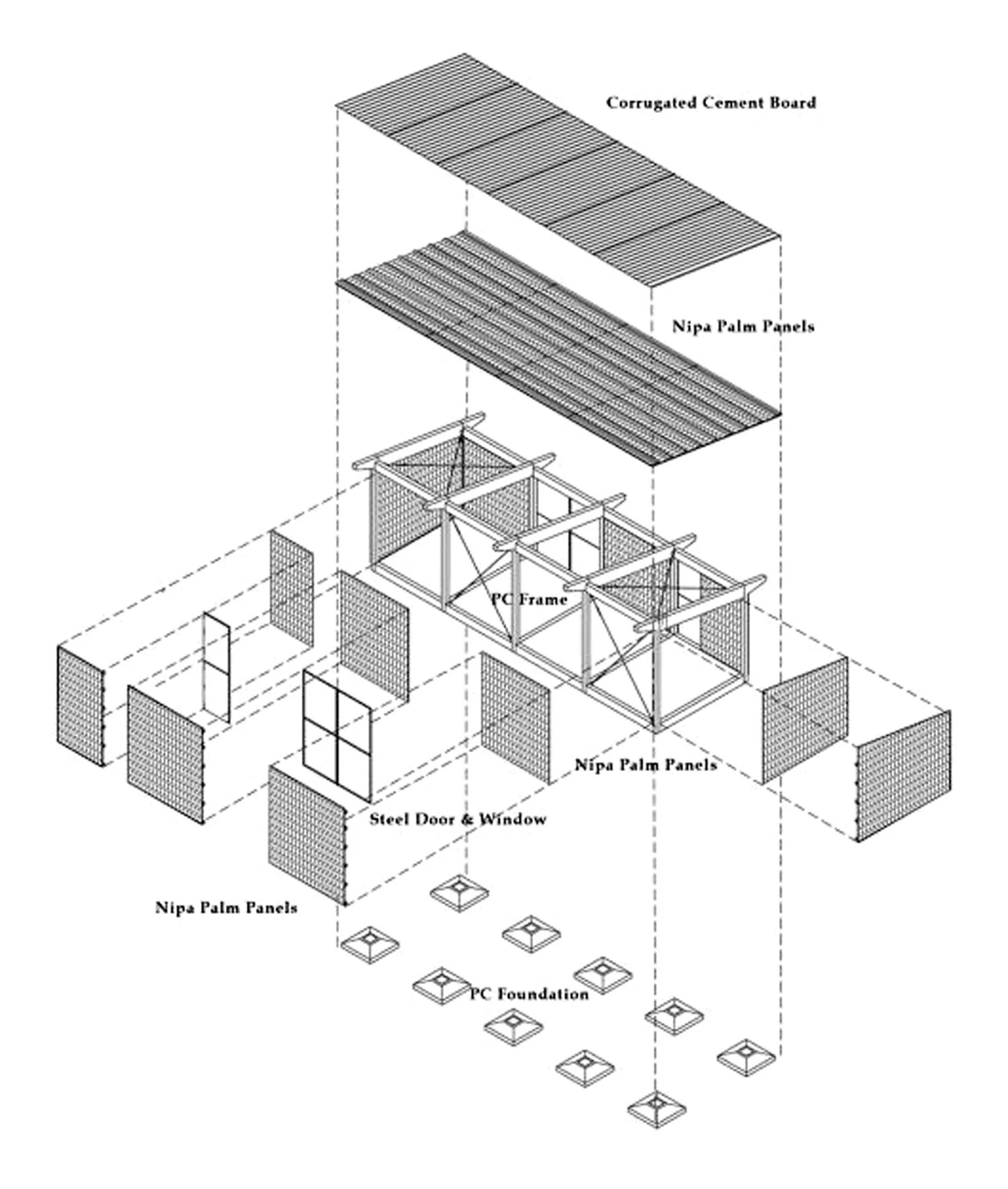

Light solutions, generally using metal and wood, have the advantage of minimizing the need for foundation laying and their impact on the ground, thereby reducing the cost of those items. This is essential when designing very low-cost houses, such as House S, by Vo Trong Nghia Architects, with their proposals for the rural populations in Mekong Delta (Vietnam). Both in the first prototype with the metallic structure and in the second one of concrete porticoes, the system is based on the modular combination of enclosures and partitions with very simple joinery. Moreover, light elements can be transported by water in very small boats.

Architecture of Emergency

Architecture of emergency is also one of the fields where modular construction has been applied with greater success. Some proposals, such as the RE:BUILD system designed by Iranian architect Pouya Khazaeli and the British Cameron Sinclair and developed by the Italian manufacturer Pilosio, make it possible to build very economical modules by combining scaffolds as loadbearing structures with metallic grille enclosures that serve as formwork for different types of natural materials. In the case of the refugee camps of Za’atari in Jordan, sand from the desert itself has been used, while a clinic in Mogadiscio (Jordan) will be built with gravel from a local quarry.

Some solutions are designed to be mobile. This is the approach of Koda House, a micro-dwelling of 30 square meters that the Estonian collective Kodasema has designed to be disassembled and reassembled in seven hours. This closes the circle that goes from geometric and constructive modularization to fast assembly on site, passing partially through the factory.

David Mencías Carrizosa is a hired researcher at ETSAM-UPM.