Vanity Fair

Transformed into media stars as bright as the Iraqi Zaha Hadid, the current popularity of architects contrasts with their lack of influence in urban matters.

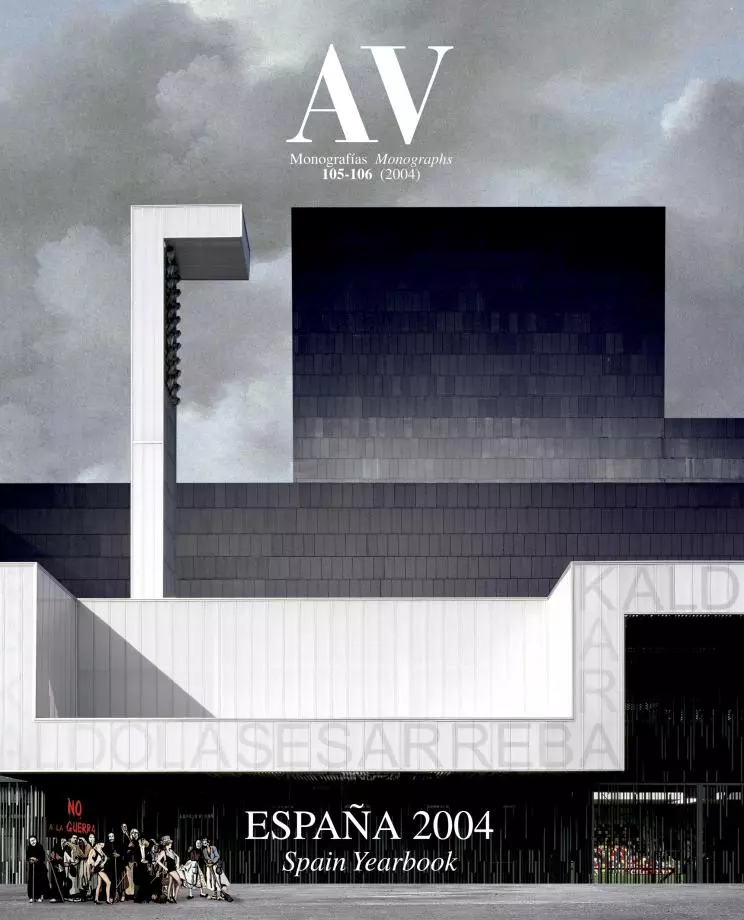

If there are 360 degrees, why use only one?” Zaha Hadid chose this vague declaration of disdain for the right angle to promote her exhibition in Vienna’s MAK, which opened on May 14, two weeks before Barcelona saw her receiving the Mies van der Rohe Award for her intermodal station in Strasbourg, and fewer than four before Cincinnati inaugurated – on June 7 – its Center of Contemporary Art, her first American commission ever and perhaps the most important of her career. This sculptural mass of concrete and aluminum that rises on a corner of a Midwestern city’s confusing center is surely to date the most ambitious execution of, in Newsweek’s words, “Design’s Hip Diva”; the most urban work of an architect accustomed to building free-standing objects in open landscapes; and the most complex project of one who has managed to combine her formal language with tributes to historical constructions like the Whitney Museum (on the facade) and the flying stairs of the Van Nelle factory (in the vertiginous steel ramps of the atrium), with references to contemporaries like Eisenman or Libeskind (in the syntactic and musical piling up of prisms), and with salutes to her men-tor Rem Koolhaas (in the loop lifting the carpet of the pavement). But this rich rendering in different angles also illustrates the anecdotal nature of signature architecture, often reduced as it is to a picturesque accent in the unanimous environs of economic anomy and the single angle.

Shortly after receiving the European Mies van der Rohe award, Zaha Hadid inaugurated her first work in America: the Center for Contemporary Art in Cincinnati, a carved volume with a dynamic and zigzagging interior.

This same month of June, he who was Zaha Hadid tutor at the Architectural Association appears on the cover of Wired as guest editor of an issue entitled ‘Koolworld’: an ideological and graphic atlas of the 21st century through which the Dutch architect defends the virtues of Europe, situates the future in Asia, and expresses his disap-pointment with New York City, which is “no longer delirious”, as he described it in his mythical book of 1978. After the cancellation of his two big-time American museum projects – the Whitney extension and the new building of the Los Angeles County Museum –, The New York Times described the slimming of a “Design Star” who in a recent talk with Columbia University architecture students acknowledged being “defeated in New York”. But the Sunday supplement of the same newspaper still considers him – along with Eisenman, Holl, Mayne, Tschumi, Herzog & de Meuron, Hadid, and few more – one of the creators of space of the future; the public library he designed for Seattle already projects its faceted volumes in the heart of the city; and the closing of his Guggenheim Las Vegas not two years after it opened is attributable more to business calculations than to architectural factors. In the final analysis, the triumphs and tribulations of Koolhaas in America are less relevant than the circumstantial nature of his projects, miniscule gestures of provocation or pertinence which drown in the trivial and generic ocean of the contemporary city, making architecture, in the Dutch architect’s own words, “an activity that inextricably combines omnipotence and impotence”.

The iconic work Cloud Prototype for an Edition of 3, by the Spanish artist Íñigo Manglano-Ovalle (previous page) was part of the opening exhibition in this new venue for contemporary art, where no two rooms are thesame and where the hustle and bustle of the street pervades the itinerary: an extension of the ‘urban carpet’, the entrance floor guides visitors towards the full height atrium, crossed by a concrete and steel staircase.

The ‘Gotha’ of Glamour

Turned into superstars, architects appear on TV talk shows and fashion magazines. Libeskind comments on the design of his elk skin boots or the frame of his glasses, Eisenman shows what is in his refrigerator or is photographed in the bathroom of his Greenwich Village apartment, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown discuss their culinary habits or display the wardrobes of their Philadelphia house, and no article on Koolhaas fails to mention his Prada suits, in the same way that no interview with Zaha Hadid will overlook her Issey Miyake gowns. In 1996 Vanity Fair had the likes of Pei, Johnson, and Foster attired in models of their buildings, in a remake of the famous 1931 beaux-arts ball at the Astor Hotel in New York, and since then the circus of architecture’s Formula 1 has constantly graced the pages of the Gotha of glamour. The latest issue alone, for example, features Gehry’s latest work, an art center in the Hudson Valley; a group portrait of the 37 architects (including Richard Meier, Michael Graves, Zaha Hadid, Shigeru Ban...) who built on Long Island a contemporary version of the fifties California’s Case Study Houses; an evaluation of the figure of Eero Saarinen, the prematurely deceased author of the TWA terminal in New York’s Kennedy Airport; and a long article about the current misadventures of the Pritzker family that, among other things, shows the clan’s late patriarch giving out the medal of the architecture prize it sponsors (in the jury of which, by the way, was the late Gianni Agnelli, subject of another extensive chronicle elsewhere in the issue).

Paradoxically, this unprecedented attainment of popular recognition for architects takes place at the same time that they are being excluded from the making of major urban and territorial decisions. The same profession that for a good part of the 20th century was at the hub of the urban revolution, while flying under a mediatic radar, now graces all the screens but finds itself on the margins of the operations that are transforming cities and landscapes. As the giant corporations that wrestle obscenely for contracts know, the great commission of the moment is not New York City’s Ground Zero, a stage full of architects in the limelight, but the reconstruction of Iraq, where the leading players go by the names of Bechtel, Fluor, Parsons, Washington, Berger, and Halliburton. And one has to read the Fortune magazine’s report on the latter – a company headed up to August 2000, apparently not too successfully, by current U.S. Vice President Dick Cheney – to grasp the intimate logic of the process from the the entrails of the system. Initially left out, British firms complain bitterly in The Architects’ Journal, adducing both their country’s cooperation in the deconstruction of Irak from the very beginning of the war and its greater experience “in designing architecture that respects Arabic traditions”. Perhaps this is the reason why the London-based Iraqi Zaha Hadid has told El País that she “would be delighted to participate in the rebuilding of Iraq”, and that this well-intentioned declaration calls for an examination of conscience.

Are today’s architects adequately equipped to intervene in large-scale infrastructural operations?Or, on the contrary, do their qualifications limit them to the symbolic foam of physical transformations? Last May 9, in Cleveland, special police forces took seven hours to get hold of an armed individual who had killed a person and injured two others in the labyrinthian interior of a business school built by Frank Gehry. “There are no right angles in the building,” said the chief of police when trying to explain the long chase, “and we have always trained in rectangular premises.” Like Zaha Hadid – but unlike Gropius or Sert, who built in Iraq almost half a century ago – Gehry uses each and every one of the 360 degrees there are to address the complexity of the world, or probably just to represent it. The last bars of May bid farewell to Ilya Prigogine, a humanist scientist who theorized on chaos and inspired many architects of my generation with his explorations of new forms of order, and to María Teresa López, La chiquita piconera, muse of the Andalusian painter Julio Romero de Torres and popular erotic icon. The two main Spanish newspapers, El País and El Mundo, gave them equal obituary coverage, a photograph and three columns for each. Architects have dialogued with science in order to understand and transform the world, and now flirt with art so as to seduce with its sensual ember: those who deplore this transit should find consolation in the melancholy indifference that in the end blurs and flattens all.