Fanfare and Fantasy

The concert halls of Calatrava in Tenerife and Gehry in Los Angeles bring the contemporary trend of spectacular constructions to a new level of flair.

If architecture is frozen music, concert halls must be doubly so. Tenerife’s opened in September with a minor work of the Polish composer Krysztof Penderecki entitled Royal Fanfare, and there is indeed something of the music’s racket of metal in the defiant, screaming forms of Santiago Calatrava. A few weeks later, LA’s Disney Hall was inaugurated with a program that culminated with The Rite of Spring, the Stravinsky score that Walt Disney popularized by including in his 1940 picture Fantasia, and Frank Gehry’s work likewise seems to shake its volumes with an imagination that mixes animation and avant-garde. Fanfare and fantasy, the two auditoriums have much in common aside from being end-products of fifteen-year odysseys: the sculptural slant of their authors, the aspirations to become city symbols, and even the metaphors used by the media to herald their completions: both have been compared to ships and sails, both have been described in terms of wind and waves, and both concert halls, with their warm wooden claddings and exigent acoustics, have favored the mention of Stradivarius or Guarneri instruments

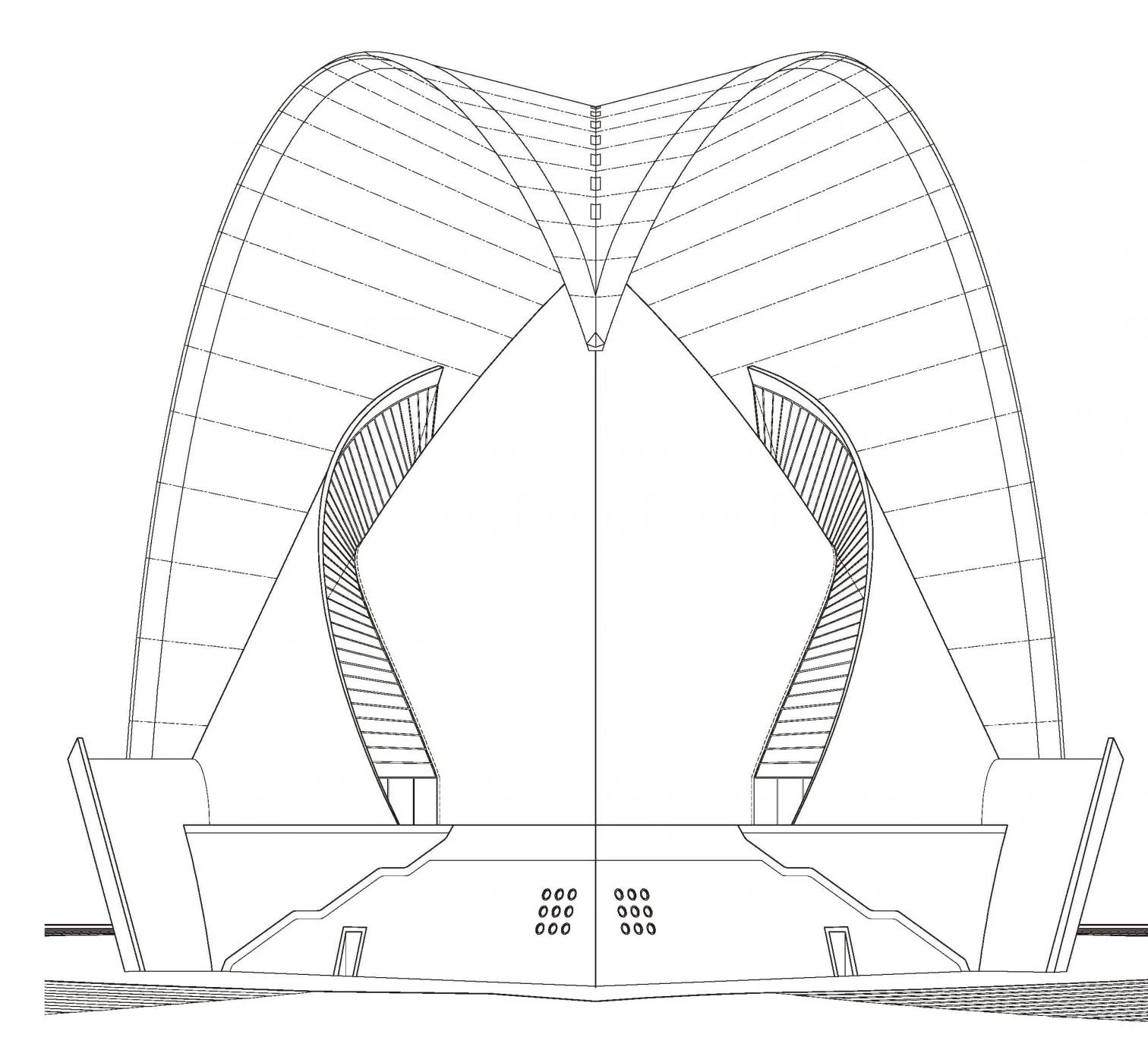

Raised by Santiago Calatrava by the Atlantic Ocean, the auditorium of Santa Cruz de Tenerife displays the memorable profile of the concrete wing that seems to float weightlessly over the pointed shell of the hall.

There is of course another bond between them, and it is that they are built to be the homes of exemplary orchestras. The Sinfónica de Tenerife currently under Víctor Pablo Pérez and the Los Angeles Philharmonic, directed by Esa-Pekka Salonen, are institutions whose brilliant track records promise programs of a rigor without which even the best musical architecture is in vain, for these buildings are made as much to be heard as they are to be seen. All this aside, they could not be more different. Both architects like to cite Giacometti or flaunt their biomorphic interests, but Calatrava’s naturalist imagery, like Saarinen’s or Utzon’s, feeds on organic symmetrical geometries and the still motion of articulation or flight, whereas Gehry’s expressionist mannerism, like Borromini’s or Scharoun’s, evokes the choral convulsions and oneiric scenographies of an enchanted forest. Tenerife, which the most skeptical will dismiss as a naïf remake of Sydney, can more generously be described as an optimistic still life of concrete beaks and wings, and Los Angeles, which the most cynical will see as a Bilbao on steroids, as a storm of steel petals.

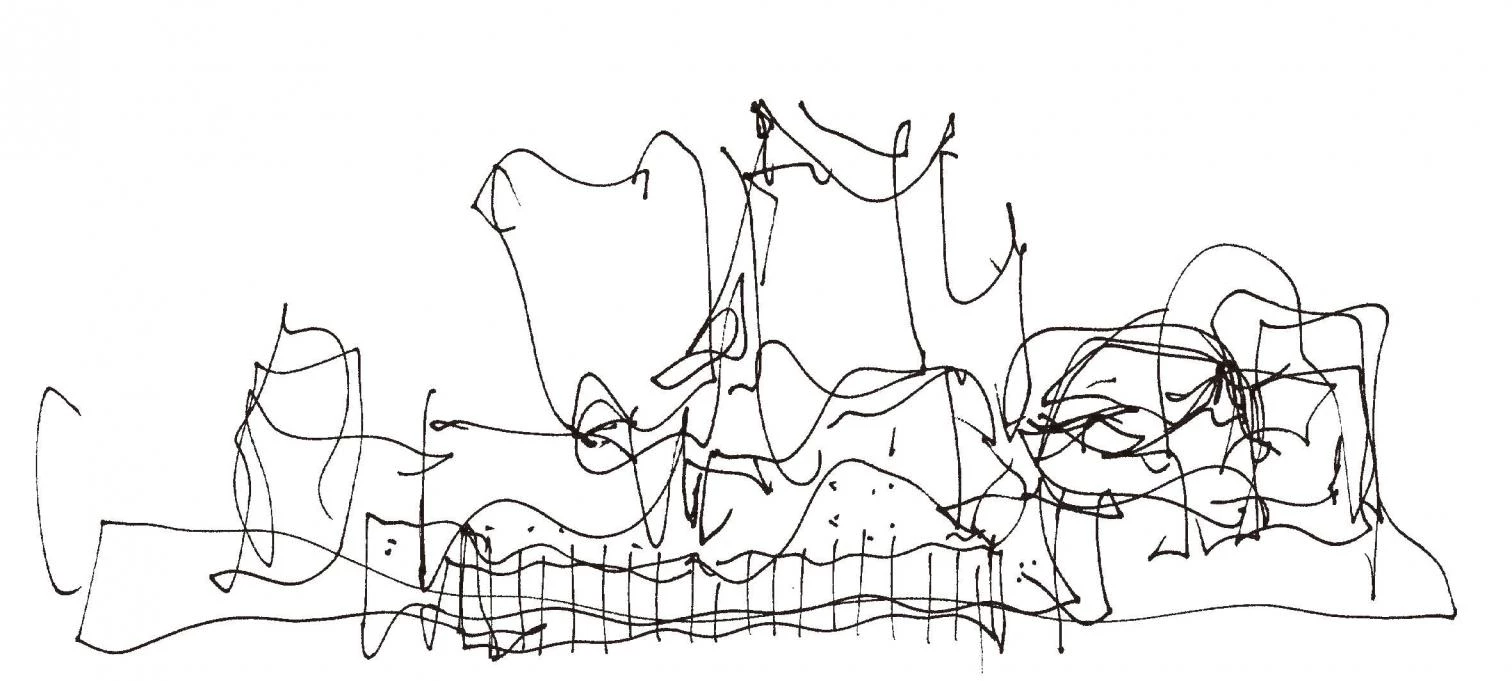

Swirled by Frank Gehry in a block of Los Angeles downtown, the stainless steel-clad volumes of the long awaited Disney Hall house magnificent spaces of Baroque inspiration and an expressionist, stepped concert hall.

Initially meant for another site and another architect, the Tenerife concert hall was entrusted to Calatrava in 1988, already in its definitive location by the sea. From the very first project to the finished work, carried out at a cost of 72 million euros, it maintained its characteristic logotype profile, with the colossal folded wave rising weightlessly over the almond of the concert hall. Fabricated in steel with shipbuilding techniques and by shipyard workers, the metal wave is clad in a way that feigns continuity with the white concrete and trencadís that give the complex a visual homegeneity, and it has no other function but a symbolical one, a bit in the manner of the Arch of Saint Louis, the most dia-grammatic work of a Saarinen whose early death cut short a trajectory now curiously being pro-longed by Calatrava. And just as the modeling of the exterior volumes stubbornly refers to his initial sculptural renderings, so does the beautiful hall ac-commodate its 1,660 seats beneath the converging aerial palm leaves of many a previous project, and before a canopy that folds with the same musical articulation of his early work, the doors of the Ernsting warehouses, insistently illustrating the architect’s fidelity to his formal universe.

Ecstasy and Hyperbole

Quite different is the case of the Walt Disney Concert Hall, erected in downtown Los Angeles with the$50 million donated in 1987 by the widow of the cartoonist and motion-picture producer, commissioned in 1988 to the Californian Frank Gehry after a competition that brought him face to face with three European winners of the Pritzker Prize, namely James Stirling, Hans Hollein, and Gottfried Böhm, and completed at a final cost of $274 million in accordance with a project that is nowhere near the original one, which contained a hall much resembling Berlin’s Philharmonie but with a huge greenhouse for a foyer. The WDCH, as built today, uses for its main hall the rectangular floor plan preferred by acoustic experts, but here this is dissimulated by slanting curves, enriched spatially by the placing of its 2,260 camouflage-upholstered seats in a hyperbolical barge with terraces à la Scharoun, crowned by a ceiling of wooden strips that form a canopy of resonant clouds, and presided by an explosive organ that sheaves sharply edged stalks with Wagnerian violence. The complex dominated by the extraordinary performance hall unfolds under a shaken cover of warped surfaces of stainless steel and over a plinth of sandstone and travertine, and the theatrical interiors combine geometrical trees of pop sensibility and corridors that wind in the manner or Serra’s Torqued Ellipses, with a Trustees Room shaped like a tormented cone that leads to an ecstasy that is more exhausting than Borrominian. Apart from interruptions caused by a variety of difficulties (the economic decline of the early nineties, the street riots of 1992, the devastating earthquake of 1994), between the initial project and the final version is Gehry’s winning of the Pritzker Prize in 1989, with the attendant growth of his office, the use from 1991 of the CATIA computer program, that enabled him to build previously inconceivable forms, and the realization between the years 1992 and 1997 of the Guggenheim Bilbao Museum, a work if not for which the Walt Disney Concert Hall would hardly have come to pass.

Despite evident connections, critical reception of the two auditorium has not been equal. At 74, Gehry is still much admired, and commentaries on his Disney Hall choose to overlook its being a Guggenheim in encore (even the stone cladding envisioned at the start turned to metal in the wake of the Bilbao success), excuse the spectacle aspirations expressed by its proximity to the dream factory that Hollywood is, and reach dithyrambic levels in cases like Martin Filler, who in The New York Review of Books declares this work superior to the Bilbao museum, names the Californian the great Gesamtkunstwerker of our times, and opines that he must from now on be compared only to the greatest masters of the past, from Brunelleschi and Alberti onward, without forgetting the builders of the Gothic cathedrals. In contrast Calatrava, 22 years Gehry’s junior, is still short of obtaining the collective backing of his colleagues, who cringe when some fan of his likens him to Michelangelo or Gaudí, refuse to accept his works as logos for Valencia, Milwaukee or the Athens Olympics, and take on lambasting tones in cases like Deyan Sudjic, who in the same Domus issue that devotes cover and 24 pages to Disney Hall assesses the reputation of the “omnipresent Santiago Calatrava” in two pages that write off the Valencian as a kitsch populist whose rhetorical humility is hardly in keeping with the megalomaniac scale of his works.

Nonetheless, the critics of one and the critics of the other use the same terminology: cathedral or Stadtkrone, sculptural or scenographic, populist or pop. Courtesy of Oldenburg, in front of Disney Hall will rise an enormous neck and bow tie, a wink to Mickey Mouse that recalls Jeff Koons’Puppy in the Guggenheim Bilbao and which would not have been forgiven had it been placed in front of a Calatrava building. But it is not easy to avoid childish spectacle in times that have seen a US president dressed as Top Gun on an aircraft carrier or bishops doing the wave for the Pope, nor can one easily elude media imagery when big screen superheroes get to become governors and princes marry newscasters.