Waiting for Corelli

The mannerist virtuosity of the latest architecture, illustrated by two recent American buildings, is so excessive that it seems to call for a ‘return to order’.

In the 17th century, Arcangelo Corelli rescued music from the arbitrary contrasts and surprise effects of the stylus phantasticus. In the 21st century, after the scenographic excesses of a ‘fantastic style’ that mixes science fiction with animation, architecture needs a Corelli to carry out a return to order and restraint. The preaching of the virtues of balance and simplicity in a world of noise and spectacle, where only those who yell loudest are heard, can be dismissed as useless, hopeless nostalgic lament. But the pendular, cyclical nature of taste justifies the conjecture that we may be at the finish line of a period. In truth one is nowadays not likely to win a competition with a ‘quiet’ project, not at a time when deadened pupils demand extreme stimuli and the ever higher surprise threshold makes it necessary to be constantly raising the extravagance bar. But neither is it easy to imagine how much we have yet to see of the ongoing virtuosity that is as admirable as it is tiresome: the two buildings recently completed by the Californians Thom Mayne and Frank Gehry show just how far we have gone on this road of impact and adventure.

The mannerist virtuosity of the latest architecture, illustrated by two recent American buildings, is so excessive that it seems to call for a ‘return to order’.

In the late 80s, the restaurant Kate Mantilini was the hangout of Los Angeles architects. Designed by Morphosis, it summed up with abstract violence the constructive conflict and geometric provocation of the California school of which Frank Gehry was master and patron. Fifteen years later, Thom Mayne remains at the head of the firm (his then partner Michael Rotondi left it to concentrate on SCI-Arc, the experimental school of architecture they founded together), but as The New York Times points out with questioning astonishment, the tormented enragé of those years has become “the government’s favorite architect,” and his baroque and catastrophic language has moved on from restaurants to major public projects. Morphosis has won two important competitions in New York: for the Olympic Village in Queens, which will go up even though the city has lost its bid to host the 2012 Games, and for Cooper Union’s art and engineering Building. Going up right now are three works falling under the ‘design excellence’ program of the General Services Administration: a federal office building in San Francisco, a courthouse in the state of Oregon, and a satellite control station near Washington, D.C. And just finished in Los Angeles are three projects that have been receiving unanimous praise: two large public schools on one hand, and on the other hand the colossal Caltrans District 7 Headquarters of California’s transport department, whose thirteen stories, lined with origami-like aluminum, rise in the very same downtown area where Rafael Moneo inaugurated the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels in 2002 and Frank Gehry the Walt Disney Concert Hall in 2003.

The Caltrans building by Morphosis accommodates offices for the California transport department in an aluminum-clad prism, with huge signs and tight neon lights that evoke the billboards and car tail lights of busy freeways.

Conceived with technical self-confidence and graphic clarity to evoke the billboard-flanked freeways that are drawn up and administered in it, the building expresses its run over faith in the future and its speedy optimism with the same resources that the Russian constructivists used: exposed scaffoldings, diagonal signage, acrobatic flights, and such. The whole thing is wrapped with a perforated metal skin that spills in folds to form canopies, and is scarified with decorative hyphens or mechanical eyelids that open up at twilight. It is then that one can best perceive its being a built metaphor of the city of billboards and freeways, because the uncertain light of this time of day gives protagonism to Motordom, the neon installation of artist Keith Sonnier, where the parallel red and blue bands crossing the exterior plaza and the urban foyer four stories high evoke the familiar image of tight freeway traffic, frozen in the colored lines of long-exposure photographs.

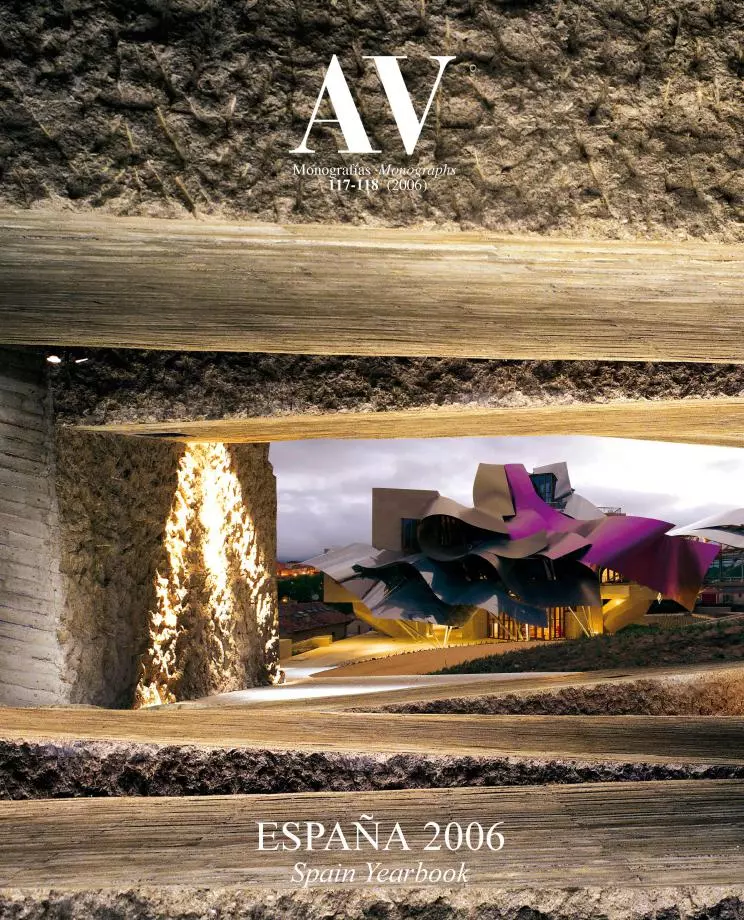

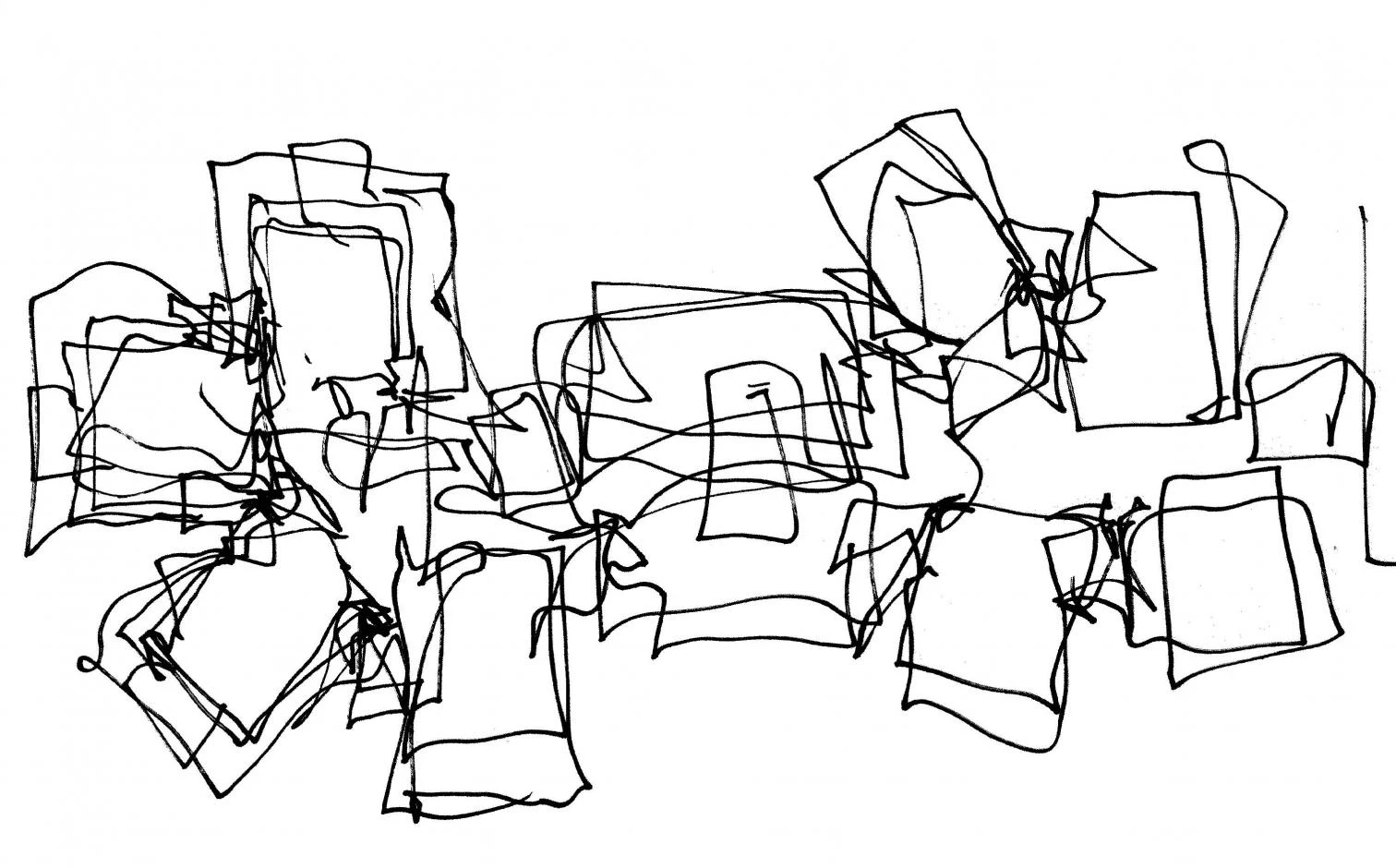

Gehry’s Stata Center orchestrates the artificial intelligence laboratories of the MIT in a theatrical container of labyrinthian complexity, with dancing forms that transform the building into a smiling, still life cartoon.

On the other side of the United States, but also designed by a Californian, Frank Gehry’s Stata Center in Cambridge is the result of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s commitment to signature architecture (very close by is Steven Holl’s controversial Simmons Hall, a student dormitory characterized by a mesh of tiny openings, aleatory perforations, and shrill colors, and elsewhere on campus are works by the likes of Charles Correa, Fumihiko Maki, and Kevin Roche). In this building, the fragmented language of the master from Santa Monica reaches paroxysmal heights. Meant to house information technology and artificial intelligence laboratories as well as the school’s philosophy and linguistics department, the vast complex of classrooms, offices and meeting rooms – connected by a labyrinth of foyers, ramps, and galleries that MIT’s free access policy turns into a spectacular and oneiric public place of encounter – consists of a multitude of volumes of different materials and colors that interlock as if Alice’s Mad Hatter had distractedly brought together the pieces of a tea set to fabricate a fun and outrageous still life.

One cannot miss the reference to animation. The crooked facades and pillars in the precarious balance of a cartoon gelatin and the symphony of colors in the interior scenography skillfully speak the Disney language, and the sequence of outlandish roof pavilions – Achilles, Buddha, the Helmet, the Giraffe, the Twins – immediately suggests a cast of characters in an animated film. But this nursery Piranesi replaces the mythical Building 20, a huge shed of anonymous make that was hurriedly erected during the Second World War for the purpose of developing the radar, and whose subsequent scientific productivity was so immense that it was nicknamed the ‘magical incubator’. It seems reasonable to wonder if technological creativity necessarily demands aesthetic innovation. MIT’s incumbent president believes that the university campus, in its homogeneity devoid of pretensions, resembles the disciplined landscape of a military base, and that the unexpected virtuosity of the signature architecture now being promoted in it can better express the institution’s adventures pursuing research and knowledge. He, to be sure, has no longing for Corelli.