Spain and its Specter

The pavilions of universal expositions provide good portraits of the countries, and those of Spain have been haunted by the ghost of Oriental exotism.

A specter is haunting Europe: the specter of identity. Under the demographic and cultural impact of the torrential flows of immigrants, and in the geopolitical context of successive enlargements of the European Union, the old nation-states of the continent anxiously undergo processes that have ren-dered their profiles blurry and the limits of their common project imprecise. With the rational foundations of enlightened citizenry by now withered, the return of the repressed takes the form of an identity foliage that vigorously sprouts from the same romantic humus that served to nourish the myth: a unanimous forest that misleads us with the penumbra of understanding and traps us with the tendrils of political correctness, in such a way that we can get through it with the knife of historical criticism, an analytical weapon that enables us to slit open the narrative fictions on which our different identities are based, and perhaps also pedagogically dissect them to expose their ideological anatomy. Since a bit over a century and a half ago, universal exhibitions have been a privileged theater for this imaginary con-struction of collective identities, and a sketchy review of their architectural pieces – so often ephemeral – can throw as much light on the mechanisms of representing political power and the instruments for the manufacture of social perception as a painstaking analysis of many monumental and permanent works. In 2000 Daniel Canogar published a graphic and literary account of Spanish pavilions in these events, and it has served as a source for much of this essay.

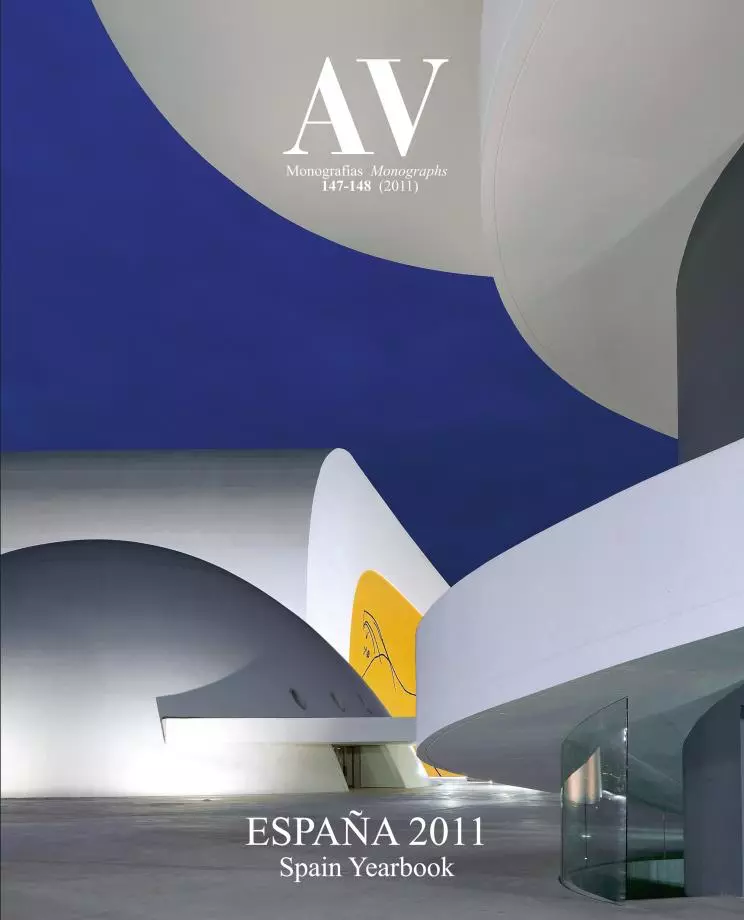

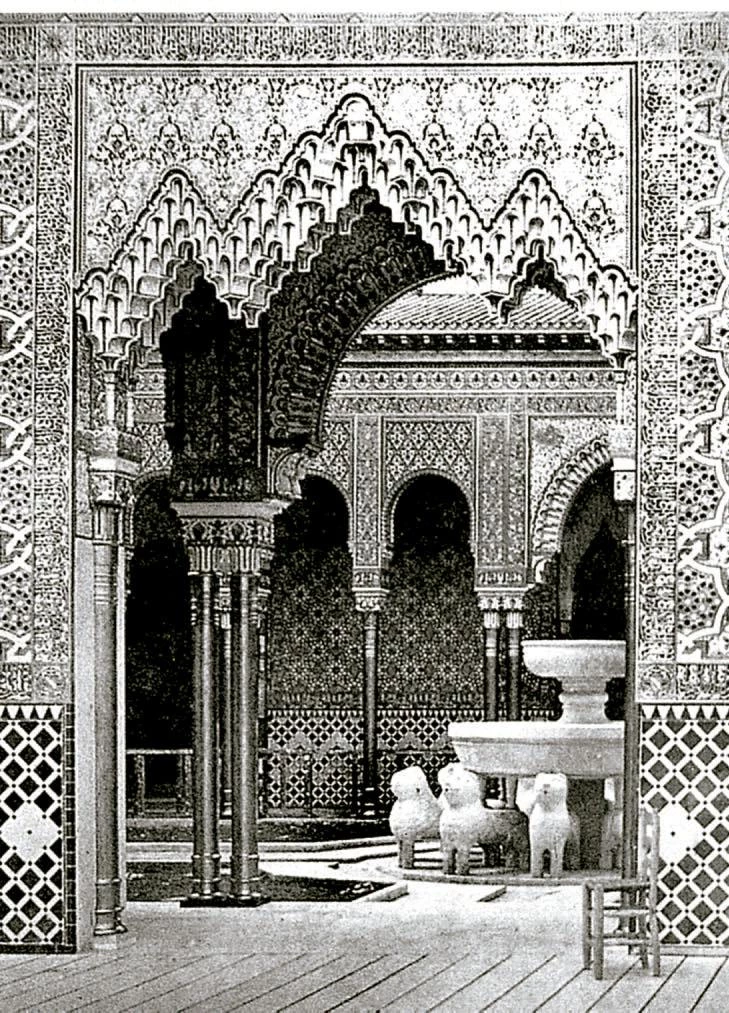

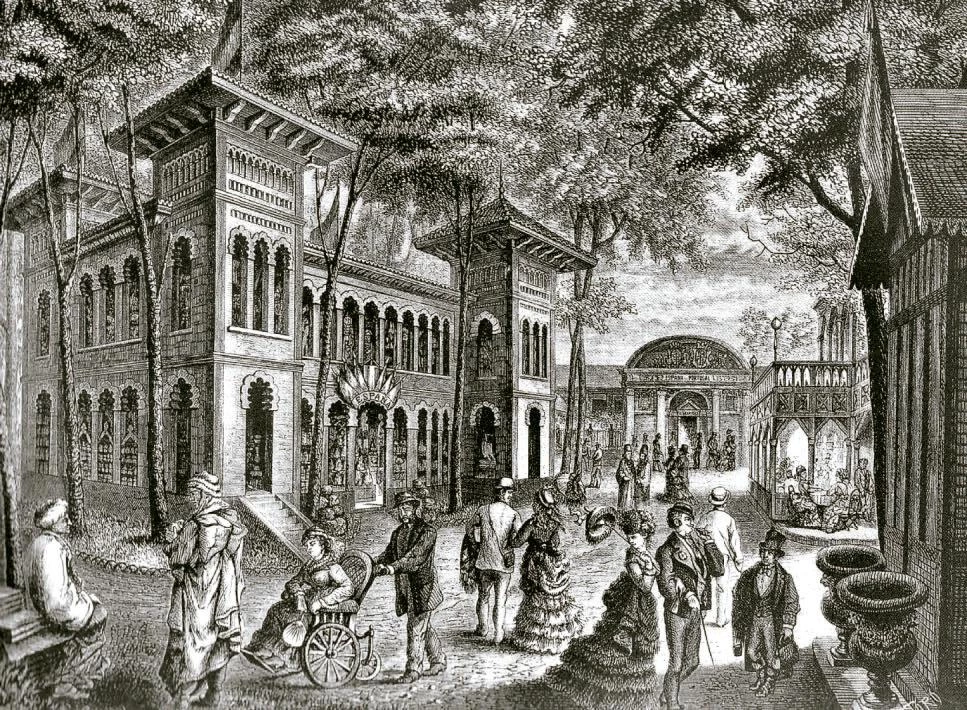

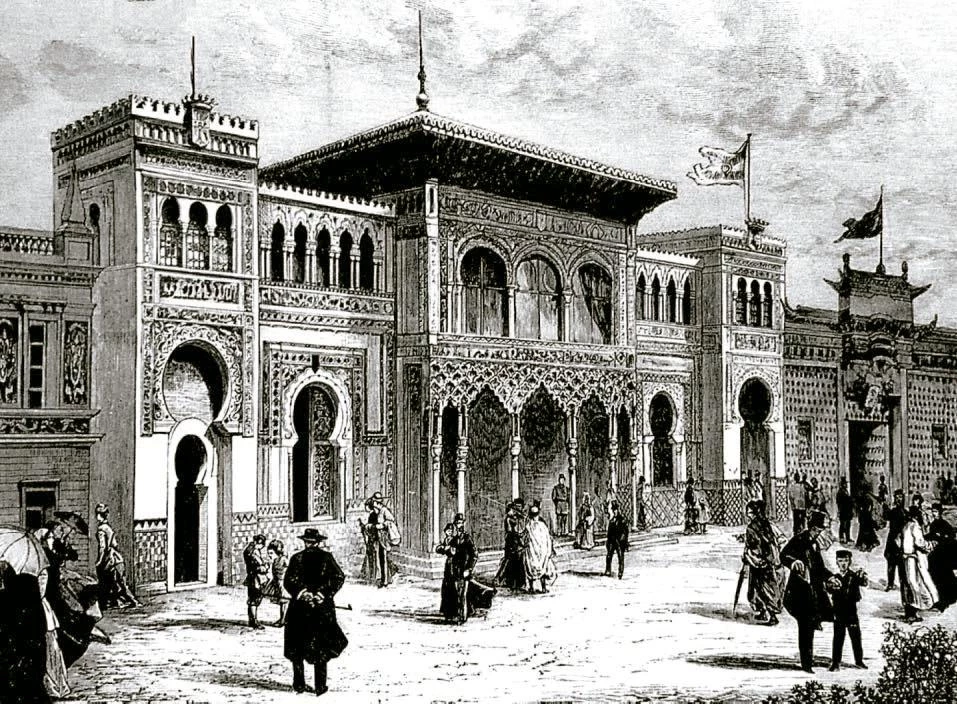

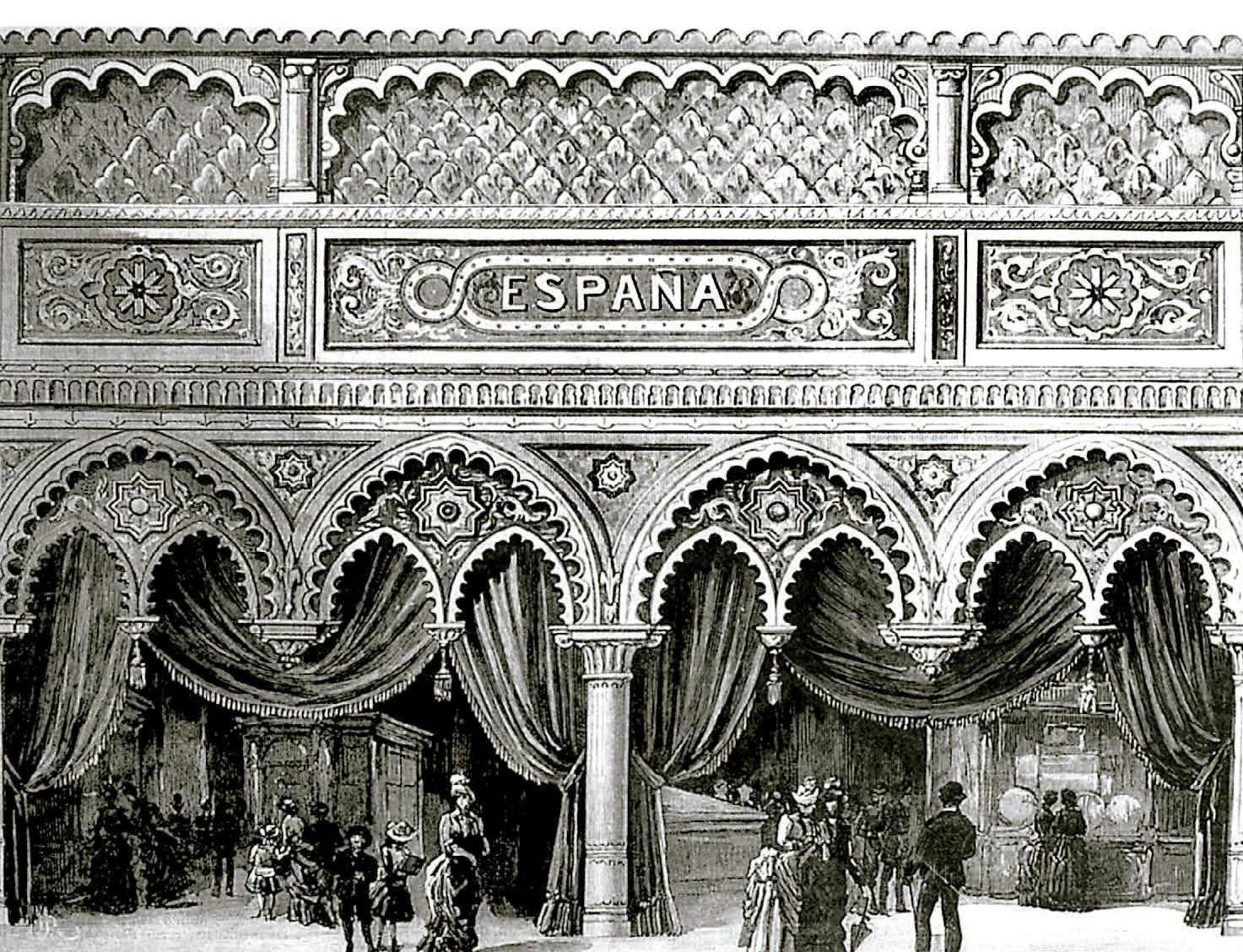

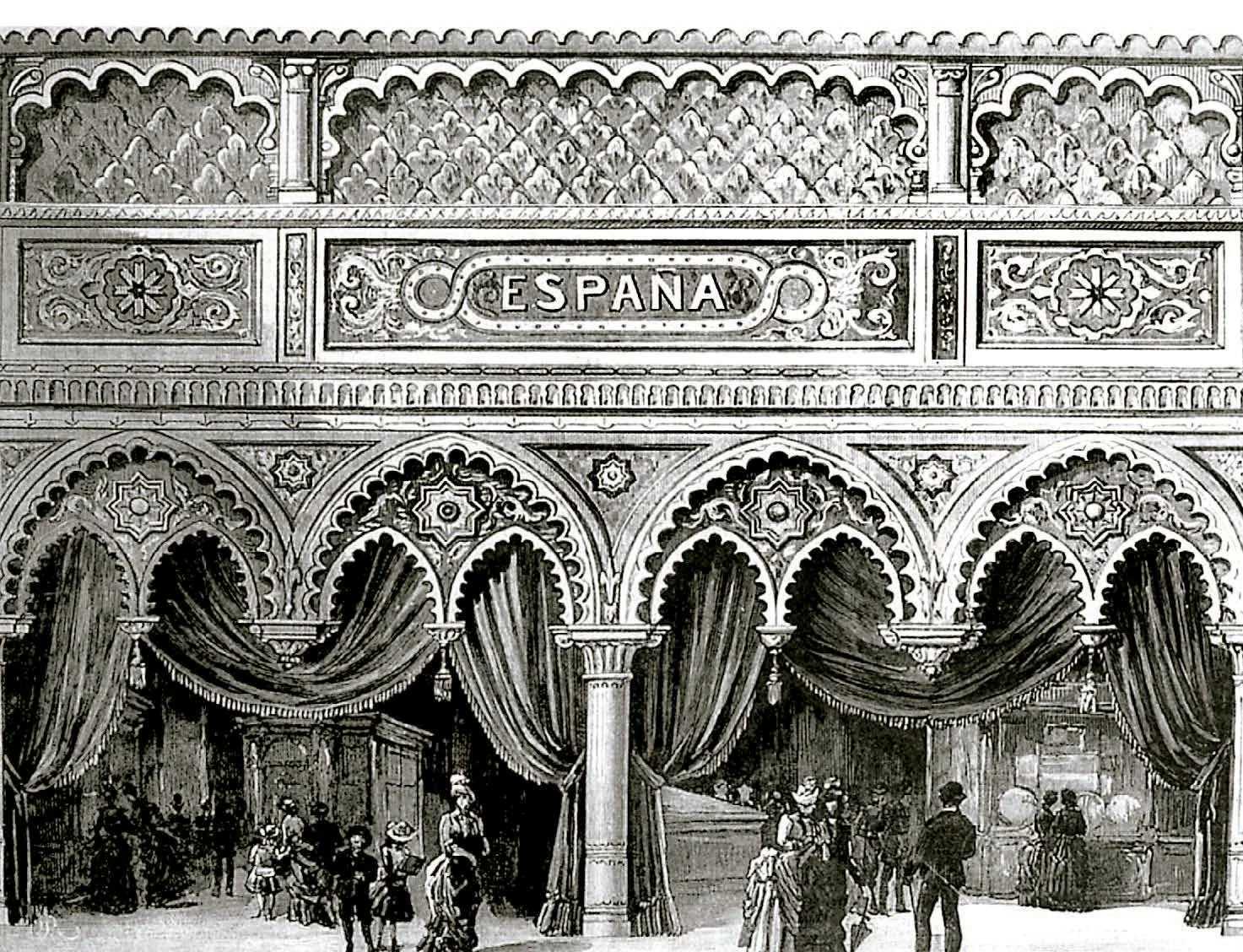

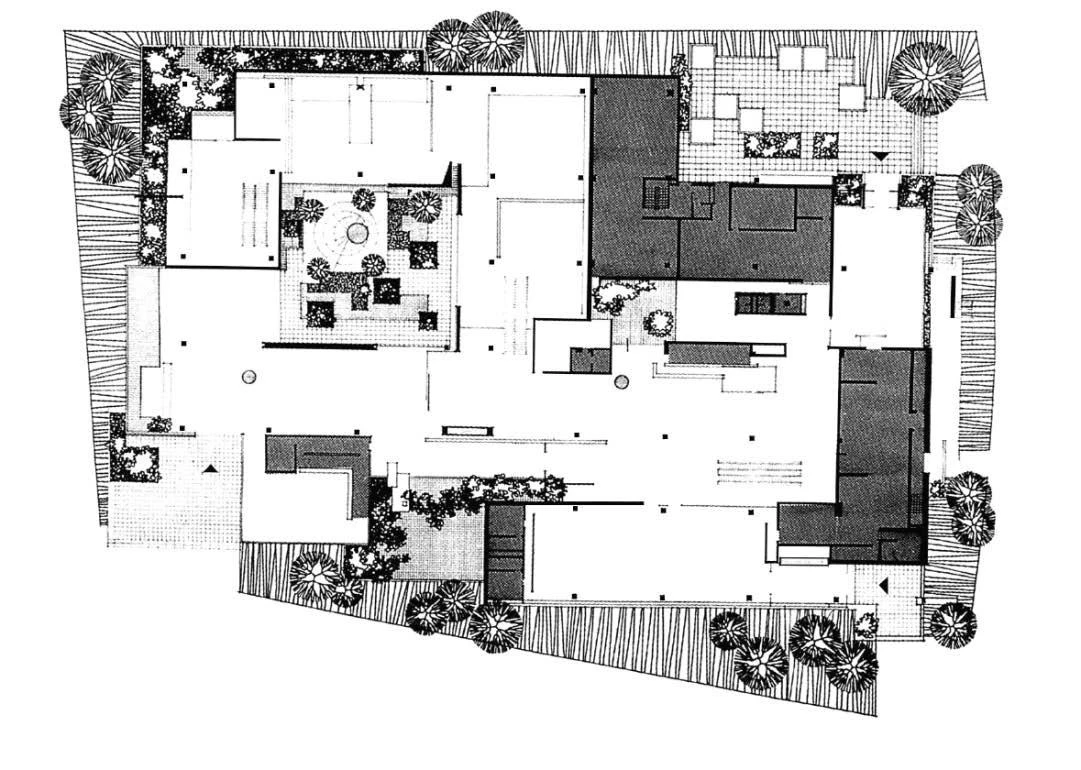

Orientalism inspires the Spanish section in Antwerp in 1885 (below), just like the replica of the Court of the Lions in the Crystal Palace or the pavilions of Spain in Vienna in 1873 and Paris in 1878 (above).

The Crystal Palace of 1851 initiated in Lon-don an architectural history where the mer-cantilistic race among colonial empires was presented within the particularly appropri-ate framework of a greenhouse – designed by Joseph Paxton, a gardener-landscapist who took inspiration from the vegetal world for the colossal light construction of iron and glass –, a building type that in the metropolis served to conserve the exotic specimens collected in their botanical expeditions, but that was also used, when first developed, to grow the lemons and oranges that prevented scurvy in the long sea voyages without which the overseas might of the great European powers is unimaginable. Spain, by then finished as a colonial power and stumbling along in its industrial development, likewise used the greenhouse when it decided to present its own international expositions a decade before losing its last remaining colo-nies, Cuba and the Philippines.

The caliphal arches in the Chicago expo of 1893 or the patio of the Alhambra recreated in the Paris expo of 1900 reflect the same fascination with Andalusia as the street in the Spanish village for the Barcelona expo of 1929.

It happened in Madrid in 1887 with the small Exposition of the Philippine Islands, which left Ricardo Velázquez Bosco’s Palacio de Cristal in Retiro Park, and in Barcelona in 1888 with the more ambitious Universal Exposition, which incorporated the Umbracle raised in the Parc de la Ciutadella by Josep Fontseré: two greenhouses for tropical plants that made one dream of the exoticism of faraway and primitive edens, in contrast with the manufactured exhibits at the Palaces of Industry or the Galleries of Machines. But while Spain looked for the exotic in the overseas ‘other’, the central nations of Europe could only see this peripheral peninsula through the romantic prism of its Arab heritage. The indus-trial products displayed by the country at the Crystal Palace – knives, guns and guitars – are embarrassing in their folklorism, and when Paxton’s work was moved from Hyde Park to a permanent site outside London, the Alhambra Court recreated by Owen Jones inside it became a milestone of the orientalist fashion that has since marked Spain’s image.

At the Paris World Exposition of 1867, the French Empire tried to go beyond the British one – which had arranged the inside of the Crystal Palace as an abbreviated reproduction of the world – with a colossal ring-shaped construction in the Field of Mars that organized the products of the planet’s two hemispheres in accordance with Diderot’s encyclopedic taxonomy. Around it, a picturesque garden served as the site of the national pavilions, among them Spain’s, built by Jerónimo de la Gándara in a neoplateresque style that many associated with the conservatism of the Isabella II period, and which went unnoticed in that fairground of attractions. Nevertheless, the First Republic saw the return of orientalism as a progressive expression – besides its sensual and playful connotations, which made it very appropriate for spectacles, from theaters and bullrings to exhibition pavilions –, and Spain was at the 1873 Vienna World Exposition with a neo-Mudéjar pavilion by Lorenzo Álvarez Capra and a neo-Arab kiosk where wines from Jerez were served: the same hom-age to Muslim heritage that would be seen in the horseshoe arches of the Spanish Pavilion at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibi-tion or in the popular neo-Mudéjar pastiche built by Agustín Ortíz de Villajos to represent Spain on the Avenue des Nations of the 1878 Paris World’s Fair, which won the gold medal following critical and public acclaim.

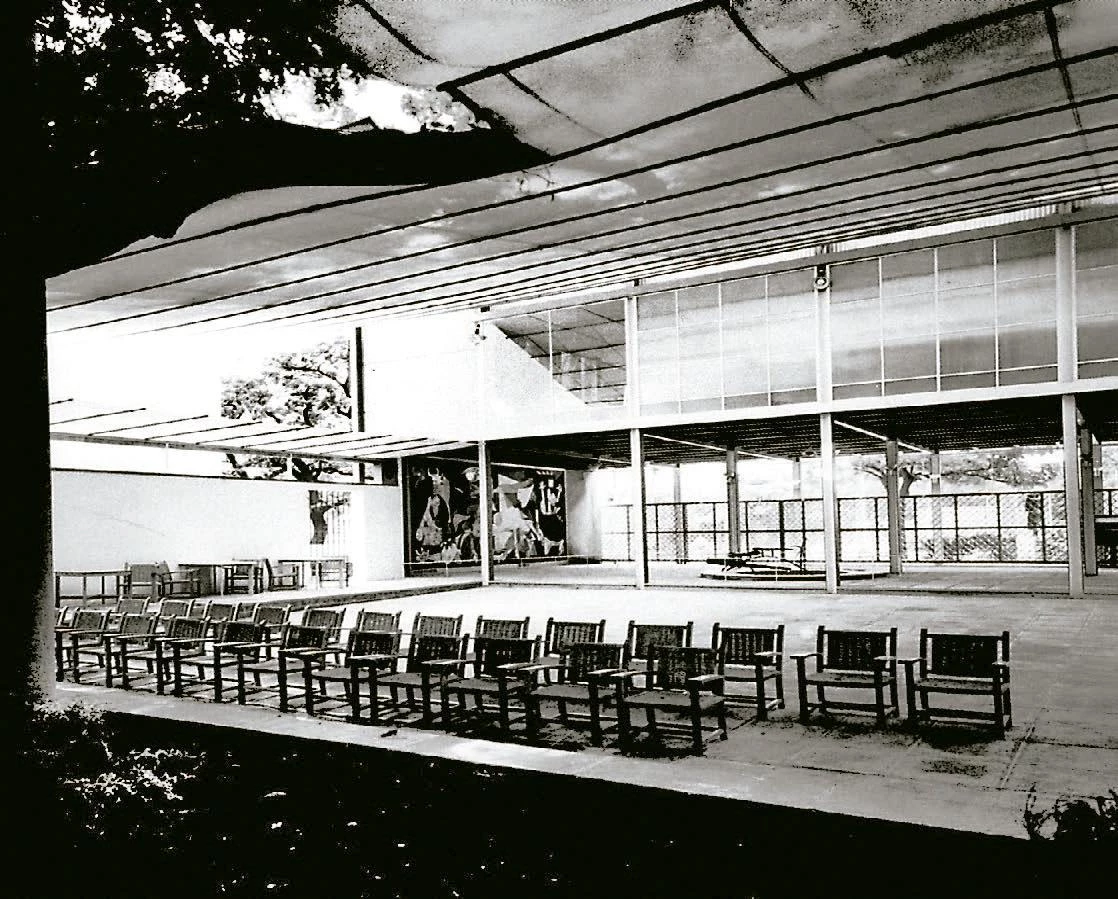

The neovernacular style of the Oil Pavilion at the Seville expo of 1929 marked a regionalist path towards the full modernity of the mythical Spanish Pavilion in the Paris expo of 1937, Corbusian with Mediterranean hues.

The neo-Arab was present in the brick and the ceramic decoration of the pavilion of the 1883 Mining Exhibition (now the Palacio de Velázquez) and the Moorish Pavilion of the 1887 Exposition of the Philippine Islands, two works by the same Velázquez Bosco who built the Palacio de Cristal, and also located in Ma-drid’s Retiro Park. It was even present in the hardly favorable framework of Catalanist his-toricist and medievalist eclecticism of the 1888 Barcelona Universal Exposition, through the exotic pavilion of the Trans-Atlantic Company that is attributed to Antoni Gaudí. And it was prominently present in the celebrated Spanish Pavilion at the great 1889 Paris Universal Exposition, designed by Arturo Mélida on the banks of the Seine like a neo-Mudéjar collage with Gothic touches, which was praised by the public for the same reasons as the colonial sec-tion on the Esplanade des Invalides – a tableau vivant featuring some 200 Asian, Oceanic, African and Arab natives –, where the fascina-tion for the primitive carnality of the ‘inferior races’ reached a climax in the belly dancing shows on ‘Cairo Street’, in the shadow of the Eiffel Tower, an extraordinary structure that expressed Europe’s technical might.

El espacio hipóstilo en la expo de Bruselas de 1958 el patio encalado con celosías en la de Nueva York de 1964 muestran una arquitectura moderna española que no excluye elementos del clima o la historia del sur peninsular.

Fleeing perhaps from the stigma of primitivist exoticism, the Spanish Pavilion at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition was built by Rafael Guastavino as a replica of the Lonja of his na-tive Valencia, but Arabism asserted itself in the Spanish section of the Manufactures Building, where Joaquín Pavía took inspiration from Córdoba’s Mosque to build a hypostyle space with over a hundred two-colored columns and two-colored arches, in tune with the oriental taste that once again triumphed with a ‘Cairo Street’ similar to the Parisian one, and all this in the context of a great exhibition that would be remembered as having popularized in the United States the Beaux-Arts eclecticism that the architects had learned in the French capital. Spain also went to Paris in 1900 to participate in the Universal Exposition of the turn of the century with a neoplateresque pavilion, built by Juan Urioste y Velada on the cluttered side of the Quai d’Orsay to stress the Castilian identity of a country that had re-cently suffered the collective trauma of 1898, and once again orientalism, discarded from official representation, came back through the porthole of colonial exhibitions, with a small city designed by the Frenchman Dernaz, ‘Andalusia in Moorish times’, which besides extras wearing djellabas, flamenco groups, gypsies and donkeys, included a 65-meter-tall Giralda tower, an Arab town quarter, and a reproduction of the Court of the Lions: the same piece of the Alhambra, incidentally, that would grace the Spanish Pavilion at the 1910 Brussels Universal Exposition, a few years after the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition mixed Moorish and Mexican in the ‘Streets of Seville’ set, entirely dedicated to entertain-ment and spectacle.

After the collapse of the Ancien Régime with World War I, the great exhibitions continued to celebrate technical progress and express the civic pride of the host cities, but the fractures of the avant-gardes and the ominous rise of totalitarianisms began to manifest themselves in these events. The 1925 Paris Decorative Arts Exposition consecrated the style known by its own name – Art Déco –, but both Melnikov’s Russian Pavilion and Le Corbusier’s L’Esprit Nouveau spoke a modern language that Spain could only timidly try to follow by moving from historicist to neo-vernacular with the regionalist pavilion by Pascual Bravo. Later, the 1929 Barcelona Universal Exposition transformed the city with its Noucentist monumentalism – an offshoot of the City Beautiful Movement that Burnham had launched in Chicago –, and exalted electricity through spectacular night illuminations that recalled the Paris of 1889 and the Chicago of 1893 but also prefigured the choreographies of light that Albert Speer designed for the Nazi rallies in Munich’s Zep-pelinfeld. In the Catalan capital, the modern milestone would be Mies van der Rohe’s Ger-man Pavilion, but the most popular attrac-tion was the collage of the ‘Spanish Village’, which four years later would be reproduced in Chicago as part of the ‘Street of Villages’, confirming the resilience of a romantic vision of Spain that the Seville Ibero-American Exposition would secure that same year, 1929, with the exuberant Andalusian regionalism of its pavilions, plazas and palaces.

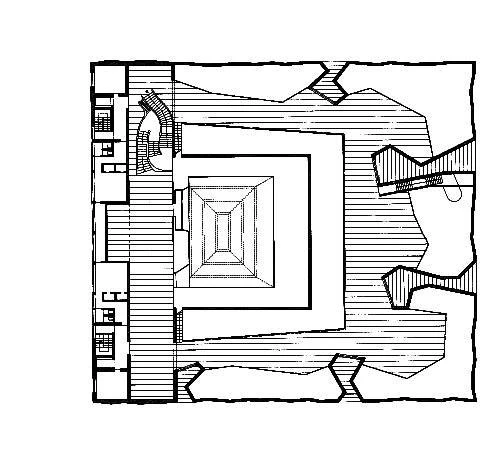

The covered courtyard in the Hannover expo of 2000 or the forest of ceramic pillars in the Zaragoza expo of 2008 are contemporary works where timeless references emphasize the symbolic content of the pavilions.

In 1937 Spain was immersed in a Civil War, and the European tensions that would lead to World War II were patent everywhere: the International Exposition dedicated to Art and Technology in Modern Life gave rise in Paris to a German and a Russian pavilion that faced one another in confrontation but aligned the Nazi and communist regimes in their use of a classicist and rhetorical kind of monumentalism, while the besieged Spanish Republic clamored for help through a Corbusian pavilion raised with laconic geometries by José Luis Sert and Luis Lacasa to showcase works like Picasso’s Guernica and Calder’s Mercury Fountain, while Julio González’s Montserrat or Alberto’s The Spanish People have a Path that Leads to a Star were in tune with the posters and publicity photographs of the facade. Paris was no party, and two years later it was a city occupied by German troops.

World War II would last six long years, and the victory of the Allies in 1945 was possible thanks to Pearl Harbor and the entrance into the conflict of the industrial power of the United States. With the 1939 New York World’s Fair, which was to contribute Alvar Aalto’s Finnish Pavilion to the history of architecture, the country had demonstrated a confidence in its own strength that would be sealed by the military triumph. But both the horrors of the Holocaust – executed by the institutions ofan exceptionally cultured and technologically advanced nation – and the shock of Hiroshima and Nagasaki destroyed the naive confidence in technical progress that the universal expositions had nourished, and the reconstruction efforts of a devastated world postponed further events of this nature for a long time.

Only in 1958 did Europe muster the energy to put into action another Universal Exposition, and the city selected was Brussels, future capital of an economic and political union that endeavored to prevent conflicts of the kind that had bled the continent. Maybe inevitably, the exhibition would unfold in the shadow of the Atomium, a colossal sculpture reproducing an iron molecule, the postwar period having been presided over by the atom, a source of pacific applications but above all the origin of the nuclear terror that kept the Cold War between the capitalist and socialist blocs frozen. The most memorable construction was perhaps the Philips pavilion, carried out with hyperbolic paraboloids by Le Corbusier and Iannis Xenakis to accommodate the ‘Electronic Poem’ created by the French-Swiss master and the musician Edgar Varese. For its part, Spain participated with a pavilion of hexagonal metallic umbrellas designed by Corrales & Molezún, an inventive structure with organic roots – in tune with the contemporary revision of modernity’s reductive dogmas – whose interior hypostyle space recalled as much the orderly labyrinth of the Mezquita of Córdoba as Frank Lloyd Wright’s Johnson Wax.

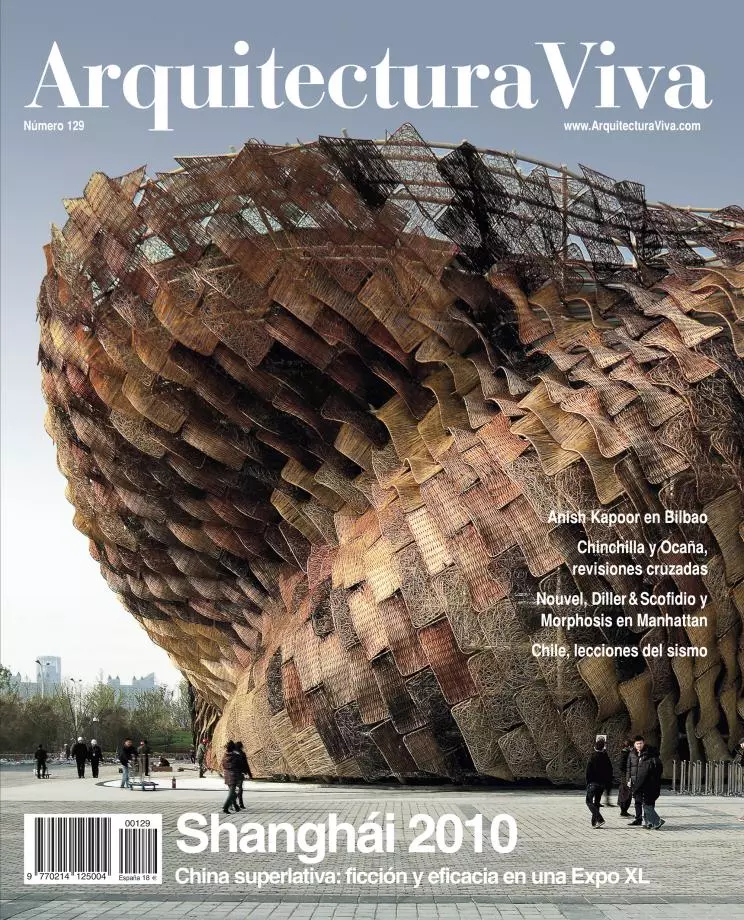

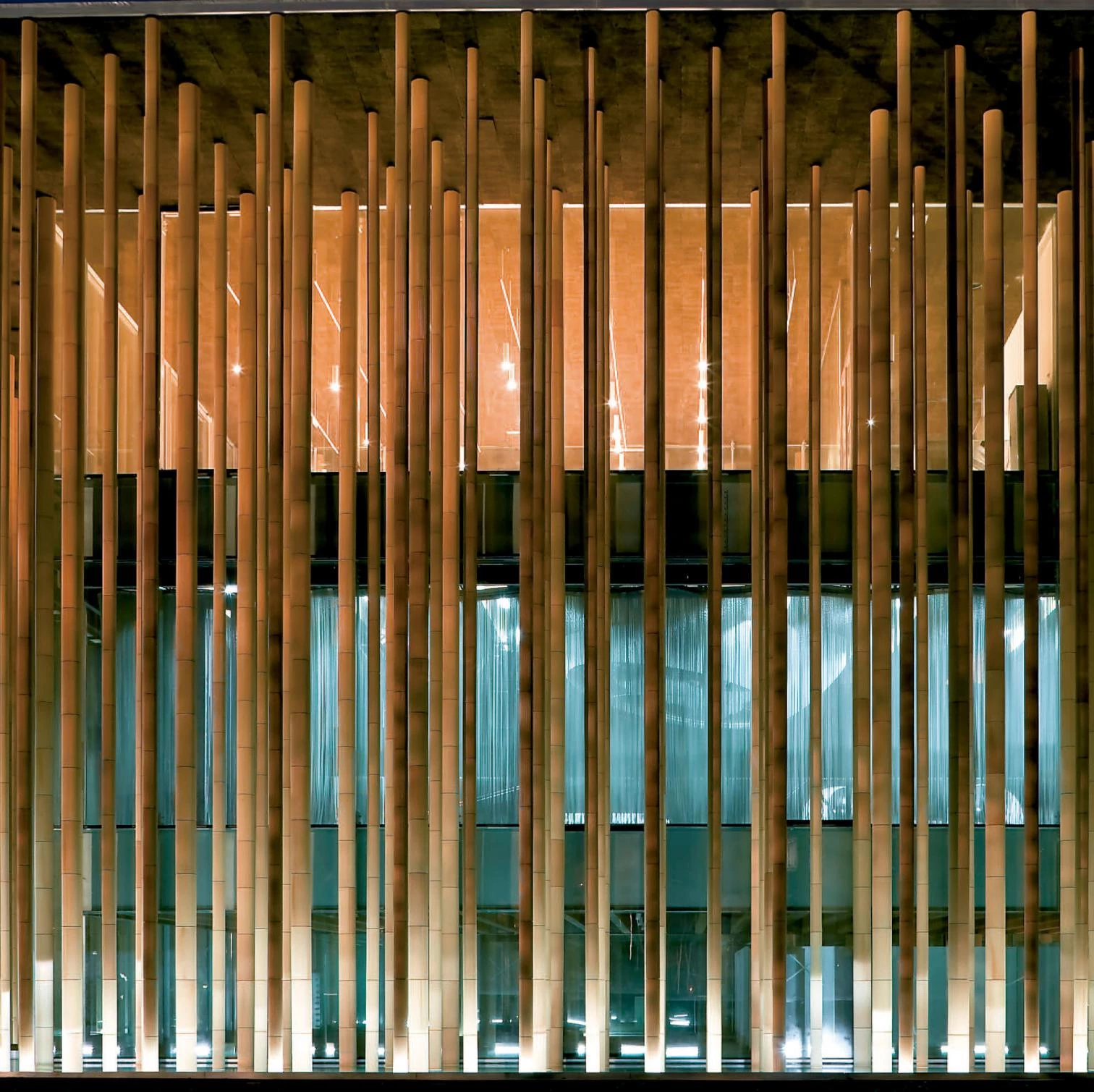

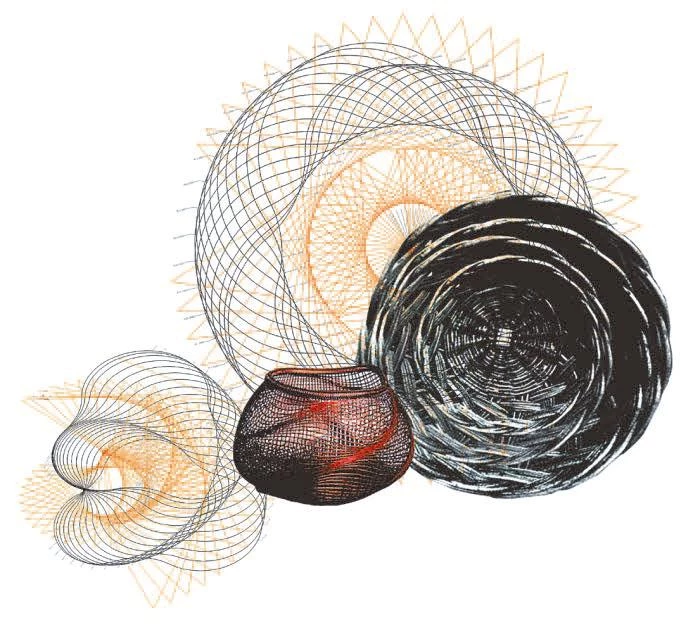

Material played a key role in the Spanish pavilion of Aichi in 2005, where the ceramic evokes Mudejar ornament; and in that of Shanghai in 2010, where the wickers recall folk basketry and sway gently like a flamenco dress.

The 1960s were American, marked by the 1962 Seattle World’s Fair and its Space Needle, which alluded to the then embryonic conquest of space, with the race for supremacy between Russians and Americans acting as a technological expression of the Cold War; the 1964 New York World’s Fair, a spectacular event protagonized by the big corporations, pop aesthetics and Disney’s animatron robots, where the Spanish Pavilion – built by Javier Carvajal as a sober concrete structure surrounding a courtyard with lattices which offered an oasis of southern serenity in the crowded confusion of the Expo – was as praised by architects as it was ignored by the public; and the 1970 Montreal World’s Fair, characterized by the modular residential utopia of Moshe Safdie’s Habitat, the tensed canvases of Frei Otto’s German Pavilion, and the great geodesic sphere of the United States Pavilion with which Buckminster Fuller depicted the fusion of the technological dream and the planetary conscience of the ‘flower power’ generation, at once critical and alternative; a futuristic and oneiric perfume that would also impregnate the Expo of Osaka in 1970 through the megastructures of the Metabolists, pneu-matic architectures and a desire for demate rialization that very well expressed the virtual reality obtained by IMAX projection systems.

Spain was not present in Montreal and Osaka, but after a long parenthesis of minor expositions, it would have its big turn in 1992, an annus mirabilis that would see Barcelona host the Olympic Games and bring to Seville a forest of pavilions surrounding the laconic volumes of the host country’s, designed by the studio of Julio Cano Lasso as a rationalist translation with marble and canopies of the courtyards and the water of Nasrid architecture. The event also equipped the Andalusian capital with several bridges over the Guadalquivir – including one by Santiago Calatrava, the same architect-engineer who would build the iconic Oriente Station for Lis-bon’s Expo ’98 – and an excellent station for the high-speed train line, designed by Cruz & Ortiz, the same team that in 2000 would raise the Spanish Pavilion at the Hannover World Exposition. There, a fractured exterior of cork concealed a placid and elegant covered court, a scheme less exhibitionistic than the stacked landscapes of MVRDV’s Dutch pavilion and less extreme than the exquisite labyrinth of music and wood of Peter Zumthor’s Swiss pavilion – in the final analysis faithful to a certain tradition of luminous and hermetic exhibition constructions that bind Spain’s image to the discreet interiors of Andalusian or Muslim architecture.

In subsequent expos – Aichi 2005, Zaragoza 2008, Shanghai 2010 – the job of representing the country has been entrusted to the expressive force of materials: in Japan, Alejandro Zaera used polychrome ceramic to build irregular hexagon enclosures that on a festive note went back to Mudéjar ornamentation and southern lattices; in the Aragonese capital, Francisco Mangado created a ceramic forest over a sheet of water that recalled the hypostyle spaces and underground cisterns of caliphal architecture, transformed now into ponds in penumbra that serve to reinforce the building’s bioclimatic intentions; and in China, Benedetta Tagliabue resorted to wicker to weave undulating volumes that pay tribute to ancestral basket-making while providing a friendly and playful icon, an ephemeral and cheerful Guggenheim that shakes its perimeter with the sensuous fluttering of a flamenco dancer, the persistent specter that makes Spain inseparable from the shadow on the wall of our deep south.