The Gulf

A New Urban Order

The Gulf is the current frontline of rampant modernization: a feverish production of urban substance, on sites where nomads roamed unmolested only half a century ago.

The Gulf – its initial development triggered by the discovery of oil – is undergoing hyper-development to ready for oil’s imminent depletion.

The Gulf is in construction now. This means its development is, inevitably, based on the repertoire of current urban prototypes – community (themed & gated), hotel (themed), skyscraper (tallest), shopping center (largest), airport (doubled) –cemented together by Public Space, extended soon with boutique hotel and museum franchise.

In its current state, the Gulf is a landscape of vast means and ambition translated with gargantuan effort that has ambiguous and sometimes disappointing results; a kind of farewell performance of an ‘Urban’ that has become dysfunctional through sheer age and lack of invention.

But for that very reason – call it historical inevitability or sheer coincidence of timing – the Gulf will be the terrain where the current crisis of the metropolis has to be confronted. The limitations of the current architectural repertoire are so blatant, comprehensive and destructive that it has become unthinkable to rely on them as a toolbox.

Eventually, the Gulf will reinvent the public and the private: the potential of infrastructure to promote the whole rather than favor fragmentation; the use and abuse of landscape – golf or the environment?; the coexistence of many cultures in a new authenticity rather than a Western Modernist default; experiences instead of Experience™ – city or resort?

The world is running out of places where it can start over. We live in an era of completions, not new beginnings.

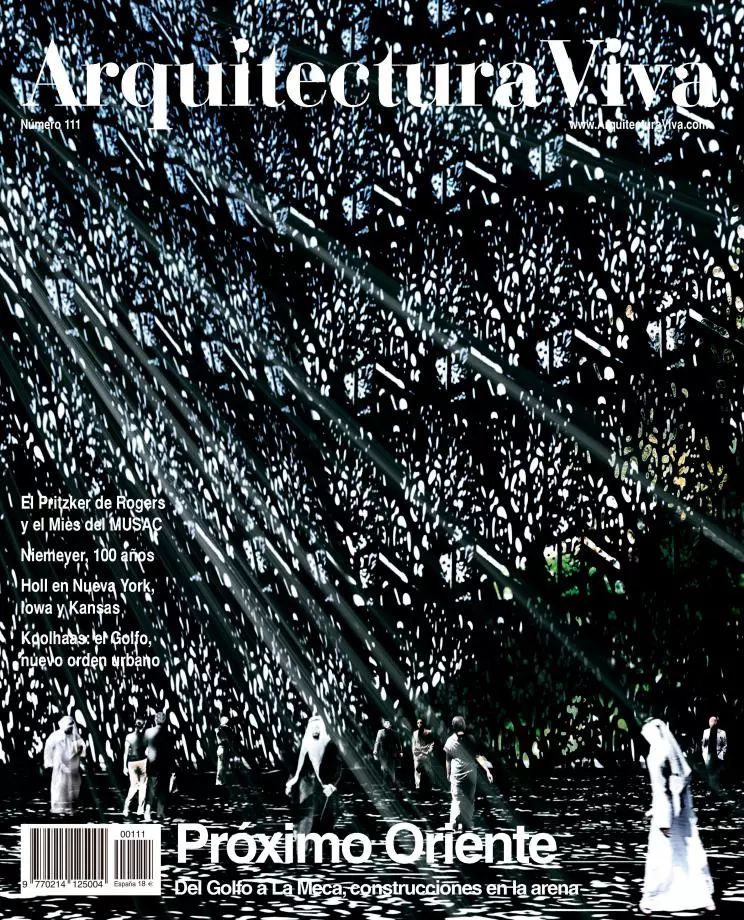

Sand and sea along the Persian Gulf, like an untainted canvas, provide the final tabula rasa on which new identities can be inscribed: palms, world maps, cultural capitals and financial centers.

The West suffers from a double neglect toward this land of opportunity: a refusal to take seriously something actually originating in the West and, subsequently, an inability to detect a rising global phenomenon.

Recent Gulf developments, much like Singapore and China in the 1980s and 90s, have been met with derision: “Las Vegas in Arabia” (Brown Journal of World Affairs), “Lawrence of suburbia” (Forbes), “a bubble built on debt” (Time), “skyline on crack” (Vanity Fair), and – most damning – “Walt Disney meets Albert Speer” (Mike Davis), echoing the condemnation fifteen years ago of Singapore as “Disneyland with the death penalty” (William Gibson). The recycling of the Disney fatwa says more about a stagnation of the Western critical imagination than it does about the Gulf cities.

To be a critic today is to regret the exportation of ideas you have failed to confront on your own beat, from your own backyard. Ironically, the vast majority of developments these critics deplore have originated and become the norm in their own countries. Is it possible to view the Gulf’s ongoing transformation on its own terms? As an extraordinary attempt to change the fate of an entire region?

The Gulf, however, is not just reconfiguring itself; it’s reconfiguring the world. Each of these Gulf cities has been synthesizing versions of the 21st century metropolis and now exports its own versions on an equally colossal scale to parts of the world modernity has not reached so far –from Morocco to Thailand.

This burgeoning campaign to export a new kind of urbanism – to places immune to or ignored by previous missions of modernism – may be the final opportunity to chart a new blueprint for urbanism. Will architecture grasp this last chance?