Countryside is the future

Koolhaas on the Countryside

The modern world is preoccupied with cities. More than half of mankind is now urban, which has been the pretext for an almost exclusive focus on the city. They are seen as the engines of economy, of emancipation, of the ultimate ‘lifestyle’. Since Delirious New York (1978), I have probably been associated as much as anyone with this concentration on the city, on the metropolis, on urbanism.

But in 2018 I will be researching everything that is not the city to prepare an exhibition in a major (spiral-shaped) venue in Manhattan. Today there is an almost complete lack of exploration of the countryside. Yet if you look carefully, the countryside is changing much more rapidly and radically than the ‘city’, which in many ways remains an ancient form of coexistence.

I first realised this in a Swiss village in the Engadin, which I visited often over the past 25 years. I began to notice drastic changes there. The village was simultaneously growing and hollowing out. A man I assumed was a farmer turned out to be a dissatisfied nuclear scientist from Frankfurt. Cows disappeared, along with their smell, and in came minimalist renovations, abundant cushions absorbing their new owners’ urban angst. Farming itself was now left to Sri Lankan workers. And nannies, nurses and assistants recruited in Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines were now looking after the homes, kids and pets of the virtual, one-week-a-year population who had caused the village to expand.

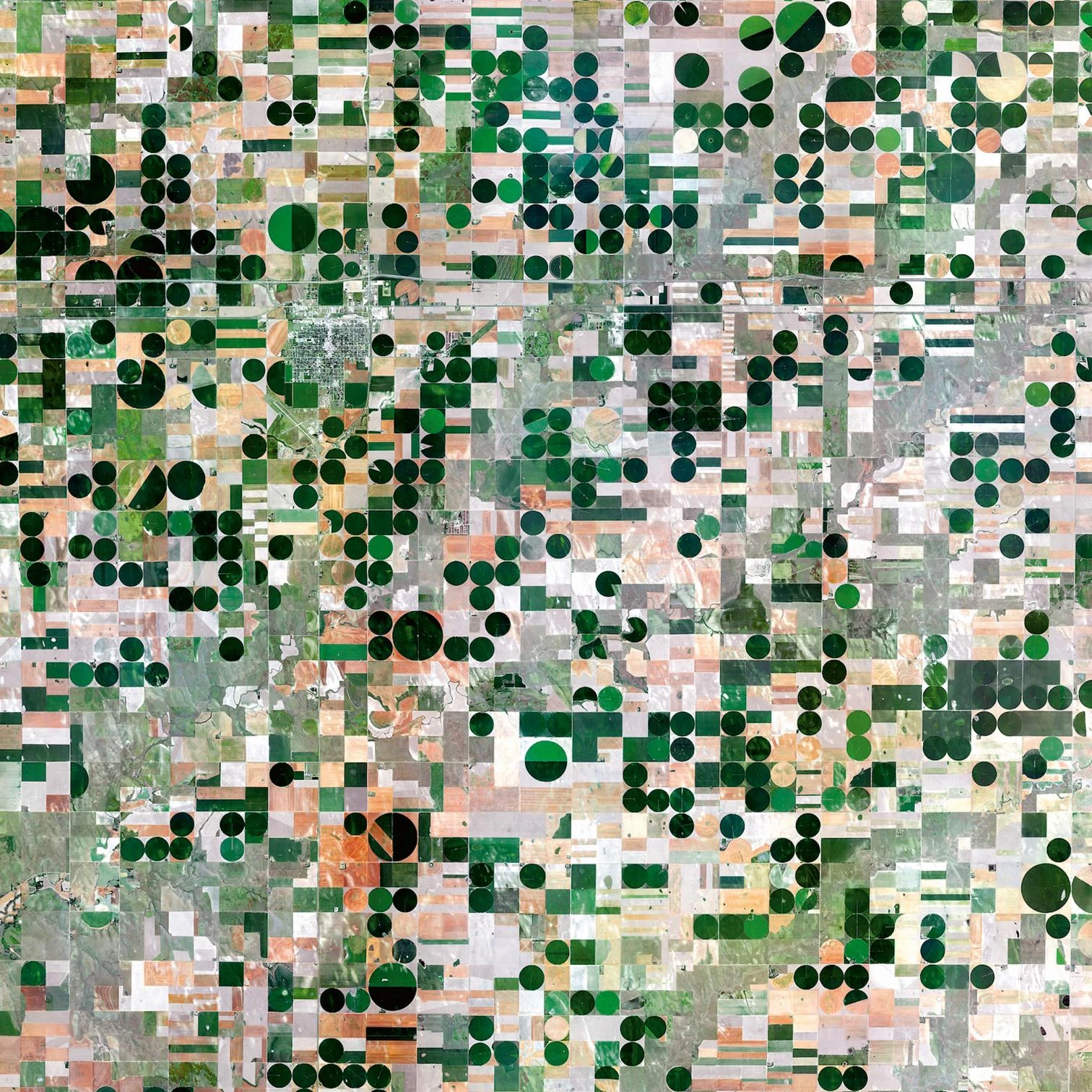

This was the trigger for a bigger exploration of the countryside globally. It has led to a realisation that, in order to feed, maintain and entertain ever-growing cities, the countryside is becoming a colossal back-of-house, organised with relentless Cartesian rigour. That system, not always pleasant, is proliferating on an unprecedented scale. The resulting transformation is radical and ubiquitous, and manifests itself in different ways around the world.

In America, for example, a zone runs through the middle of the country where satellite information has a direct impact on agriculture. Deep knowledge of every square inch of the earth is transmitted to the laptop of the farmer. The laptop is the new ground. From the laptop, the farmer feeds the data to a robotised tractor. Each season, an armada of sophisticated harvesters so big and expensive that they need to be shared and work 24 hours a day, operates almost like a military campaign, moving slowly from south to north as the temperature increases to create a linear tabula rasa, dividing America in two halves.

Russia offers a different example. With the embrace of the market economy, only a fraction of Aeroflot’s once-extensive network of air routes remains. Cities that were once connected are now condemned to return to the 19th century and have to find new purposes. The results surprised. Sometimes it has led to an increased sense of serenity: making the best of an involuntary off-grid condition, a proliferation of museums, where every provincial knick-knack is valued. Superimposed on all this is the impact of global warming: melting permafrost in the north, destroying structures and infrastructure, with new territories becoming suitable for agriculture and shifting a large area of farming to the north.

Other examples of the countryside’s transformation range from the opportunities in Germany to channel refugees to revive moribund, half-abandoned regions to the impact of Chinese railways that transform the heart of Africa. Then there are the sweeping effects of grand political redesign, not just under dictators such as Stalin and Mao but also under the European Union’s common agricultural policy. In short, for better or worse (often both) the countryside has been completely involved in modernisation, on a global scale.

Architects: Look and Learn

As an architect, I am fascinated by the physical effects of Silicon Valley’s virtual propaganda. A new scale is emerging in data centres and distribution centres. Buildings are becoming bigger and bigger, the largest so far being Tesla’s battery-making Gigafactory near Reno, Nevada. As they are increasingly automated and robotised, none of these buildings has large human populations. The human scale could become irrelevant.

In some of today’s giant greenhouses light is not admitted for the pleasure of humans but reduced to that narrow part of the spectrum that promotes growth in plants. It is a return to extreme functionality. Given the massive building in the countryside and the reduction of human presence, architecture can become more radical. Today, humans need the colour beige: we cannot stand stark contrast or colour intensity. In the new technological spaces, however, you get a shock of intensity. Coding is creating its own aesthetic.

We are witnessing the emergence of a new sublime. And this will have repercussions not only for architecture but also for citizens more broadly. It has a beauty that is in itself really amazing.

Originally in The World in 2018, yearbook of The Economist and Tiempo.