Nowadays drawing tends to be thought of as an artistic discipline of its own accord, but for a long time it was little more than a tool in the service of art, and it was in technology and science that drawings were considered useful and of value. The likes of Michelangelo or Raphael did not really give credit to the drawings their hands produced, keeping them hidden lest word get around that artists of their caliber were in the practice of sketching, that is, of hesitating. Yet while one was outlining the figure of Sibyll and the other drafting The School of Athens, drawings were already flooding the market, marked as they now were as the visible, objective, and thus transmissible expression of knowledge, without as a result being any less beautiful to look at than paintings.

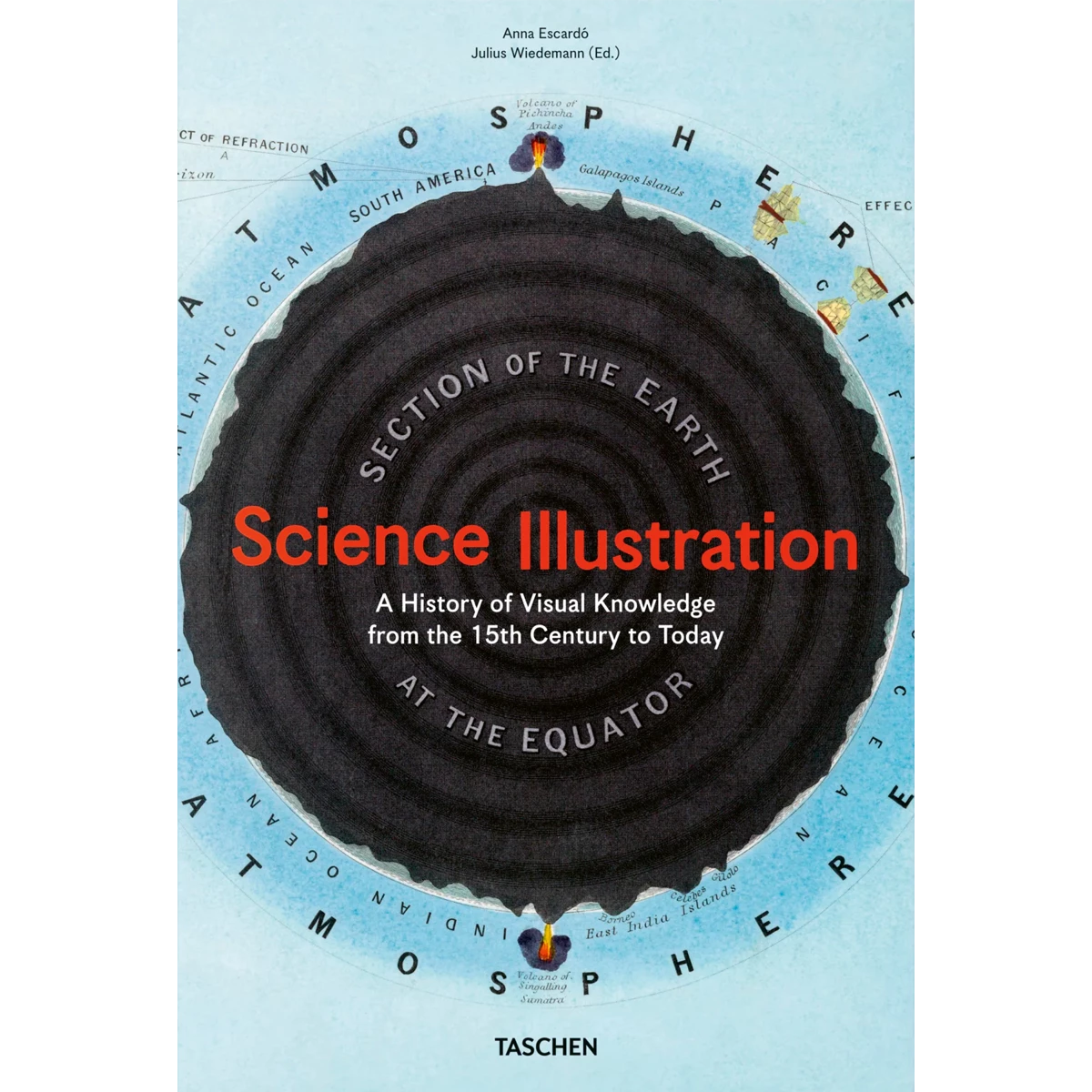

Taking stock of the cold objectivity but also the descriptive passion inherent in scientific drawings is the purpose of this monumental collection of images compiled for Taschen by Anna Escardó, and which goes from the Renaissance, when Brunelleschi made perspective a scientific tool, to this very day, when much of drawing is computer-aided and rendered by artificial intelligence.

The history recounted in 430 folio pages is that of ‘visual knowledge,’ presented through gorgeous images that result in an encyclopedia of sorts, combined with abundant texts of great precision. For the sake of clarity, it is told chronologically through the five centuries that stretch from the illustrations of the treatises of Copernicus, Cardano, or Vesalius to the depiction of the guts of the first computer or the double helix of DNA, from the earliest printed maps of America or the first drawing of the Moon seen with a telescope to the disturbing figure of a black hole, and from the naive engravings of animal species according to Pliny to the recreation of the faces of our ancestors, the early primates.

A total of 250 images arranged in a time tunnel nevertheless manages to deviate from the chronological to tell other stories. One would be the variability of the themes pertaining to each period, which, prioritizing astronomy, cartography, botany, geology, and physics over other sciences, gave rise to a way of narrating that is peculiar to drawing. And the other history, by extension, would be that of the development of drawing techniques and formats, with that of the changeable character – analytical, synthetic, or synoptic – which, in accordance with their uses, the images acquire in their endeavor to convey things as diverse as the cellular structure of the eye, the convolution of the planets, the innards of a steam engine, Napoleon’s expedition to Russia, or the scaly geometry of a serpent’s skin.

Despite her encyclopedic zeal, the author has barely acknlowledged the relevance and beauty of the technical drawings of architecture, which are hugely important in giving shape to perspective and the representation of reality, but this is no reason not to recognize the worth of a book which from start to finish treats us to the spontaneous and wisdom-filled beauty of the scientific drawing.