The Rise of Populism

Brexit and Trump have marked a year in which liberal democracies have lost ground to populism and authoritarianism. The wars and failed states of the Middle East and the Maghreb combined with the vigorous demography of Sub-Saharan Africa to produce waves of migration that aggravated xenophobia in Europe, fueling protectionist movements that were reinforced by each new act of Islamist terrorism, from Nice to Berlin. The main theater of war was the quandary of Syria, where the civil conflict between Sunnis and Shias was an episode of the regional struggle between Saudi Arabia and Iran, of the national interests of Israel and Turkey, and of the geopolitical show-down between the US and Russia, and where the siege of Aleppo made the city a symbol of suffering. Meanwhile, the difficulties of the emerging countries of Latin America and the slowing down of growth in China lowered the economic temperature of the Pacific Rim, but not the risk associated with its being the scene of the battle for hegemony between the two superpowers.

All over the planet, rebellion against inequality and elites – its outlines increasingly confusing in the age of post-truth generated by social networks – coexists with scientific and technical advances that are bound to change our societies way beyond what we can imagine today, justifying the coining of the term ‘Anthropocene’ to describe the current epoch of the Quaternary Period, which is witnessing a transformation of the Earth’s crust and climate through the action of humans, the same transformation that through biotechnology, robotics, and artificial intelligence can call into question humanity’s very nature.

The refugees fleeing from dramas like that of Aleppo reached Europe through Greece, giving rise to xenophobic reactions that ignore the shared fate of humanity, which has entirely transformed the Earth’s crust.

Spain, which shares the concern about the future of the European Union – besieged, as it is, by the rise of the populisms that are stoking the fractures of the crisis, the discontent among those swept aside by globalization, and the impact of immigration –, had a year of incipient economic boom and of political impasse, with a caretaker government and political parties incapable of agreeing, while numerous cases of corruption demoralized citizens and centrifugal tensions intensified in Catalonia. Successive electoral processes showed a slight recovery of the PP – supported by Angela Merkel in the task of defending the austerity imposed on the continent’s indebted southern countries – and the sinking of the PSOE, harassed by the populists of Podemos, which led to the stepping down of its secretary-general.

In architecture, the act of contrition pro-voked by the crisis has not prevented the erec-tion of major works, but it has brought the theme of elemental construction into the great exhibi-tions and forums. The Swiss partnership Herzog & de Meuron has wrapped up an extraordinary year with the opening of the Tate extension in London and the completion of the long-awaited and controversial Elbphilharmonie in Ham-burg, two emblems that take their place beside the exact Fondazione Feltrinelli in Milan, the exquisite new building for Vitra, the delicate intervention in Colmar, or the unique residential skyscraper in New York.

In their annus mirabilis Herzog & de Meuron completed extraordinary works like the new Tate Modern, Colmar, and the Elbphilharmonie, while Bjarke Ingels opened the Serpentine Pavilion and Calatrava the Oculus.

Many other Europeans have finished important works in the US: the Norwegians of Snøhetta, the extension of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, nourished by the technological fortunes of Silicon Valley; the British David Adjaye, the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, appropriately inaugurated at the end of the mandate of the first black US president; the alternatingly admired and lambasted Spaniard Santiago Calatrava, the impressive Oculus in New York City’s Ground Zero, which gradually sutures the wounds of 9/11; and the Dane Bjarke Ingels, an innovative residential complex that is a hybrid of block and tower, which in Manhattan amounts to a morphological reverse of the metaphysical and svelte high-rise built by the Argentine Rafael Viñoly.

Europe, for its part, saw the finishing of projects as prominent as the Niarchos Foundation in Athens, a contemporary temple raised by the Italian Renzo Piano that incorporates Greece’s national Opera and Library; the restoration of the historical Fondaco dei Tedeschi in Venice, turned into a shopping mall by the Dutch Rem Koolhaas; or the levitating construction, on top of a heritage building at the port of Ant-werp, that has turned out to be a posthumous work of the Iraqi-British Zaha Hadid. Works that must be joined by Fuksas’s atmospheric ‘Cloud’ in Rome, of the same aesthetic as Coop Himmelb(l)au’s complex in Shenzhen, Toyo Ito’s opera house in Taichung, or Philippe Samyn’s EU headquarters in Brussels.

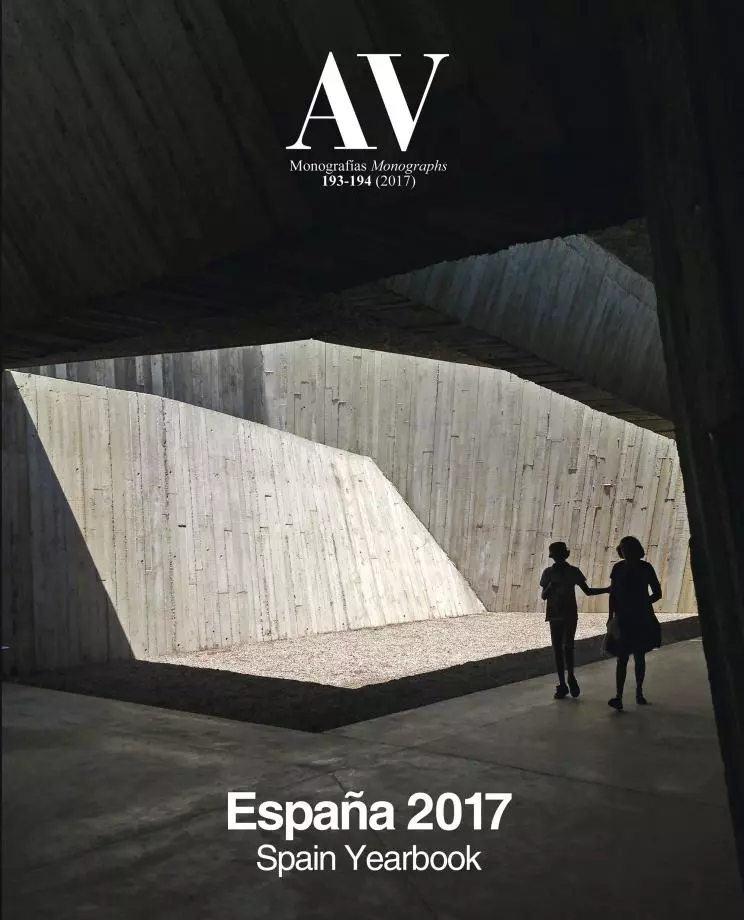

In contrast to this overwhelming collection of icons, the Pritzker Prize distinguished the career of the Chilean Alejandro Aravena, known for his social housing projects, who also directed a Venice Biennale centered on the necessary and on the inventive use of simple techniques; a message reinforced by Norman Foster’s Droneport prototype and the awarding of the Golden Lions to the Brazilian Mendes da Rocha for an exemplary career, the Paraguayan Solano Benítez for his innovative structural construction, and the Spanish Pavilion in recognition of an architecture that does not forgo quality in the context of austerity.

The Venetian biennale of Aravena gave the Golden Lion to the Spanish pavilion, the Pamplona congress debated on the change of climate in architecture and in the planet, and Foster won the Prado competition.

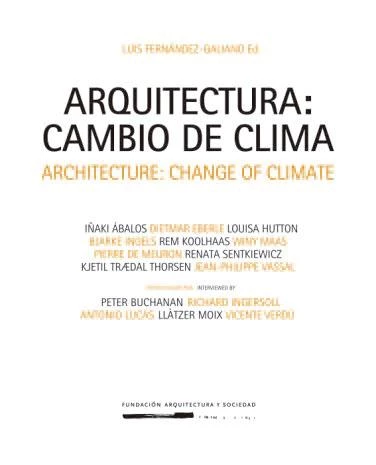

In Spain, inspired by the same purposes, the Fundación Arquitectura y Sociedad held its fourth international congress, having since the first cycle, in 2010, invited to Pamplona ten Pritzker laureates alongside alternative architects like Francis Kéré, Anna Heringer, or Benítez and Aravena themselves, to discuss the change of climate that the profession urgently needs, an objective which this time around gathered figures like Koolhaas, De Meuron, Vassal, Maas, or Ingels, for whom the year also brought the opportunity to design the pavilion of the Serpentine Gallery. But without a doubt the event of Spain’s year was the bid for the new enlargement of the Prado Museum, in which the likes of Souto de Moura, Chipperfield, or Koolhaas took part, the commission ultimately going to Norman Foster, associated for the project with the Madrid architect Carlos Rubio.

In the world scene, surely the most important competition was for the Museum of the 20th Century at the Kulturforum of Berlin, won by Herzog & de Meuron with a colossal brick shed that, combining the elemental with the iconic, culminates the partners’ extraordinary annus mirabilis. Heading the awards chapter are the Imperiale of Mendes da Rocha (who also capped the Ibero-American Biennial prize) and the RIBA Gold Medal of Hadid, who in the year of her demise also landed one of the Aga Khan awards, whose promotion of pluralism culminated in this edition with the honors bestowed on projects like the Superkilen in Copenhagen or two projects of basic construction and social commitment in Bangladesh, a mosque that does without a minaret and a community center that blends into the landscape. Back on the homefront, the National Prize for Architecture went to Rafael Moneo and the one for Restoration to Antonio Almagro, and the CSCAE Gold Medal was split between Victor López Cotelo and Guillermo Vázquez Consuegra.

In the section on losses, Zaha Hadid was joined by the Mexican Teodoro González de León, the French Claude Parent, the British Peter Blundell Jones, or the young Portuguese Diogo Seixas Lopez, besides the Spaniards Joaquín Casariego, Vicente Patón, Luis Miquel, or Fernando Redón, of different generations but united in the endeavor to do something for the world through architecture, an optimistic profession that faces the gale of populism lashing our societies with no other weapon than the defense of rigor and excellence.