What has perhaps been the worst year in half a century, 2020, comes to a close with a hope-inspiring image: the picture of elderly people and nurses receiving the first doses of the vaccine. Hope-inspiring because it a sign that the thick fog in which world health, economics, and politics are immersed is finally starting to dissipate, and that the end of the coronavirus is in sight.

It is not however clear whether the launching of the mass vaccination campaign signals the beginning of the end of the pandemic or – as Churchill enunciated in another tragic context – simply “the end of the beginning.” Neither is it clear, as a matter of fact, that vaccination is a genuine panacea. Not only because it is very likely that face masks and lockdowns are here to stay for months or even years, but also because – as some experts predict – the hope-bearing picture of inoculations may in truth be a disturbing ushering-in of a period marked by new waves of infection that could well prove even more lethal than Covid-19.

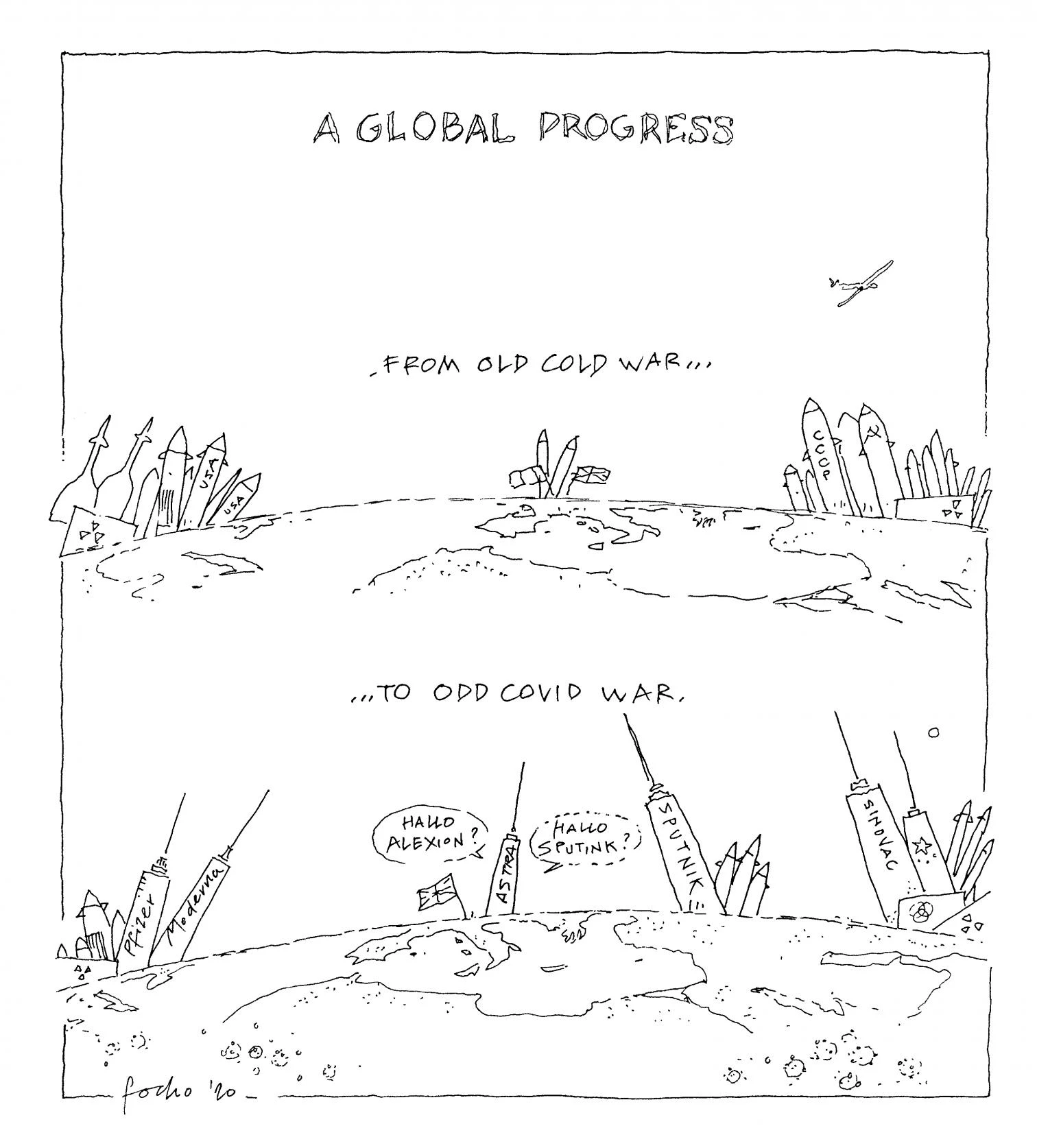

However it may be, 2020, the year of the plague, has brought with it a widespread sense of persistent uncertainty, lingering malaise, and latent fear that humanity had not known since Cold War times. If in one case the cause was the atomic bomb, in the other it has been the coronavirus. Almost always, what’s most scary is not the visible danger, but the invisible enemy that lurks in the air we cannot stop breathing.