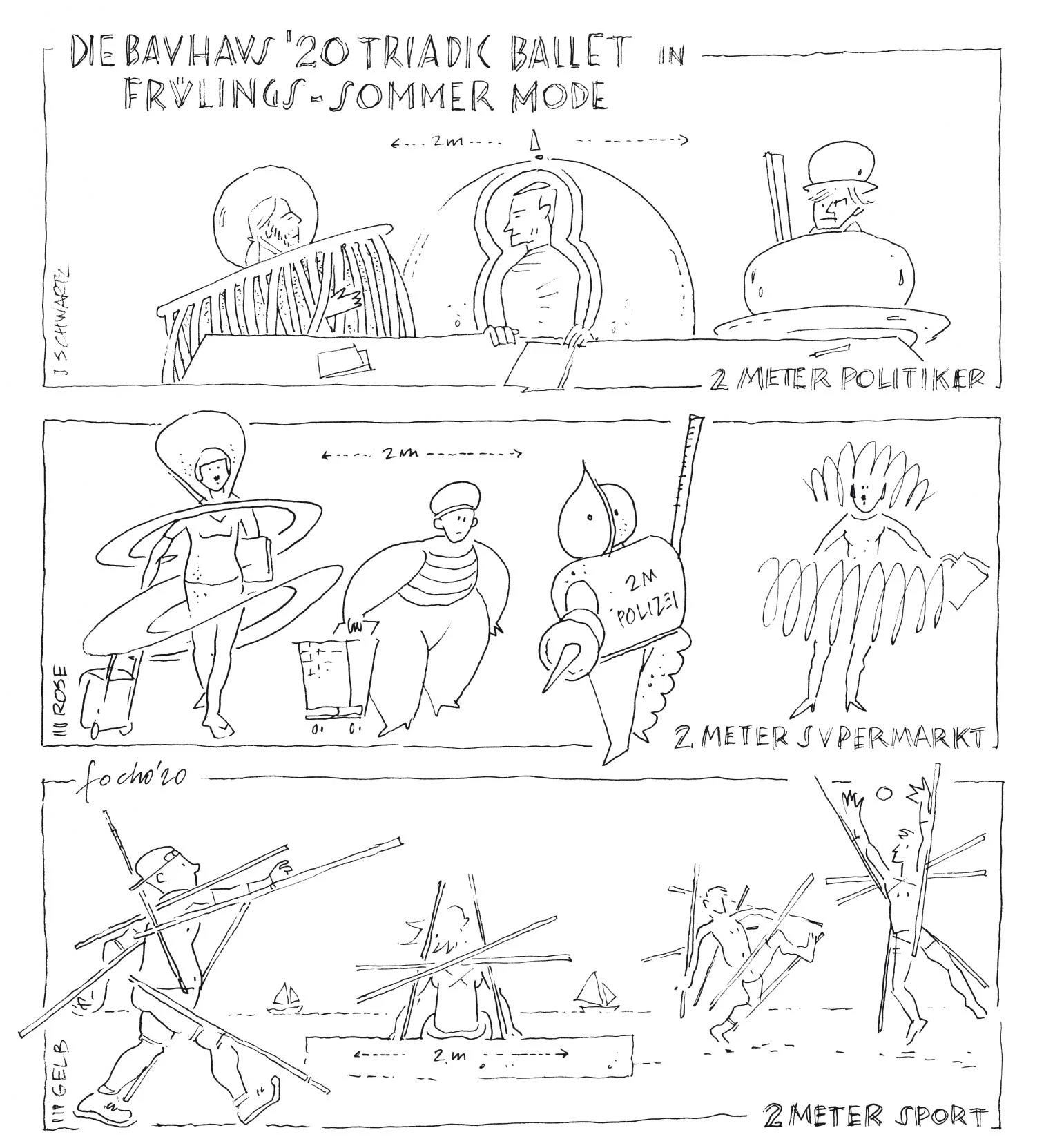

One way To distinguish liberal democracies from totalitarian regimes is by comparing the aesthetics of their respective popular demonstrations: on the one hand, organic masses whose chaos is an expression of spontaneity or freedom; on the other, crowds arranged in a unanimous disciplined structure that spells absolute state control. In this matter, too, the ongoing covid-19 pandemic has disrupted all predictable scenarios and commonplaces. The unavoidable ruling to observe physical distancing from one another and the temporary curtailing of basic civil rights are throwing light on the disturbing fact that a queue for viral testing in Kuwait, lunch break in an enormous Chinese factory, and the First of May celebrations in Lisbon take the same form, rigorously choreographed, of bygone parades on Red Square in Moscow or the huge ceremonies held in Pyongyang in honor of Kim Jong-il.

Such spectacles of spontaneous geometry of masses are in all likelihood the most intuitive way for us to understand the extent to which the pandemic is calling into question the very system we live in and take for granted; a system which in great measure is grounded upon the freedom of movement of people, goods, and ideas. Order and discipline are proving to be one of the most efficient responses to the coronavirus crisis, but, as in stories by Kafka and Chesterton, underneath the impeccable, highly attractive aesthetic of that order perhaps lies the code of the most terrible nightmare.