Fortunato Depero was one of the leaders of Italian futurism, but is considered a ‘minor master.’ Crouching in the shadow of Marinetti Balla or Boccioni, scoffed at for his link to fascism, Depero’s fate has been that of the part of the Italian avant-garde which the historiography, for lack of a better word, calls ‘second futurism’: a successor, not to say diminished image, of the first futurism, the good and heroic one. Though this is partly true, what happens with Depero is the same with other ‘minor’ masters; as Panofsky pointed out, they express the tone of their epoch better than the big names do, and end up being more interesting.

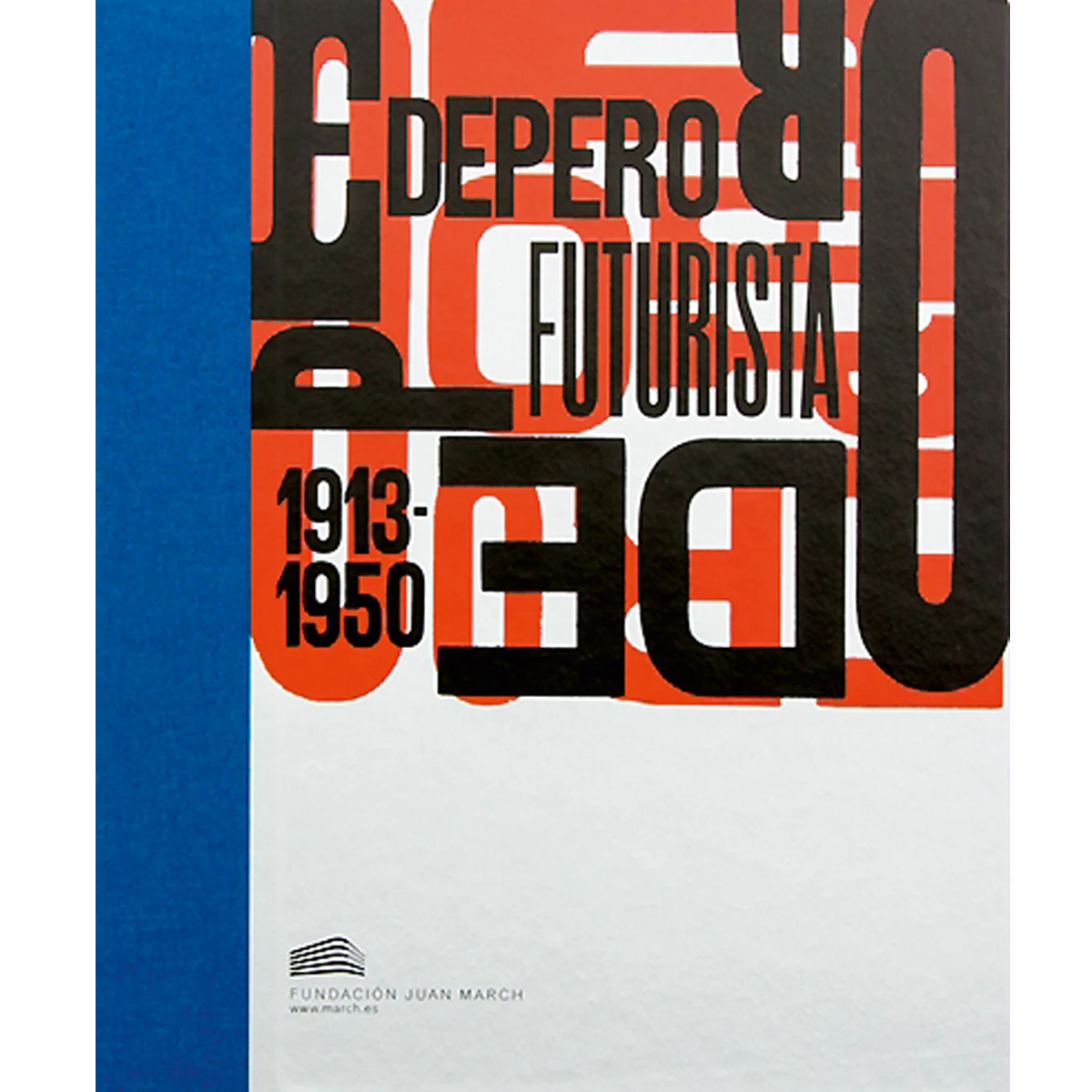

A century after Sant’Elia published his ‘Manifesto of Futurist Architecture’ shortly before being killed in the war he glorified, the Juan March Foundation presents the first major retrospective on Depero, and with it a catalog which is already the best monograph on the artist. This attests to the interest he has sparked in the wake of exhibitions in London (2000), Budapest (2010), and Barcelona (2013), and the publication of two books intended to make up for the historiographic ill luck of someone named, paradoxically, Fortunato.

Born in Rovereto, in Italy’s Trentino region, Depero (1892-1960) was perhaps the member of the Italian avant-garde most stubbornly faithful to futurism. His fidelity was forged at Boccioni’s 1915 exhibition in Rome. It was there that he made his vows to futurism: glorify dynamism, the machine, and war; multiply viewpoints; free words from grammar; and fuse art with life for the sake of that fugitive aesthetic dreamt by Baudelaire.

In Depero, loyalty to futurism did not lead to dogmatism – Marinetti almost ‘excommunicated’ him –, nor to creative sclerosis, but aligned itself with the pragmatism of ‘minor’ masters. Far from keeping to painting and sculpture, Depero tackled all disciplines touching on ‘everyday life’.

So, confined in Rovereto – except for a long stay in New York, with his beloved skyscrapers and roaring automobiles –, Depero experimented with all genres: he was a playwright and a designer of mechanical sets and costumes that could produce lights and sounds for stagings that were both abstract and naïf; a maker of toys ahead of their time, of intarsia rugs with color schemes sewn stitch by stitch; a creator of an early ‘artist book’, the ‘bolted book’ that could not be shelved, and of a ‘portable museum’ like Duchamp’s; an author of minimalist fair pavilions and ‘typographic architectures’ preempting Venturi by half a century; and a graphic designer who turned Campari Bitters ads not so much into sophisticated objects but into self-publicity posters, setting a course later followed by art, increasingly contaminated by the ‘commodity fetishism’ that Marx described as the spirit of the times. Certainly not minor achievements of a ‘minor’ master.