From Austerity to Solidarity

One exhibition and two congresses have promoted a more efficient use of resources and an emphasis on our common spaces as a tool to face today’s crisis.

PLACING ITSELF at the service of architects but also at the service of those who live in buildings and cities, AV/Arquitectura Viva has called for austerity and solidarity as a way of dealing with the crisis that afflicts so many European countries. The product of a collective reflection that in the past two years has given rise to a series of events, exhibitions and publications, this minimal and essential program stretches the reach of our editorial work towards larger fields. A prominent example of this can be found in our collaboration with the Fundación Arquitec-tura y Sociedad in organizing international congresses in 2010 and 2012.

The first of them, titled ‘More for Less’, set out to deal with the current crisis in a spirit of optimism. It was a reminder of the need to always see the bottle half full, and an invi-tation to take the necessary austerity as an opportunity to correct the wasteful habits of the past decades. Not only economic crisis, but also climate change and the progressive exhaustion of fossil fuels, prod us to try to offer more efficiency, more comfort and more beauty with less consumption of non-renew-able resources: to build with lower budgets, saving on materials and energy, is without a doubt an imposition of the circumstances, but also a technical and intellectual challenge, a hygienic slimming cure yielding healthy ethi-cal and aesthetic fruits. Four months after this congress the Museum of Modern Art opened an exhibition – ‘Small scale, big change’ – that presented in New York the work of several of the architects who had participated in the Pamplona event, and it was encouraging to verify that the same paths were being explored on both sides of the Atlantic.

The two congresses in Pamplona gathered figures from the five continents: half a dozen Pritzker laureates along with emerging architects, historians, art critics, sociologists, writers and philosophers like Zizek.

Nevertheless, the call for austerity is insufficient if not accompanied by a call for solidarity, in such a way that the sacrifices made necessary by the crisis are distributed fairly and the problem of solving it is entrusted to a shared effort; a message that the Foundation’s second congress summed up concisely in the slogan ‘The Common’. We need to put emphasis on what brings us together, from public spaces and buildings to those features of everyday life that establish community links among us. It is not enough to censure excess; we must promote all that which is shared, because only from that which joins us together can we extract the strength necessary to succeed in resisting the economic and social storms that are putting our institutional fabric at risk. Another international event, the Venice Architecture Biennale, opened later in the year with a similar title, ‘Common Ground’ – with many speakers in the congress taking part in the main exhibition, including myself –, and once again it was stimulating to know that our preoccupations were being addressed in larger events.

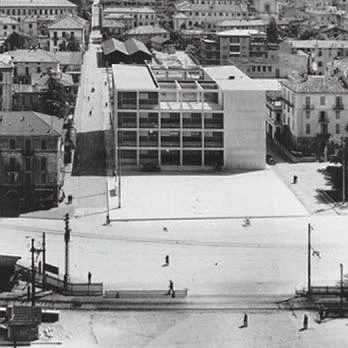

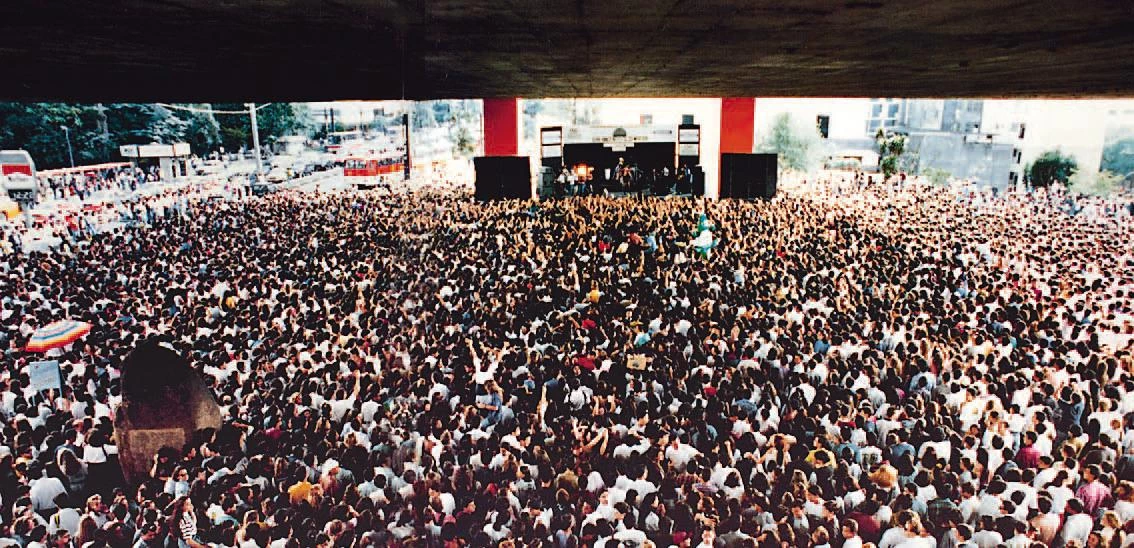

The multitude transforms buildings and cities with its choral presence, be it in front of Terragni’s Casa del Fascio, inside João Vilanova Artigas’s School of Architecture or under Lina Bo Bardi’s Museum of Art.

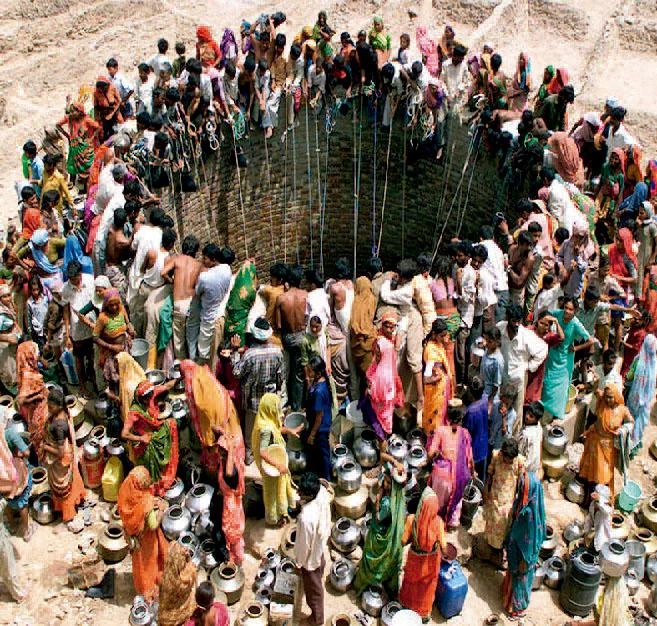

The Venice Biennale used the image of a crowd to express its intentions graphically, and crowds were also the guiding thread of my own presentation at the Pamplona congress. Urban spaces and large public buildings alike take on significance when they become arenas for civic life, and it is the choreography of the celebration or the protest, the spectacle or the mourning, that gives life and meaning to the inert matter of architecture. Whether a political rally in front of Giuseppe Terragni’s Casa del Fascio, a student gathering in João Vilanova Artigas’s School of Architecture or a concert under Lina Bo Bardi’s Museum of Art, the unanimous multitude transforms the dry geometry of construction into the warm pulse of ideological or aesthetic communion: from Alpine Como to tropical São Paulo, people ap-propriate public space, be it an urban square, the inside of a doorless building or the plaza under a cultural center.

Museum of Art in São Paulo by Lina Bo Bardi

Museum of Art in São Paulo by Lina Bo Bardi

In protest or celebration, popular gatherings blur the architectural frame, as in Cairo, Madrid or New York, or else turns monuments into backdrops or reference points, as in the images of Thailand or Athens.

Tahrir Square, Cairo

Protest in Greece

Prayer in front of a mosque in Pattani, Tha

Of course a fascist demonstration in sup-port of the armed annexation of an African country by a European nation is not the same thing as a mass university protest or a noisy concert with swarms of young people, but all these experiences of collective life are similar in their exaltation of the pleasure of being together and the fascination of contemplating how the massive coinciding of persons dilutes the scenes of encounter, whether urban or architectural. At the same time, the choral unanimity of the crowd annuls the individu-al conscience and is a breeding ground for demagogy, populism or the gales of emotions of the kind that pull nations towards some manifest destiny or foretold catastrophe. The indignant choreography of Cairo’s Tahrir Square was later echoed in Madrid’s Puerta del Sol or in New York’s Zuccotti Park (base of the ‘Occupy Wall Street’ movement, which cropped up in other spots of the city), and in all cases – as much in the Arab Spring as in the Spanish 15-M rebellion or the anti-capi-talist demonstrations in the United States –, spontaneous sympathy for their commendable motives has often been mixed with suspicion with regard to the uncertain outcome of their collective drive.

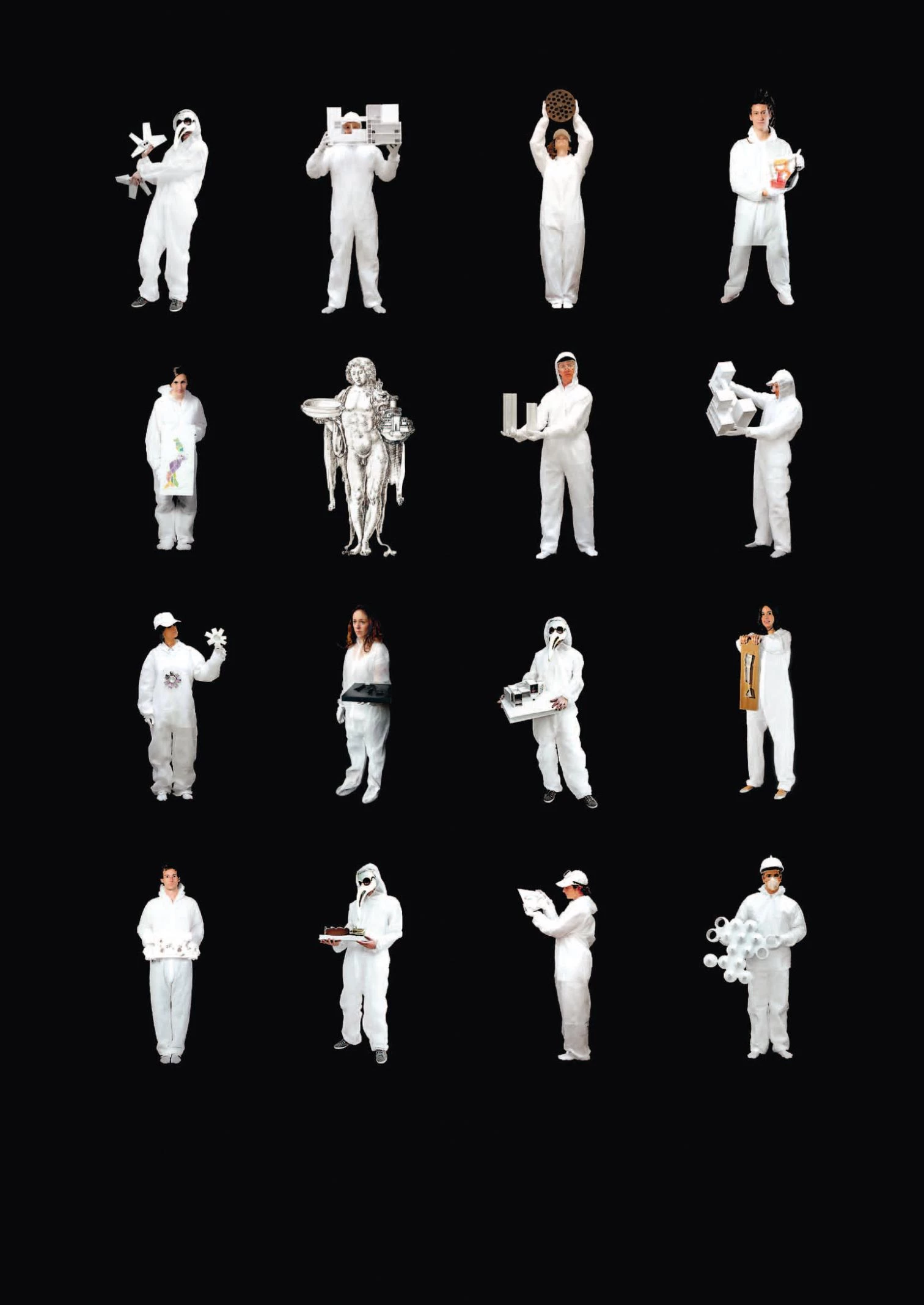

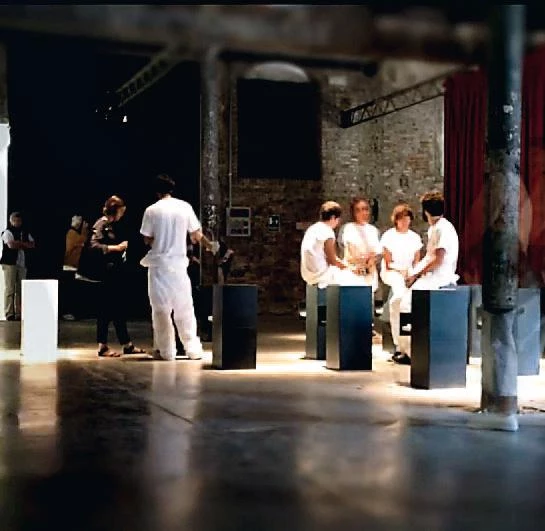

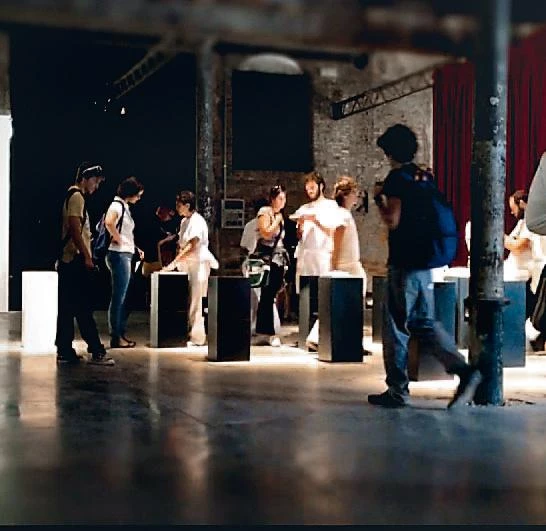

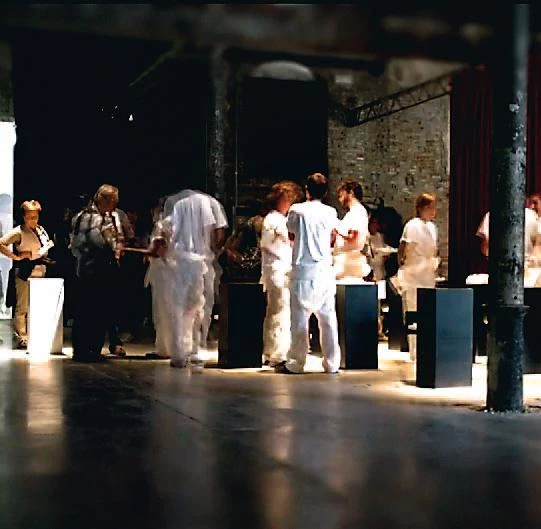

The ‘common ground’ of the Venice Biennale was interpreted in ‘Spain mon amour’ with architecture students holding and explaining models of recent buildings, joining the classical tradition with a critical intention.

There is a space without cracks where in-tentions dissolve and the multitude asserts, above everything else, its own condition. A carnival or a protest can transcend their fes-tive or political nature to become colorful stage scenes where clothes, flags or banners express the unanimity of sentiment. When such a thing happens, architecture recedes into the distance and only appears as a refer-ential landmark or theatrical backdrop, be it a bulbous mosque in Thailand or a neoclassi-cal building in Greece. In the same way, the well-worn, inhabited building turns into an-other, very different one – difficult to notice in so many exquisite photographs showing contemporary architecture as silent empty works – and constructions become common only when their spaces vibrate with the mur-mur and swarm of the people who use or visit them, becoming places where the uniqueness of the forms dissolves in the choreography of civic life, and where the intellectual or artis-tic language of their authors fades before the spectacle of popular vitality.

Perhaps in tune with this sentiment, in the exhibition ‘Spain mon amour’ at the Venice Biennale, fifteen students dressed in white held models of fifteen recent Spanish works, simultaneously presenting the achievements of our architecture and reflecting the pro-fession’s current situation through a visual mixing of the classic iconography of saints or kings bearing models of churches or cities, and those installations that use mass labor with a critical purpose – though tempered, in this case, by the light perfume of the commedia dell’arte. In shifts lasting a week the architecture students conversed with visitors, explaining the works they carried while com-menting on the Spanish situation or express-ing their own hopes and fears, thus becom-ing both interpreters and protagonists of the exhibition. Dubbed ‘unemployed angels’ in some media coverage, they offered an image of the country that, without hiding realities, was almost the opposite of that conveyed in the dramatic photographs published in the in-ternational press. Indeed ‘Spain mon amour’ was, as we presented it then, “a celebration of a period, its architects and its buildings, but also an elegy for a time that has come to an end, a gentle manifesto against a dislocated present and an invitation to think the future in a different way”.

The dramatic morbidity of the crisis, which has already overstepped the bounds of the strictly economic or financial terrain to encroach on the immaterial sphere of values, invites us to reset the architectural discipline – setting hopefully aside all traces of narcis-sism or self-complacency and leaving behind the excesses of recent times – and restore its mission as a profession of service, closely im-bricated with the satisfaction of social needs, which have a technical and functional, but also a strictly aesthetic and symbolic dimension. Architecture will thus have to make efforts to give ‘more for less’: more security, effi-ciency and beauty while using fewer resources and behaving more responsibly towards the planet; but it will also have to pay attention to ‘the common’: to everything that we share and that therefore binds us together more tightly and with greater solidarity. This more austere architecture will find its elegance in its reduc-tion to bare essentials, and this more socially oriented architecture will find its minimal aes-thetic in the maximal ethic of life in common.