Competition by Ballot

The architects of Pamplona’s San Fermín Museum and Santander’s regional government headquarters have been selected through direct public consultation.

Architects are mistrustful of ballots. Most of the masterworks they admire are products of despotism or theocracy, and they tend to think that the esthetic judgments of common people are predictable and abominable. Trapped between the romantic narcissism of avant-gardes and the elitist disdain for the mediocrity of popular tastes, they react to the sovereignty of the hoi polloi with offended spririts and impatience: to subject their projects to the verdict of ballots, to expose their work to the uninformed appraisal of profanes in the material, is a deliberate humiliation. But architecture is a useful art and a public art, and as such, it cannot avoid appearing in the court of general opinion, an obligation rendered all the more peremptory when involving public buildings meant for the service of all and funded with the money of all. There are in-deed elements and circumstances accessible only to the trained eye; but the function of the expert is, precisely, to make the obscure intelligible and help laypersons form their own judgment.

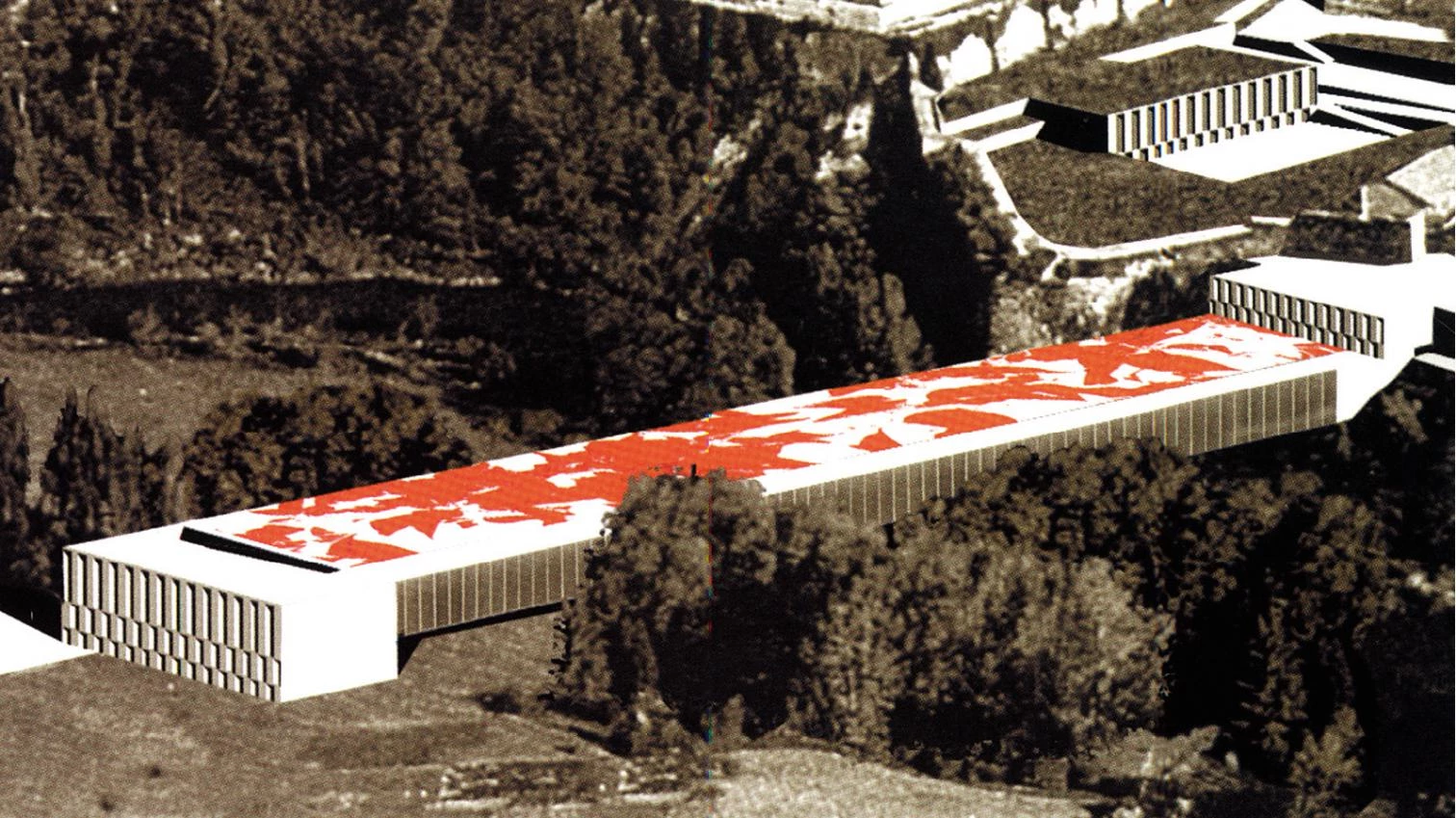

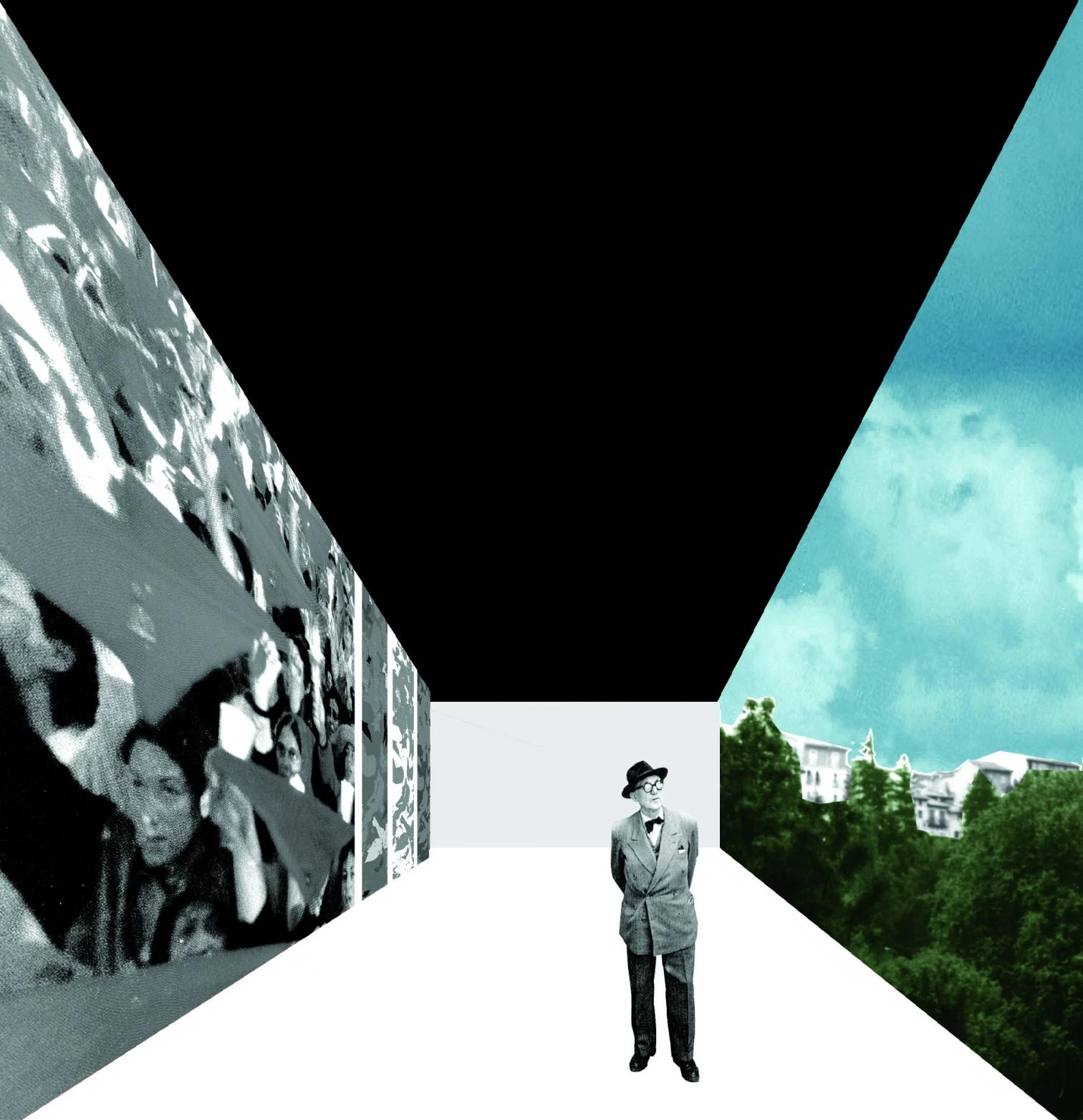

Both public opinion and the decision of the jury favored the proposalof Mansilla & Tuñón in the competition of the San Fermín Museum.

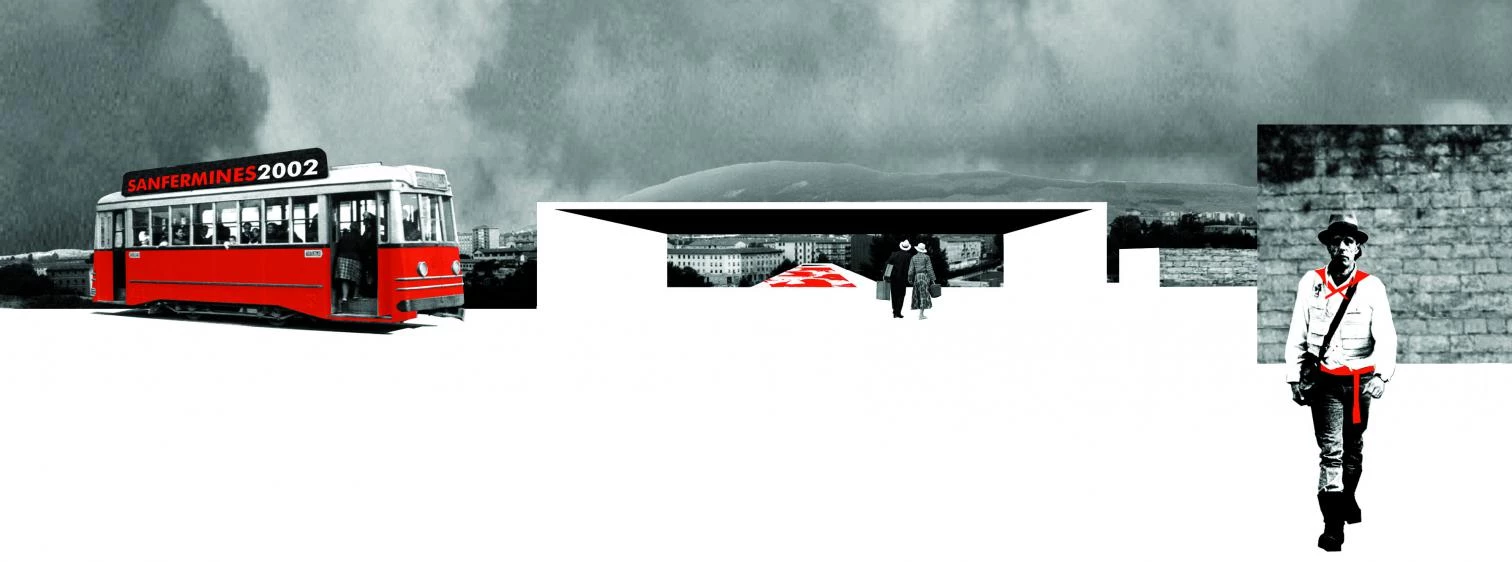

In Pamplona, Town Hall tasked eight architec-tural teams to draw up a proposal for the future Mu-seum of the San Fermín Festival, an important work given the symbolic significance of the city’s famous Fiesta and Encierro, but of rather imprecise uses and with an equally vague location, halfway between the fortified historic quarter and a suburban extension. The Japanese Arata Isozaki, the Dutch Erick van Egeraat, the Portuguese Rocha and Byrne/Mateus, Madrid’s Perea and Moreno Mansilla/Tuñón, the Catalan Jordi Garcés, and the team formed by Navarra’s own Mangado and the Boston-based Machado/Silvetti competed for this emblem-atic project, submitting eight painstakingly prepared proposals that were also markedly heterogeneous, no doubt as a consequence of the deliberate indefinition of the competition brief. With the aim of stretching the scope of the debate, the jury selected three of the entries – situated, respectively, at a bastion of the old city, on the edge of the anonymous residential zone across the river, and as a bridge between both areas – and convoked the architects for a second phase to be held after an ex-hibition and a public vote.

Overall, the ballots left in the two places the mod-els were displayed in and the survey conducted among readers of the Diario de Navarra pointed in favor of the museum-bridge conceived by Luis Moreno Mansilla and Emilio Tuñón, with 797 votes, followed closely by the bastion building of the Porto architect João Álvaro Rocha, with 607, and at a greater distance by the laconic boxes of the Lisboans Gonçalo Byrne and Manuel Mateus, with 206. After hearing out the contestants and examin-ing the modified versions of the projects, the jury pronounced itself in the same direction as the pop-ular vote, commissioning the San Fermín museum to the Madrid architects – a risky decision given the visual impact of their lyrical proposal for the park on the bank of the Arga River, but very safe when one considers the talent and realism demonstrated by the brilliant tandem of architects in their Zamora and Castellón museums. So in Pamplona they will be building at the feet of their old master and mentor Rafael Moneo, who is already erecting the screens of concrete of the Archives of Navarre over the fortified perimeter that looks over the river and the future museum – a Moneo, by the way, who himself has won a popular vote in the even more recent competition for the new seat of the Cantabrian Government in Santander.

Rafael Moneo

Peter Eisenman

Polemic for the imbalance between plot and program, the competition for the seat of the Cantabrian Government in Santander was entered by five teams; after a public voting on the projects, the commission went to Rafael Moneo.

Carlos Ferrater

David Chipperfield

Jéronimo Junquera

In this case, the regional administration invited seven architects to draw up a colossal construction for an uncomfortable lot. The Swiss Mario Botta and the Santander-born Juan Navarro Baldeweg declined for reasons unspecified but probably having to do with the disproportionate demands of the brief, which forced the insertion in the place of a volume excessive in all respects, upsetting the regular density of the consolidated city. The other five professionals confronted the challenge of the imposed scale through different strategies. The Amer-ican Peter Eisenman managed to soften the building’s impact on its surroundings by fracturing the volume into curving pieces that stretched into an adjacent property. The Catalan Carlos Ferrater broke down the project into oblique fragments clad with an aleatory facade. The Madrid architect Jerónimo Junquera put part of the program inside a large 15-story tower, thereby better adjusting the remaining volume to the urban context. The British David Chipperfield in turn stayed clear of domes-ticating size and proposed a defiant, gigantic, elemental cube of glass. And the Navarrese Madrid-based Rafael Moneo tried to compensate for his titanic prism of glass through a huge stepped void inside the building’s volume that would serve as a public entrance.

Here, too, the opinion of the citizens was solicited, through an exhibition of the models that traversed the region and an exhibition of photomontages on the web. Summing up the votes in the ballot boxes and those cast via Internet, the winner was Moneo, with 1,759, followed by Eisenman with 1,528, Junquera with 1,415, Ferrater with 1,172, and, way behind, Chipperfield with 348. Unlike in Pamplona, where the poll only endeavored to gauge public opinion, in Santander the results were bind-ing, the administration having announced from the start that the final project would be chosen from among the three most voted. With Eisenman dis-qualified for venturing beyond the specified site (at the same time, paradoxically, that the regional government announced the future purchase of adjacent land so as to relieve the building a bit, perhaps to cushion complains about the sheer scale of the operation), the race boiled down to Moneo, Junquera and Ferrater, and the Cantabrian president opted for the one most voted, Rafael Moneo.

Rafael Moneo

Peter Eisenman

Jerónimo Junquera

Carlos Ferrater

David Chipperfield

There are many possible reasons for being wary of architecture determined by plebiscite. A democ-racy of consensus may find itself under strong pressure to build consumerist architectures, and it seems logical to defend institutional works from the amiable triviality that consumers demand in commercial construction. But with the unanimous spread of junk TV and junkspace, it is doubtful that the only way out is the defense of a ‘cultural exception’ administered by experts. The last Turner Prize fell upon Martin Creed, a British artist who exhibits an empty room lit up at intervals of five seconds, and in reaction to the subsequent polemic some critics appealed for laypersons to abstain from commenting on artistic issues, a task to be left to specialists. I do not know if such arrogant rejection of populism is the most adequate road for contemporary art to take, but I am sure it is not the best for a public art like architecture. To scorn sales figures, box office incomes and audience shares does not imply doing away with the public altogether, and architects’allergy to ballots should not exclude citizens from decision-making, or architecture from accountability.