Austral Chart

Noviembre

Chile is having days of wine and roses. Neither the regular Mapuche protests nor the cases of corruption that have tainted the Concertación government, nor the judicial vicissitudes of a dictator lost in his own labyrinth of solitude have managed to alter the overwhelming self-esteem reflected in the Bicentennial Poll, conducted in preparation for the 2010 celebration and recently disseminated by El Mercurio. Three out of every four Chileans consider their homeland “the best country in Latin America to live in,” according to the poll published by the Santiago daily. Spain too, incidentally, stands out in the survey results as the most admired, ahead of the United States, a perception that accompanies the substantial Spanish presence in key sectors of Chile’s economy: Endesa controls 50% of electricity generation, Movistar supplies 47% of mobile phones, Santander and BBVA jointly cover 30% of banking, Agbar has 35% of its sector’s clients through Aguas Andinas, and firms like Sacyr, Cintra, OHL and ACS are leaders as builders of infrastructures ranging from airports to motorways; figures which elsewhere in Latin America would arouse more resentment than appreciation.

In this case, the admiration is to a large extent mutual, and the diagnosis published in El País in April by Alain Touraine, “Chile as a Model,” is shared by most of the political and corporate leaders in Spain, where both Michelle Bachelet and her mentor Ricardo Lagos are praised for their determination to make economic growth and social justice compatible, as well as for their lucid ability to combine remembrance of the victims of the dictatorship with the quest for consensus and national reconciliation. This latter objective is symbolically materialized in the Palacio de la Moneda, the grand classicist Baroque building whose construction by Joaquín Toesca in the 17th century is portrayed in Jorge Edwards’ novel El sueño de la historia, and the bombing of which on 11 September 1973 be-came the tragic emblem of General Augusto Pinochet’s coup d’etat against Salvador Allende’s government. It is the presidential residence that Lagos decided to clear of demons through a large cultural center buried at its feet, underneath the ceremonial palace square: a colossal volume lit naturally from above and flanked by ramps, designed by architect Cristián Undurraga, which represented the country in the last Biennale di Venezia and which itself was the venue for the exhibition and conferences of Chile’s own Bienal de Arquitectura..

President Lagos decided to transform the image of the Palacio de la Moneda, famously bombed during Pinochet’s military coup, with a vast, toplit cultural center excavated under the ceremonial square that stretches before it.

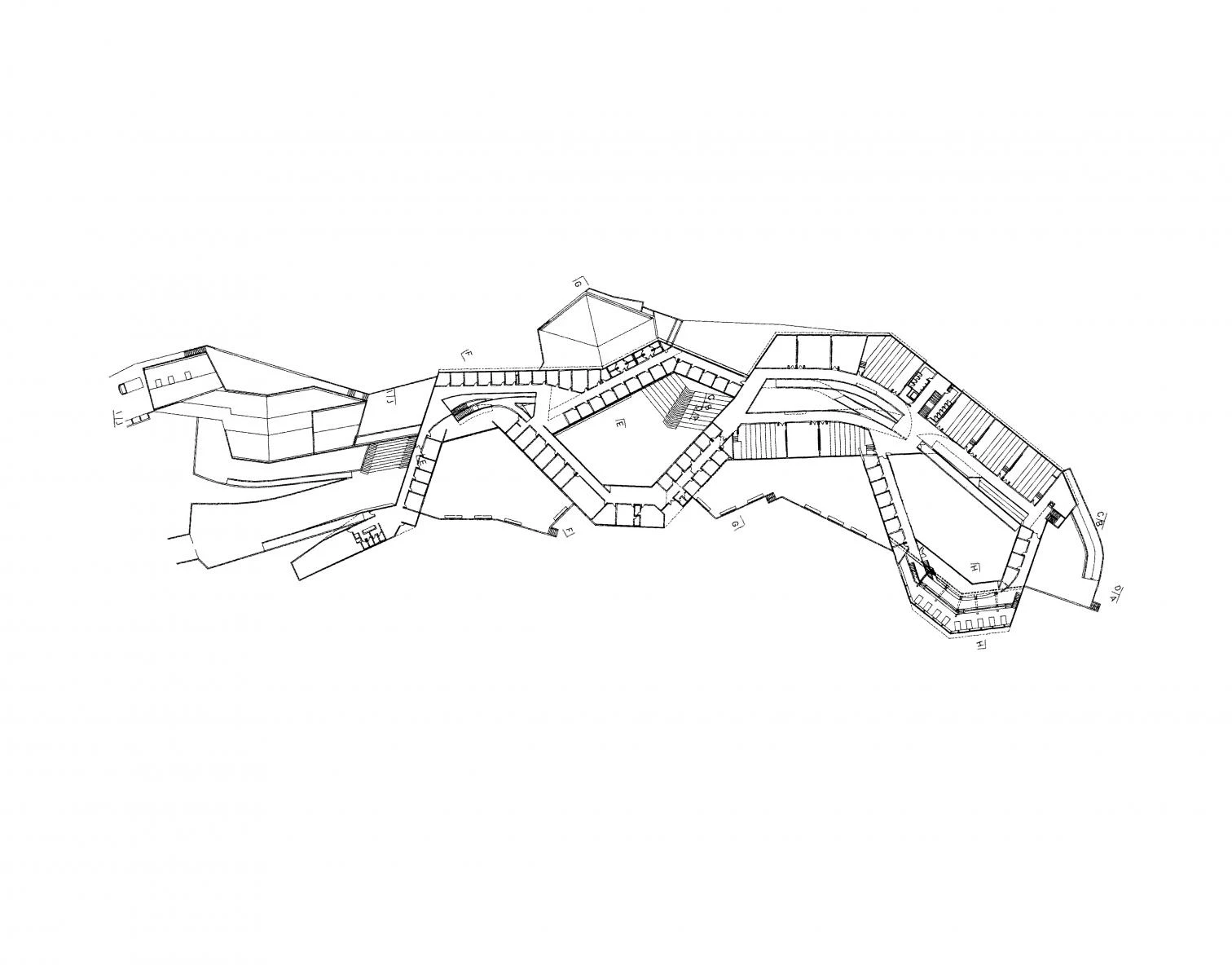

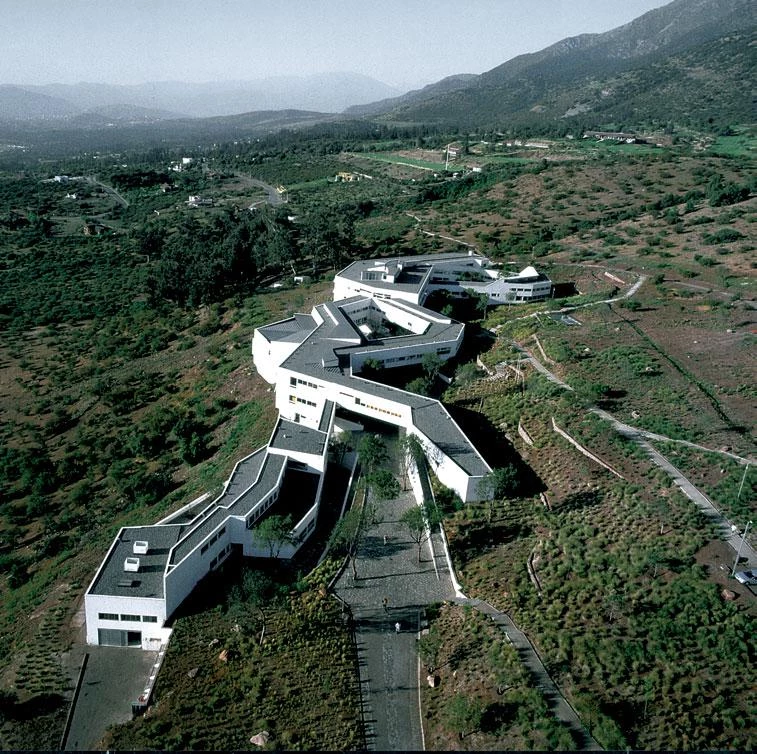

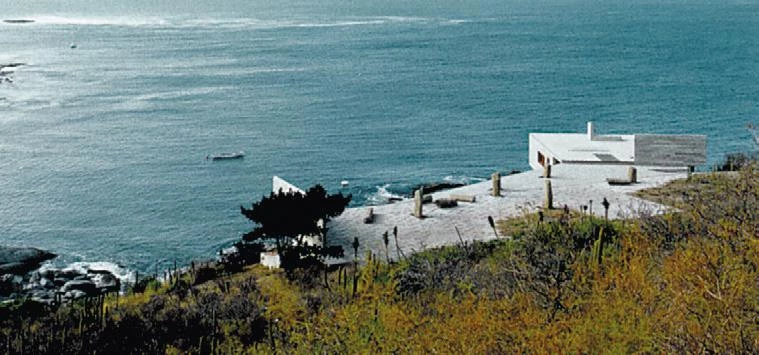

The selection of projects for the exhibition makes a plausible portrait of the here and now of Chilean society, whose economic boom is thanks to private initiative taking the lead, leaving little room for state participation, so unlike the way things work in many European countries, where architecture that stands out in any way is mostly commissioned by public clients. Projects of this nature are rare in Chile. Works as formidable as the Elemental social housing development in Iquique, spearheaded by Alejandro Aravena, or as polished as the public services building in Concepción, designed by Smiljan Radic, are exceptions to the rule. The bulk of the exhibition shows houses built for affluent clients – among these the extraordinary Casa Poli, a neo-plastic prism designed by the young team of Mauricio Pezo and Sofía von Ellrichshausen on a vertiginous cliff over the Pacific – besides private universities like Mathias Klotz’s Diego Portales or José Cruz’s Adolfo Ibáñez, corporate headquarters, the inevitable winery, and the no less inevitable exotic hotel, in this case Germán del Sol’s very appropriately named Remota.

The Chilean landscape shapes both the Adolfo Ibáñez University by José Cruz (right and center) and the Hotel Remota by Germán del Sol (below), two works by the authors of their country’s pavilion at the Seville 1992 Expo.

With a rich Spanish representation, culminating with Rafael Moneo’s stellar appearance on closing day, the series of lectures and debates organized by the Bienal revealed both how proud Chileans are of their own achievements and how cosmopolitan they are in their curiosity about what goes up abroad, making for a professional panorama whose intellectual and aesthetic proximity to Europe or the United States contrasts with its geographic distance from both. Neruda’s mythical Chile continues to exist in the country’s vast territory and in the moving devotion of those who pilgrim to his house in Isla Negra – where he is buried in the garden, facing the ocean and close to his devotional figureheads – like one visiting a national and poetic sanctuary. But the topographic and dilapidated beauty of Valparaíso is now undergoing refurbishment with the money of Chile’s new prosperity, the profits from its mines are being complemented by the vegetal splendor of ex-portable crops, and the warm valleys at the foot of the mountain range are filled with vineyards of impeccable geometry. There, the rows of vines are finished off with rosebushes to facilitate early detection of plagues, and perhaps this unexpected meeting of wine and roses is a good metaphor for the aromatic and euphoric moment that the austral country is enjoying. Collige, Chile, rosas.

Most of the best works have private clients, be it institutions, companies or families like those who commissioned Casa Pite by Smiljan Radic (right) or Casa Poli by Pezo & Ellrichshausen (below), both over the Pacific.