Carnival in Lent

In a world suffering the pain of austerity, the great celebration of the Shanghai Expo – two years after the Beijing Games –, is another expression of China’s rise.

The Shanghai Expo proposes extending Car-suffering from the effects of the financial crisis, and the whole of it faces the impact of climate change and the mutations of the economic, energy and territorial model that circumstances impose, China once again amazes the planet with the largest Fair ever, an XL event that shows the robust muscle of the Middle Kingdom. Two years after the Beijing Games, this economic Olympiad backs the financial and logistic centrality of Shanghai with an invest-ment in infrastructures – a new airport terminal, a highway network, 250 kilometers of subway and a remodelled riverfront – which exceeds 30,000 million euros, aside from 3,000 million (more than twice that of the Games) in the Expo itself, which takes up a surface twenty times larger than that of Zaragoza and hopes to receive between 10 and 15 times more visitors than the Fair held there in 2008.

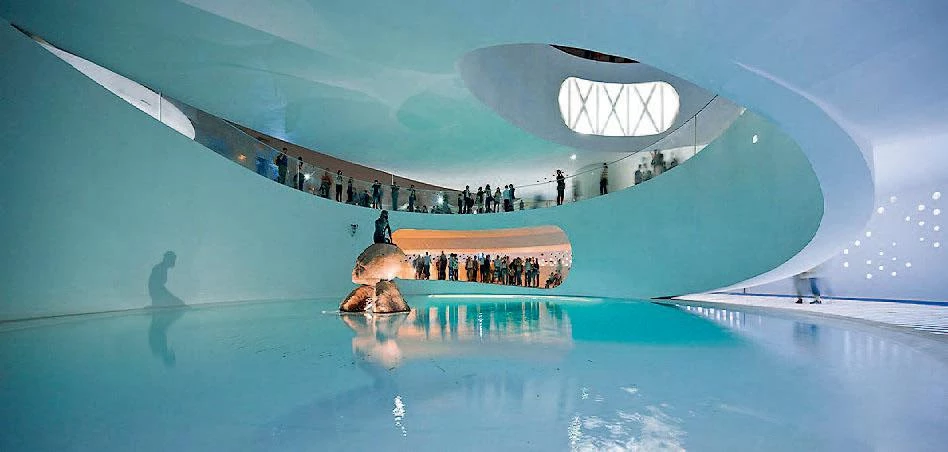

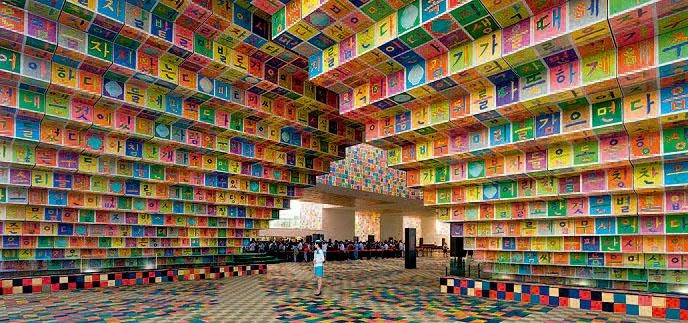

This colossal Expo, which breaks the record of participation with 189 countries, gathers scores of temporary pavilions – from the wavy, calligraphic wicker scales that represent Spain to the cyclist loop of Denmark, the golden dunes of the Emirates, the pixelled typography of Korea or the suggestive and lyrical British cathedral of seeds – all in the shadow of the huge permanent construction of the host country: a bright red inverted pyramid that stacks prismatic pieces to recall traditional wood construction with its megastructure. Tradition is, however, somewhere far in this city bristling with skyscrapers, which grows at an unstoppable pace, and whose violent dynamism blurs the traces of the past just as it has moved 55,000 people to free up the plot for the Expo on the banks of the Huangpu River, showing that the friendly motto of the event (‘better city, better life’), is not incompatible with the ruthless expediency of its government.

The skyline of Shanghai with the Pudong towers and the fireworks that opened the Expo offer complementary images of China’s prosperity, a society and a State that vindicate their rightful place in the world.

The dizzying transformation of the city has at least three noteworthy features: the visibility of planning, expressed in the huge model that can be seen in the Urban Planning Exhibition Hall, where both the existing buildings and the planned ones spark the curiosity or scrutiny of citizens and visitors; the search for efficiency through public transportation and urban density, which is achieved replacing many of the 19th century lilongs – row houses around a private alley, similar to the British mews, and by the way examples of sustainability for urbanists like Denise Scott Brown – with crammed residential towers of thirty floors; and decentralization through the creation of satellite cities equipped with all services, including some exemplary ones like Dongtan, an eco-city in Chongming designed by the British firm Arup, within the general plan produced by the Chicago office of SOM for this island on the Yangtze River Delta, which foresees a population of 2 million with urban cores compatible with organic agriculture and green industries, and that hopes to become an example of environmental respect and energy efficiency.

Shanghai is to such a great extent associated with the spectactular profile drawn by corporate skyscrapers – the Jin Mao completed as a pagoda or the World Financial Center as a bottle opener, and also the Shanghai Tower, which will be Asia’s tallest building when completed in 2014 –, with the proliferation of cranes – at some point it was said that half of the cranes in the world were there –, or with the harsh determination in population moves to make room for new projects, that it seems ex-travagant to ponder further upon what Peter Rowe, former dean of Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, calls “the greening of Shanghai”, a process that includes the new metropolitan parks, the re-generation of the river banks and an emphasis on sustainability for which projects such as the one in Chongming serve as reference.

The Chinese pavilion in the Expo rose over the rest of them with its titanic tribute to traditional construction techniques; the Spanish one, wrapped with wicker, had a giant baby-doll as symbol and tourist attraction.

However, the old China of coal power stations and dirty development is being replaced at a huge speed by a China that aims to lead the great market of this century, that of clean technologies, and not so much because of deep ecological convictions but due to the employment and prosperity that this growing field generates: the data recently presented by Bruce Usher in the Herald Tribune are thought-provoking, and should also urge to take action. In 1999, the country manufactured 1% of the solar panels, and in 2008 it was the first world manufacturer, with 32% of the market; and according to a World Bank report, in 2004 China promoted 5% of the clean development projects in the world, a figure that in 2008 had reached a barely imaginable 84%. In 2009, its investment in renewable energies almost doubled that of the United States, its main technological, financial and geopolitical rival, and at the same time its interlocutor and partner in the G-2 which governs the planet.

For many, the Expo of Shanghai is a large showcase for the Chinese model, that unique combina-tion of single party and free market that today – as the survey of the American Pew Research Center featured in The Economist shows – exerts an increasing influence in the developing countries.The popularity of what can be called ‘autocratic capitalism’ or ‘market communism’ proves – using the term coined by Joseph Nye – the ‘soft power’ of China, but worries its leaders, fearful that such visibility may provoke the United States, keen to maintain ideological leadership. However, what the American consultant Joshua Cooper Ramo bap-tized in 2004 as the ‘Beijing consensus’ is increasingly challenging the ‘Washington consensus’, and the Expo has coincided with the release of several books by Chinese and American analyists that describe with enthusiasm or reluctance the transition from the China that absorbs foreign experiences to the one that exports its own model: from the China that learns to the one that teaches.

Two of the most striking pavilions of the Expo were those of Korea and Denmark (above), and the most intriguing happened to be the British one, a ‘cathedral of seeds’ built with translucent poles resembling needles (below).

But this planetary event, whose size challenges the increasing irrelevance of universal expositions – superseded in their commercial dimension by the global market, and in their recreational aspect by the industry of spectacle –, is today above all a vehicle of patriotic pride, and with it China asserts its new place in the world: the choral presence of nations is an acknowledgment of China’s rise, and also an expression of a desire to promote their own ‘country-brand’ in that huge market. Within China, the Expo also reflects the vigor of Shanghai’s elites – advocates of a free economy and an affirmative foreign policy – in contrast with the cautious populism that president Hu Jintao and premier Wen Jiabao represent in Beijing: after all, global governance (from monetary and financial stability to climate change agreements) may perhaps depend on the internal balance in China between the pyrotechnics of Carnival and the vigil of Lent.