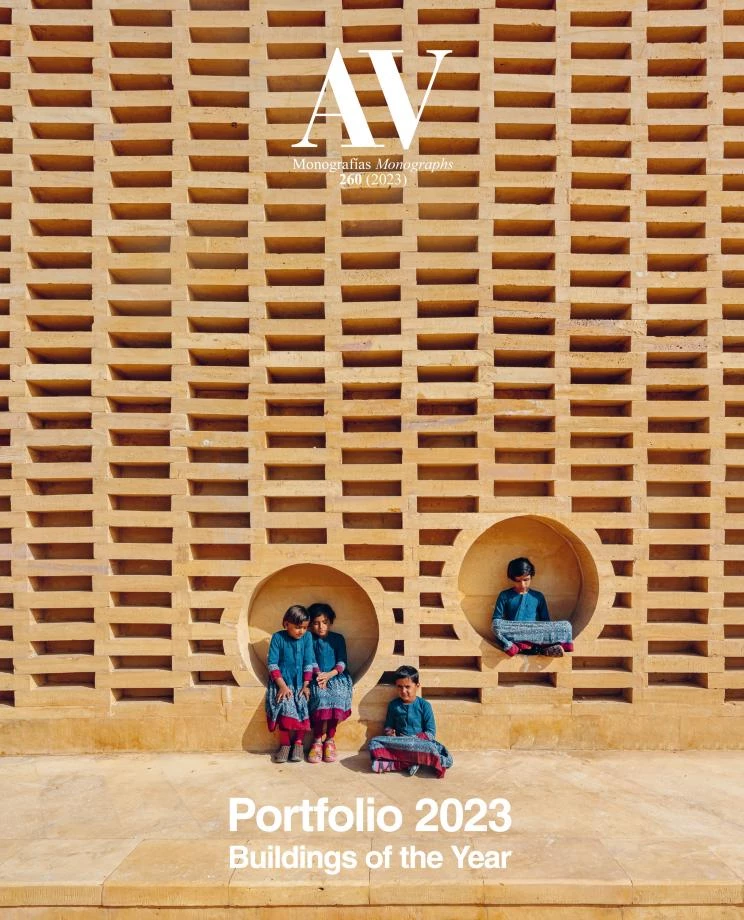

José Manuel Ballester, Primavera, 2015 (fragmento)

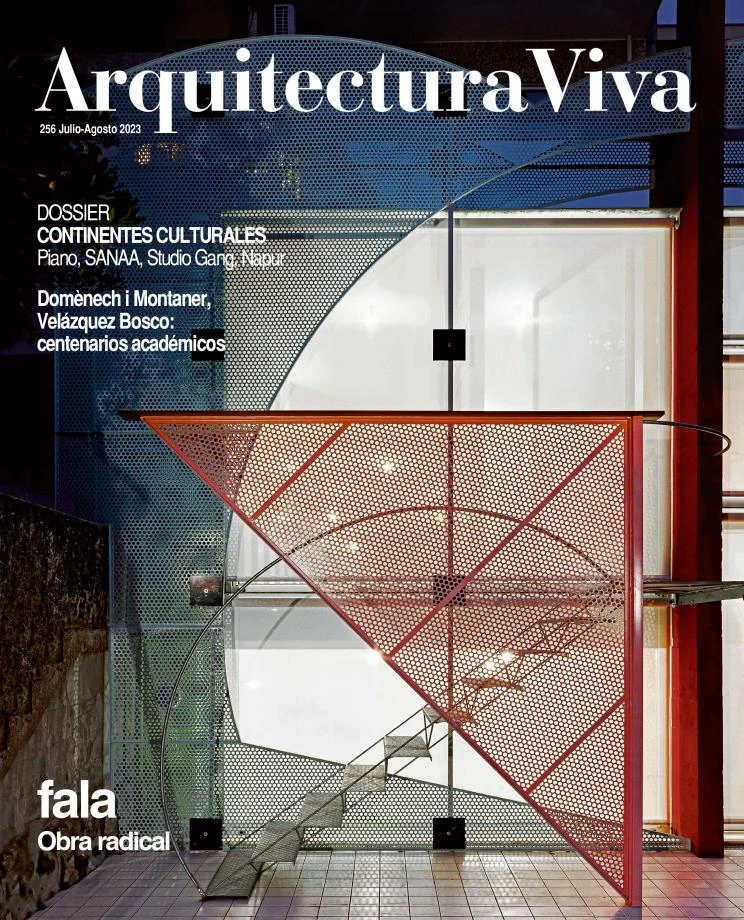

Architecture longs for the exact pleasure of the garden. Photographer José Manuel Ballester – who was already on the cover of ‘Utopías útiles’ with his stripped-down version of The Garden of Earthly Delights – is showing De arboris perennis at the Botanical Garden of Madrid, a project that includes the orange and laurel trees of Botticelli’s Primavera, and that representation of the essential garden reconciles us with the natural world when the good season invites us to enjoy outdoor living. The impressionist plein air exalted the countryside, but in the Renaissance panel fruit trees evoke the mythical orchard of the Garden of Eden, hortus conclusus of quiet joy or pleasant meadow of pagan reunion, and the image without figures challenges us with the colonnade of trunks, a vertical architecture that rises from the flowery grass to the fruit-filled treetops. Behind this domestic nature we imagine a master gardener like the one depicted by Paul Schrader in the film that wraps up his trilogy on redemption, because caring for plants demands penitential attention.

Plant a tree, have a child, write a book: the quote attributed to the Cuban politician and writer José Martí condenses with poetic precision our responsibility to protect life on the planet, ensure the survival of society, and increase the symbolic capital of the species. With the language of science, it suggests contributing to the transmission of information through the genetic channel and through the cultural one, because the reproduction of organic matter is as important as the legacy of knowledge. And if progeny or intellectual production belong to the human sphere, the tree can represent the remaining forms of life, respect for which is essential to guarantee our own survival, and to which we are inextricably tied. Perhaps no one was able to express that link better than Miguel Hernández in his ‘Elegy to Ramón Sijé,’ where the dead friend is transformed into fertile soil so that the poet can write “I want to be the tearful gardener / of the earth you occupy and enrich,” finding final comfort in knowing that “you will return to my garden and my fig tree.”

This essential communion with the different forms of vegetal life certainly lies at the origin of the universal desire for a house with a garden, as much as we know the extent to which sprawl is incompatible with an efficient use of the material and energy resources that enables us to face the critical challenge of climate change. If the compact city is indeed the best instrument to make urban humanity sustainable, and to protect the natural spaces from real estate greed, this does not mean that we should give up green in parks, tree-lined streets, or balcony pots. To enjoy plants, indeed, it is not necessary to believe in the intelligence attributed to them by the Italian neurobiologist Stefano Mancuso; however, just as all of us are holobionts formed by a symbiotic association of our bodies with our microbiota, a forest is in fact a superorganism with a behavior that could perhaps be described as conscience. Be that as it may, “il faut cultiver notre jardin”: the Voltaire of Candide speaks a language that we architects understand.

Paul Schrader, El maestro jardinero, 2022