Barragán in Black and White

The Mexican master’s centenary invites to soberly remember an oeuvre whose present popularity is overly associated to the chromatic brightness of his walls.

A pink facade, a yellow lattice, a violet wall: the work of Luis Barragán abounds in rugged textures and fiery colors, a surprising mix of tactile roughness and visual violence accompanied by a parallel devotion to Franciscan austerity and oriental sensuality. Such efficient sensorial oxymoron, however, hides behind its chromatic gleam the es-sential laconicism of houses and gardens that aspire to construct paradises by means of stripping, in a mystical and erotic itinerary that glides from the murmur of fountains to the silence of ponds. If we contemplate Barragán in black and white, the artistic and vital trajectory of this refined Catholic gentleman becomes at once more transparent and more hermetic, more annoying in its self-absorbed creolism and more disconcerting in its stubborn finds, more trivial in its archaic exoticism and more profound in its timeless convictions.

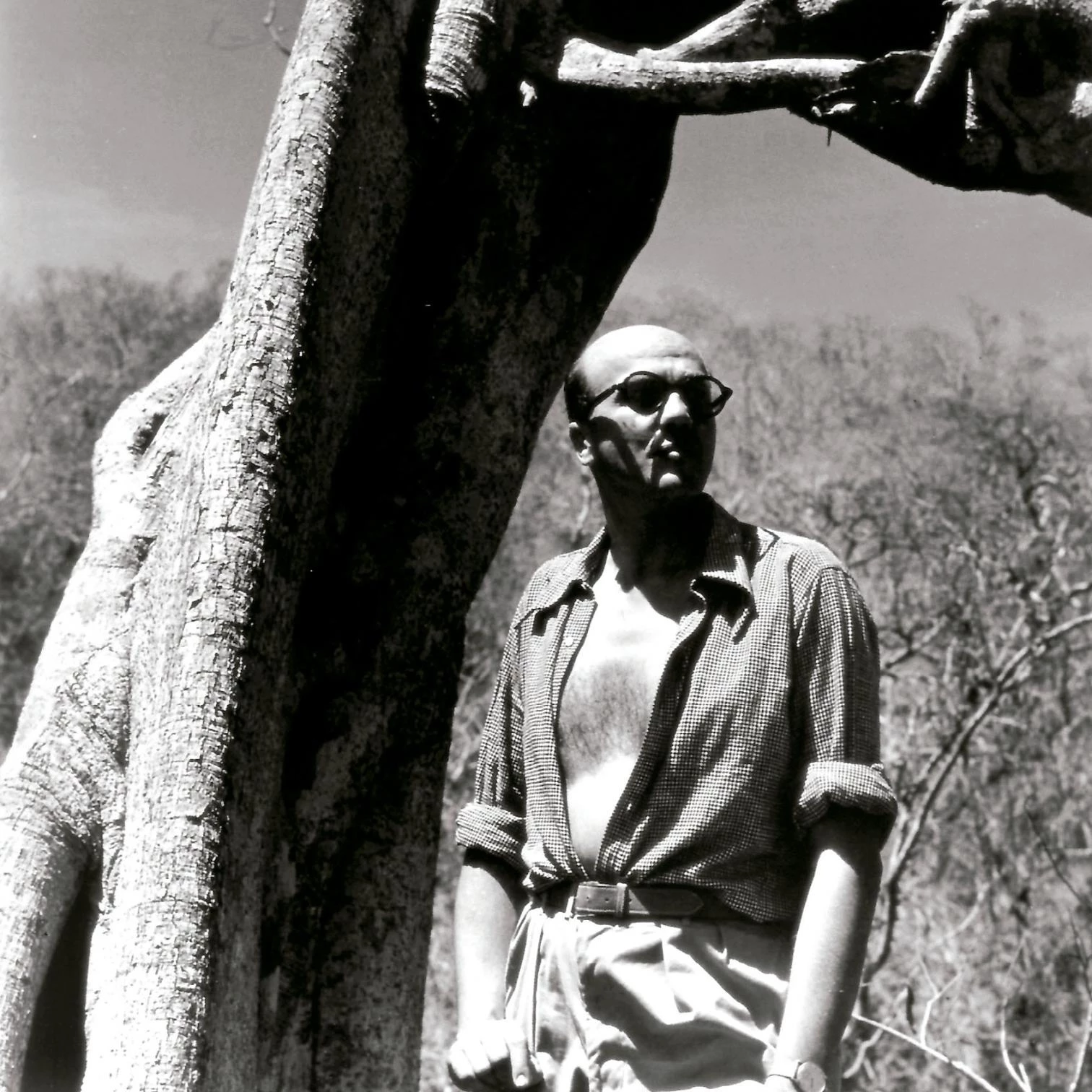

Scenario of his childhood, the dry Sierra del Tigre in Jalisco is the starting point of a career which was determined by the discovery, in an early trip to Europe, of the Islamic gardens of Spain and those of Ferdinand Bac.

Ever feeding on the nutritious humus of a background of haciendas and horses, some have seen in the architect Barragán a reflection of the writer and photographer Rulfo, both having roots in the arid geographies of the Tigre range, in the south of Jalisco. But while Rulfo perceives the desolate terrain as the scene of an anthropological and collective drama, Barragán appropriates the vernacular landscape for himself, making it the setting of an individual, lone exploration. After completing his studies in engineering and architecture, during the European trip that was a must for scions of affluent Latin American families, the young Guadalajaran discovered in the Islamic gardens of Andalusia a dream of harmony that seemed in tune with the innocent nature of his childhood, and in the decadent Mediterranean gardens of Ferdinand Bac he found a promise of happiness that jived with the traditional constructions of his native land. By the time he returned to Mexico in 1927, the architect had traced the solitary road that would return him to the gardens and ranches of his boyhood.

In the houses that Barragán built in Guadalajara before his definitive move to Mexico City in 1936, his regional sensibility was not removed from the neocolonial architectures that were common in California or Florida at the time, from the sober, whitewashed, mission-style hermetic walls to the exuberant gardens and intricate latticeworks of ‘Spanish’mansions. Nevertheless, it is clear that he was beginning to mumble in a language of his own. But the next four years in the capital showed the architect trying to reconcile himself with modernity at its most superficial and mercantile, the result being a handful of mediocre, pragmatic buildings. This was a detour in his progress that would be corrected only by his decision, in 1940, to cease working for third parties. From then on his activities would be limited to developments of his own, through an efficient formula that joins architect and client, and was to give Barragán his greatest professional triumphs and happiest artistic achievements.

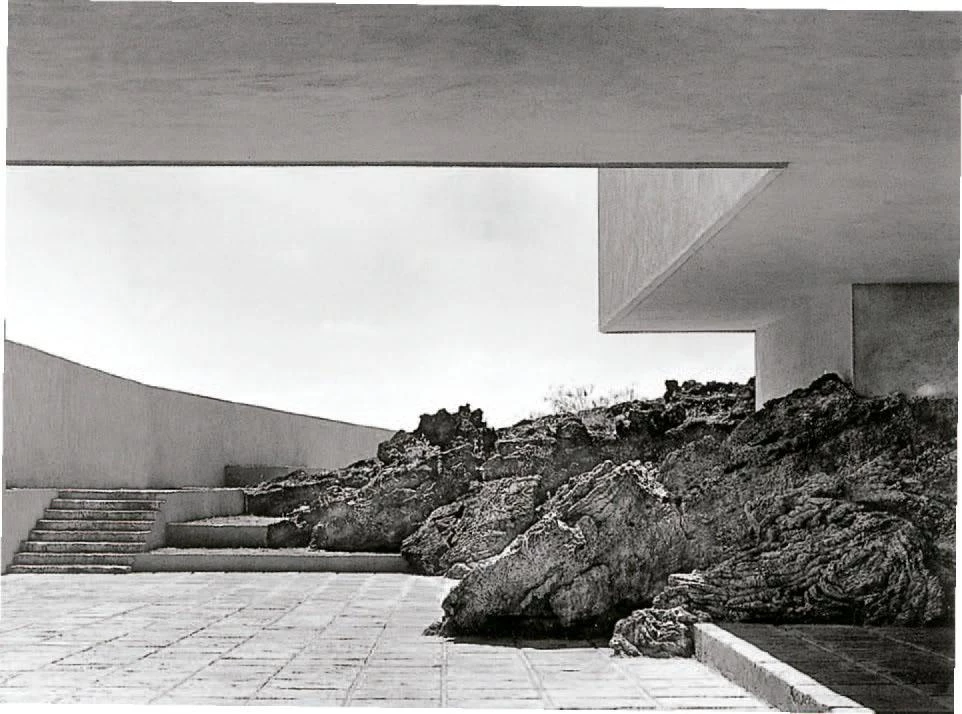

As an architect of fraccionamientos – parceled urbanizations where the developer designs streets, squares, and fencings – Barragán acquired terrains and drew up colonies in which he built gardens and ornamental pieces, an at once economic and esthetic activity that would culminate with his great landscaping works: the volcanic gardens of El Pedregal in 1945-1952, the avenues of ash and eucalyptus trees of Las Arboledas in 1957-1963, and the fountains and equestrian paths of Los Clubes, undertaken from 1965 to 1968. Three developments characterized by an exquisite serenity, built with geometry, vegetation and silence, where the grave material of the constructions strikes a contrast with the vicissitudes of the topography, the caprices of botany, and the imprecise flappings of breeze, birds or water. Alas, all are now defaced, but their oneiric and placid spirit survives, intact, in period photographs, which give off a perfume of immobile perfection and quiet solitude.

Barragán bought land on Mexico City’s outskirts and built condominiums where his large landscape works materialized. The volcanic gardens of El Pedregal (1945-1952) introduce geometry in a haphazard topography..

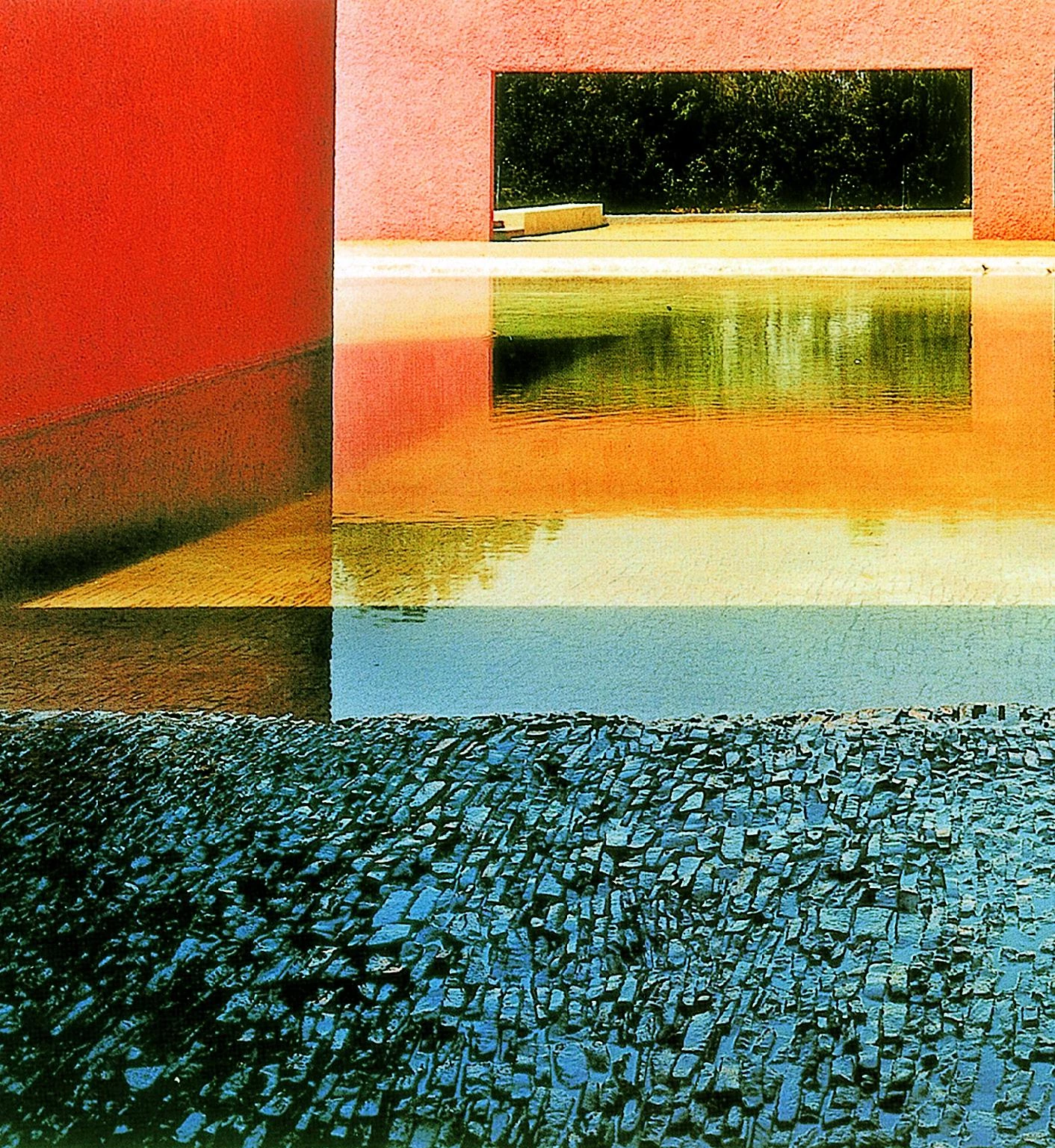

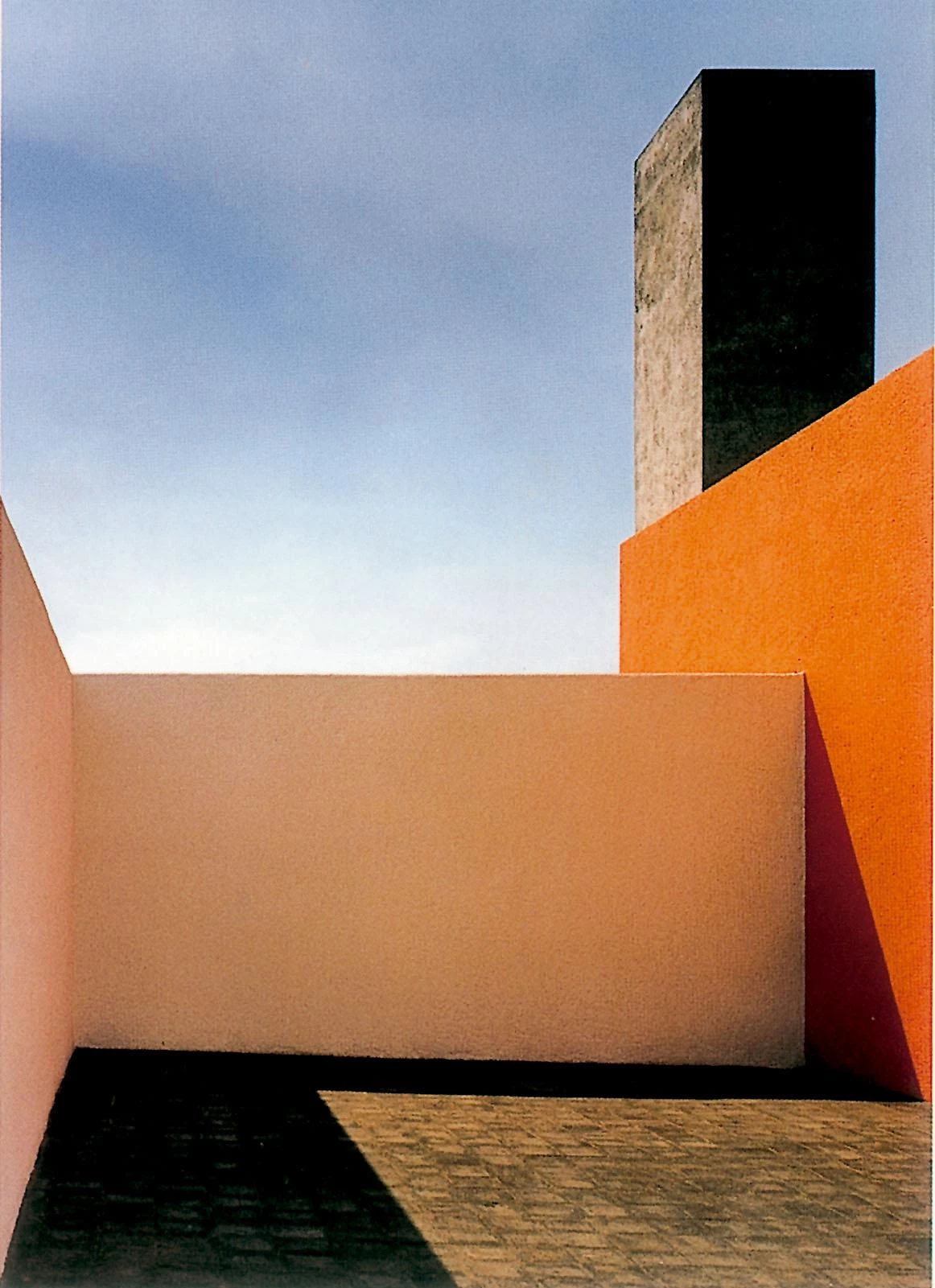

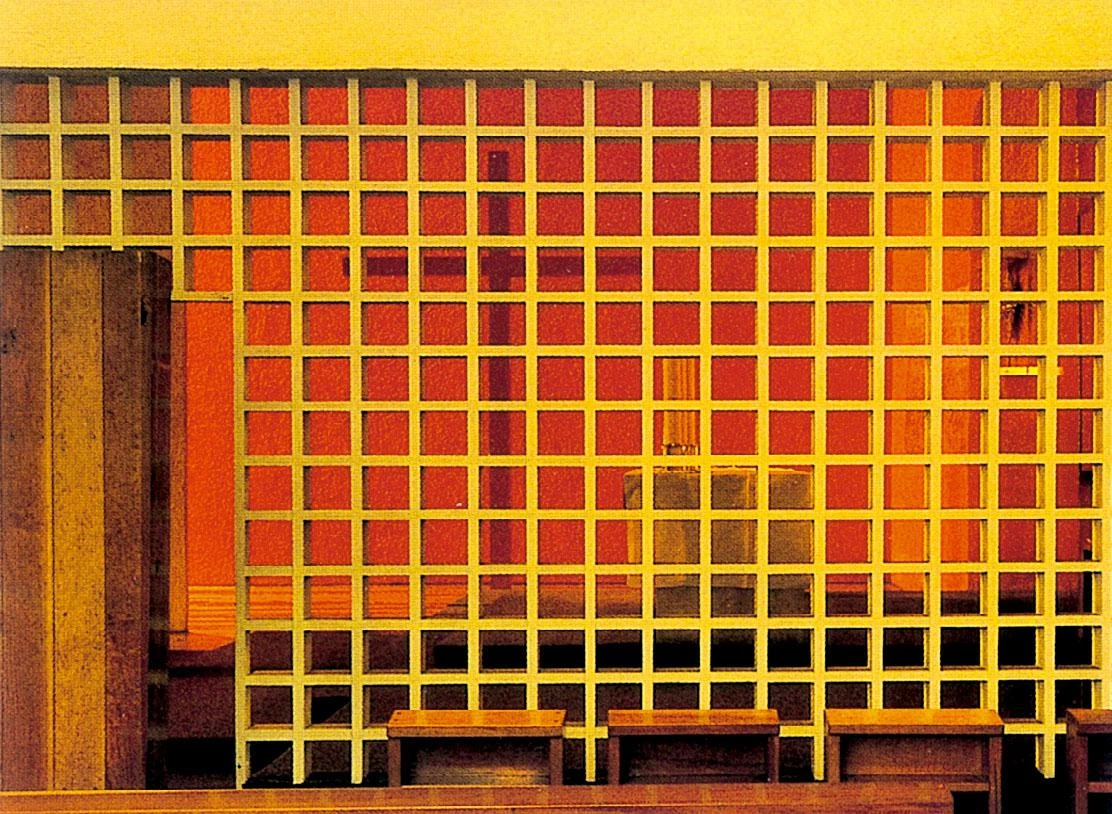

The same combination of monumentality and intimacy is present in his few works of those years: his own house and garden in Tacubaya, of 1947, a poetic, primordial, and labyrinthian autobiography that the writer Elena Poniatowska called a “one-monk monastery”, with mythical episodes such as the wood staircase that folds weightlessly, the large window divided by the mullions of an aerial cross, or the roof terrace transformed into a secret courtyard of hermetic and vibrant walls; the Capuchin nun convent, of 1952-1955, where the new chapel and the preexisting building, remodeled, are lit by an amber gleam and the changing reflections of the pool with petals of the patio, a premise of rigor and rapture cloistered by lattices and stained-glass; and the San Cristóbal stables, of 1967, a horizontal precinct of pink walls, orange fountains and green ponds for the slow choreography of horses, which recreates in Mexico City’s outskirts an old Arcady, the family ranch where Barragán had grown in com-munion with colts and landscape.

An orange terrace wall, a yellow latticework or a pink perforated front: the sumptuous colors and rough textures of the architectural oeuvre –from his own house in Tacubaya (1947) to the chapel and convent for the Capuchinas (1952-1955) or the San Cristóbal stable (1967) – sum up the legacy of Barragán. However, that chromatic brightness conceals his progressive ascetic relinquishment, in search of timeless expression.

In both fraccionamientos and constructions, the architect benefitted from the cordial support of three singular retinas: that of the Guadalajara painter Chucho Reyes, who became a friend at the time they both settled in the Mexican capital, whose playful and eccentric vernacular colors inspired the rare tones of Barragán’s walls; that of the sculptor of European origins Mathias Goeritz, collaborator in numerous projects from 1949 onward but from whom he would have a falling off with in 1957, in the wake of conflicts involving the credit for the Ciudad Satélite towers, colossal landmarks of sharp geometry that were used as advertising sign for an urban development; and that of the landscape photographer Armando Salas Portugal, privileged in-terpreter of Barragán’s work from the time they met in 1944 up to the architect’s death in 1988, without whose fascinating images it would be impossible to explain the international popularity of Barragán, who had as milestones his 1965 collaboration with Louis Kahn in the Salk Institute, a 1976 exhibition organized by Emilio Ambasz at New York’s MoMA, and the concession, with the backing of Philip John-son, of the 1980 Pritzker Prize.

Such unanimous fame, which in the past decade has given rise to a deluge of publications, the acquisition of his archives by the designer furniture manufacturer Vitra, and an itinerant exhibition that has been tirelessly spreading the Barragán gospel throughout the world, has also produced a tiring proliferation of colorful walls that incubates the germ of reaction. Barragán could come to be seen as a nostalgic landowner of the old regime, of skin-deep culture and scant drawing talent, who succumbed to the influence of the withered orientalism of a Belle Époque garden designer, and who dedicated himself to developing residential precincts for the rich and building neocolonial houses furnished with the conventional tastes of a decorator of coutry estates and luxury hotels. And indeed the insufferable triviality of his reading notes, the mystical tweeness of his interiors bathed in a golden and indirect light, and the folkloric scenography of his houses adorned with earthenware jars, riding seats, baroque angels, indigenous altarpieces and iron candelabras begin to numb our capacity for criti-cal discrimination, threatening to bury the Mexican master’s genuine genius under a pandemonium of visual and literary garbage.

In the end, Barragán’s transcendence surely has to be found in his reticent resistance to the noisy and accelerated mechanization of the contemporary world, not so much in an alleged and probably fallacious combination of modernity and tradition as in the voluptuous cultivation of a reflective asceticism that formulates an amendment to the entire modern project. Despite his evanescent estheticism and his vaguely metaphysical spiritualism, in the willowy figure and noble bearing of Don Luis one discerns, in the words of anthropologist Alfonso Alfaro, a secret fraternity with the Pasolini who was aware that “one reaches ultimate truths only through the purity of the bodies and the senses.” It is that same Barragán who judged it an error to have exchanged the protection of walls for the exposure of glass, and who dedicated his life’s work to rectifying this mistake of modernity.