Gull Rainbow

The technological populism of the new Barajas terminal is a symbol of the economic thrust of a political period that ended with the general elections held this month.

An airport evoking flight is almost inevitable. From Saarinen’s TWA to Calatrava’s Sondica stretches a long tradition of bird-shaped terminals. But the profile of the new Barajas resembling a flock of gulls seems so timely that it will be hard not to make ironic comparisons with the logo of the Popular Party. What is to be Madrid airport’s Terminal 4, however, deserves to be the architectural symbol of José María Aznar’s prime ministership for more substantial reasons: the formidable amount of money invested, a total of 2,440 million euros if we include the two new runways, the whole project executed in the course of his two mandates, which have been characterized by sustained material growth; the technological image of the work and its character as a threshold open to the world, appropriate features to represent a period of modernization and globalization of the country’s economic and social structures; and last but not least, the localization in the Spanish capital, reinforcing its centrality in the transport network and efficiently expressing the will to use Madrid as mortar in the face of the centrifugal tensions of the periphery.

On a more anecdotal plane, Aznar’s friendship with Tony Blair and Blair’s friendship with Richard Rogers, author of the terminal along with the Madrid office Estudio Lamela, closes the circle of the Anglo-Saxon connection that has shifted Spanish foreign policy from the Franco-German core of old Europe to the North Atlantic connection that was staged in the Azores. In any case, the new Barajas is born to become the great hub of traffic between Europe and the South Atlantic, enhancing the airport’s role as a junction for communication with Latin America, and now that it can accommodate 70 million passengers per year, it will be possible to express through physical flows the economic ties that link Spain’s financial and corporate fabric to that of America’s major countries: a transatlantic presence of the Spain of ‘new conquistadors’ that made it to the cover of Time magazine on 8 March, and which along with the economic strength, global modernization and reactive centralism that are symbolized by the airport, made Barajas the best scenario for Aznar’s farewell on 13 February.

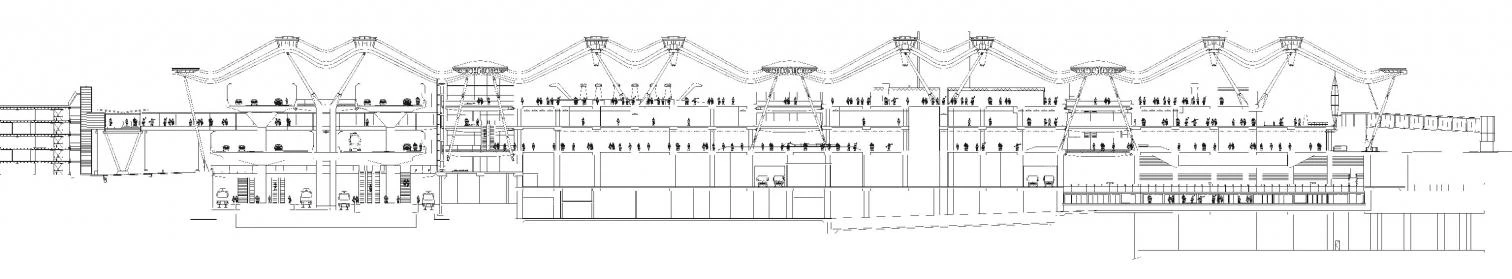

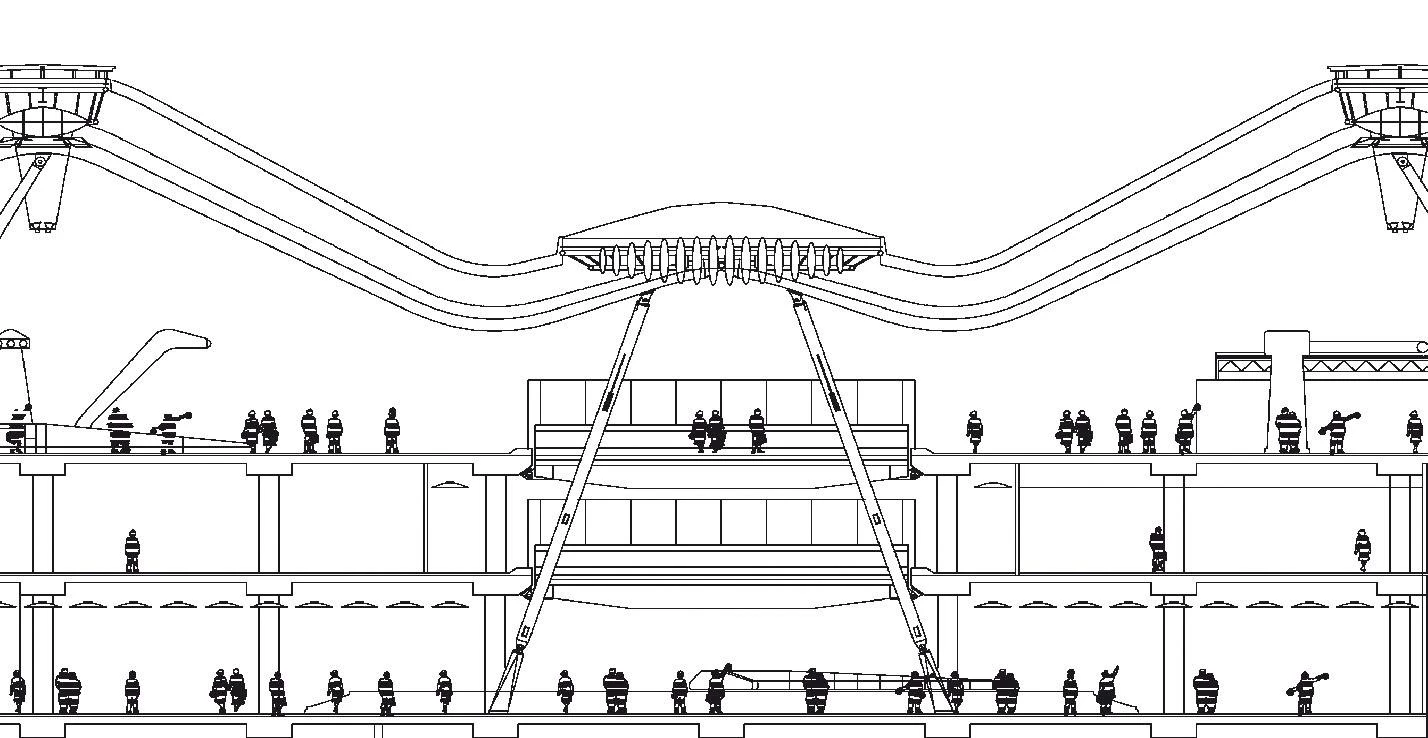

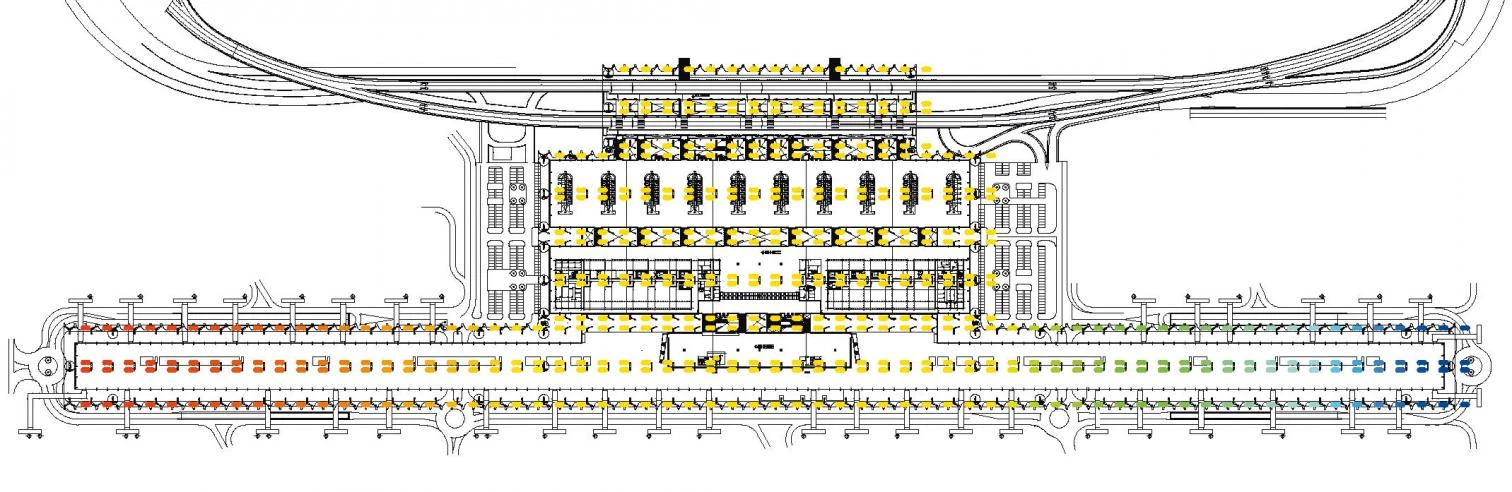

Although the planes will not fly until August and the terminal is only expected to be fully operational in 2005, the civil work is essentially finished, less of seven years since Rogers and Lamela won the competition: a record time considering the magnitude and complexity of the job. Seven large construction firms organized in temporary alliances (and up to 776 subcontractors, according to trade unions) have carried out 1.12 million square meters distributed in three buildings: a parking lot for 9.000 cars, a main terminal stretching 1,142 meters, and a satellite terminal with a length of 927 meters, these connected under the runways by an automated train and between them giving access to 84 boarding gates. Like the transit docks and the check-in segments, the baggage claims and the checkpoints, the two huge longitudinal dikes are organized on different levels under the roof shaped like a bird in flight, which supports its repeated waves with a tree-shaped structure of concrete and steel (arranged in accordance with a 9 x 18 meter grid), and allows natural illumination through the skylights in the ridges and the canyons of light that gape open between the gulls’ wings.

Inaugurated by Aznar at the end of his term, when it was not yet operational, the new terminal of Barajas airport is a luminous and optimistic work that supports the roofs of bamboo strips with steel branches.

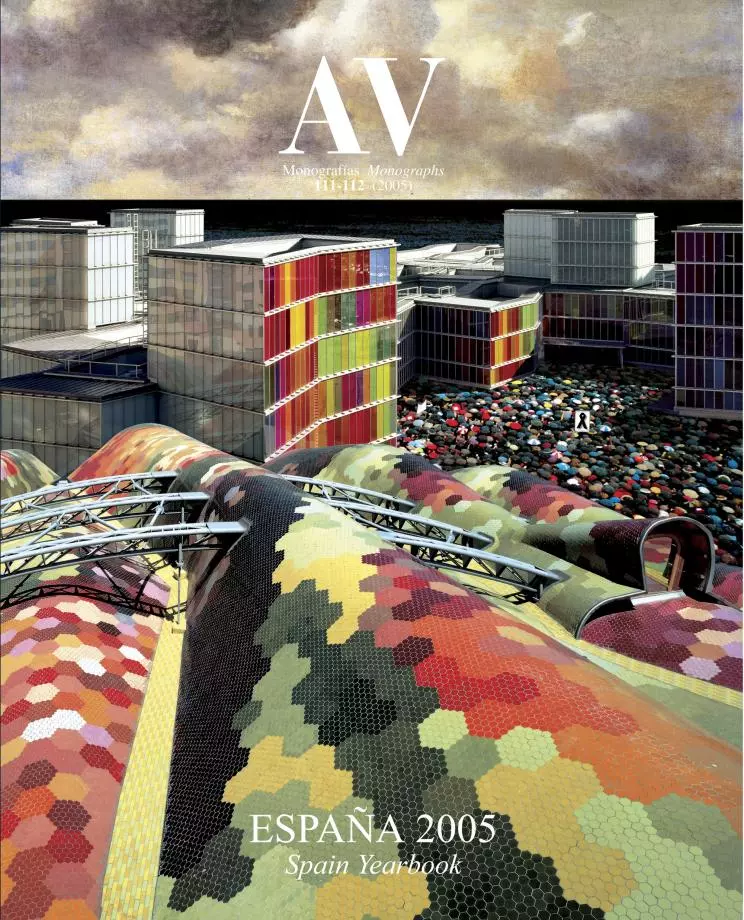

The endless multiplication of modules, which in the original project formed an extruded roof, is alleviated in the definitive scheme by a sequence of mounds that dissimulates execution imperfections and gives a pleasant waving movement to the warm interior lined with bamboo slats, even if at the cost of having to remove rainwater through an intricate pumping system, since the section hinders the usual gravity-based system of evacuation. Moreover, the monotony and disorientation of buildings a kilometer long is lessened by the polychromy of the structure, which, while maintaining the yellow color typical of signage or public works machinery in the central zone, takes up all the colors of the rainbow as it stretches out: an unexpected and perhaps questionable decision in view of how the easy harmony of the concrete, glass and bamboo with the quiet yellow of the middle volume becomes shrill at the ends of the dikes, although one could of course argue that such coloring – taken from kindergartens or television program sets – helps orient the passenger, is popular for its immediate legibility, and in any case will dissolve in the clutter of shops that irremediably ends up colonizing terminals.

In order to make this huge building more user-friendly, the structure of the terminal has been painted in the colors of the rainbow, hoping that this chromatic diversity will help as well with the orientation of passengers.

In Barajas, the smiling lip or bird profile is held up by steel branches that fork out naturally, and the warped roof rests on them like a thick floating carpet, one more rigid than a canvas but lighter than a slab. Such lightweight elegance perceptively justifies the structural extravagance of the supports and turns the interior into a bright and tidy forest that is attractive in a special way, penetrated as it is by deep-set canyons that reveal with a spatial richness the superposed complexity of the section, with the underground trains, the dizzying ribbons transporting luggage, the baggage collecting belts, or the check-in counters. Still spared the invasive irruption of furniture, shops, and checkpoint screens, the buildings flaunt their defects like a face under spotlights, and the design inconsistencies that result from a rush job reveal themselves with a clarity that will blur the hustle and bustle of occupation and use. In this way, the abrupt downspouts along the central axis, the ventilation ducts that rise perpendicularly to perforate the roof, the service modules that oppressively approach the supports, or the disconcerting paleo-industrial design of the structures that sustain the escalators and the capsule-like elevators have a visual prominence that will vanish with crowding and routine.

This colossal, admirable project (Lamela’s most important so far, and also Richard Rogers’, along with the Pompidou and Lloyd’s) suffered in the opening ceremony the mediatic competition of three large bronze sculptures by Manolo Valdés engraved with poems by Mario Vargas Llosa. Acquired to decorate the terminal by Minister Francisco Álvarez-Cascos, through the gallery Marlborough and for a bit over a million euros, they got more attention in some dailies than the actual building. The so-called ‘Three Dames of Barajas’, however, are only routine monumental heads of late-pop imagery that make one long for the Botero piece in the current terminal, and the lyrical monologues inscribed on the countenances of The Dreamer, The Flirt, and The Realist are so ridiculously schmaltzy that we can only hope they are products of a slip or a joke. But maybe the mandate of the outgoing premier is adequately represented as much by the firmness, ambition, and pragmatism of this construction as by the triviality of its symbolic core.