International Bamboo Architecture Biennale

A Low-Tech Experiment

Xitou Village, hidden in the green hills and clear waters of Baoxi Town, Longquan City (Zhejiang Province), is one of the birthplaces of the Celadon ceramic culture. Inconvenient transportation somewhat shields it from the influence of rapid urbanization, hence reserving its integrity and primitiveness in both geographic environment and cultural ecology.

This reclusive village has finished a low-key rural construction experiment. From August 2013 through August 2016, eighteen bamboo constructions were seen rising above the land and constituting the China Longquan International Bamboo Architecture Biennale. Architects from nine countries participated in the event: Li Xiaodong and Yang Xu from China; George Kunihiro from the United States; Simón Vélez from Colombia; Anna Heringer from Germany; Mauricio Cárdenas Laverde from Italy; Kengo Kuma and Keisuke Maeda from Japan; Wise Architecture from South Korea; Madhura Prematilleke from Sri Lanka; and Vo Trong Nghia from Vietnam. Referring to this bamboo construction experiment, Ge Qiantao, curator of the event, stated: “The idea of the Bamboo Architecture Biennale has its root in our concerns about current phenomena in rural areas in China including the decline of vernacular culture, rural poverty, and increasingly sharper contradictions in the urban-rural dual structure, etc. The problem of gradual homogenezation in the urbanization process is equally prominent and has rapidly eroded towns and villages.”

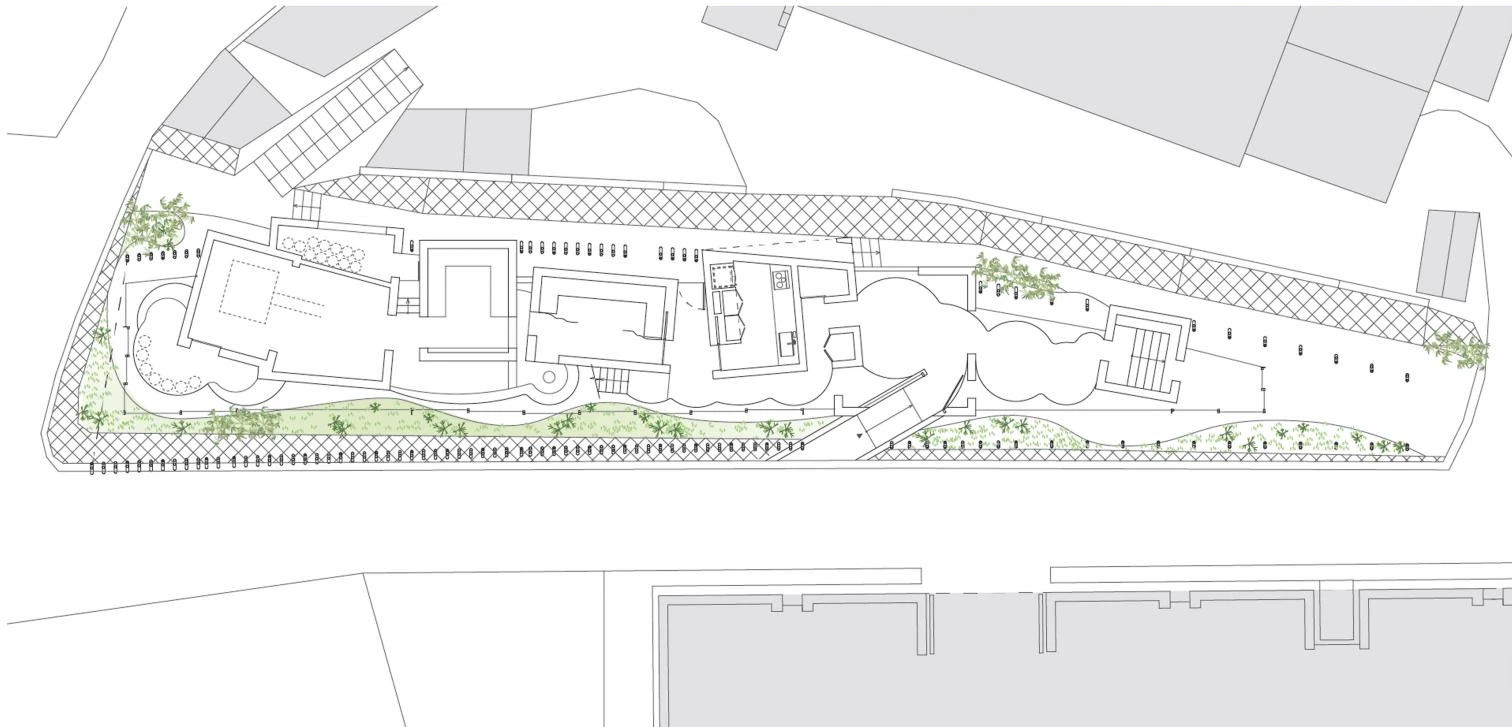

Built along the natural extension of a terraced field from east to west, the site enjoys a unique natural environment. Facing the river to the west, it is adjacent to the old street that connects Xitou Village with the terraced field in the north and the cement road that links the village with the exterior in the south. Across the river sits the original traditional village. The river and a white wall built along the west bank separated the site and the existing village spatially, which keeps the two parts with different architectural styles and independent entities.

The eighteen buildings are divided into three groups. Based on the natural contours of the terraced fields, the buildings are connected together on different levels. Although the buildings in the site are varied in shape and free in organization, hence lacking echoes with each other, we can still find the designer’s considerations for the traditional village environment. For instance, as the road by the south of the site is the main road to enter the village, buildings near the ‘entrance’ have freer shapes, larger volumes, and stronger visual impact. As for the north area of the site, closer to the original village and connecting the old street, the buildings there have humbler and simpler shapes and maintain a scale and texture similar to the adjoining traditional dwellings.

A Repertoire of Solutions

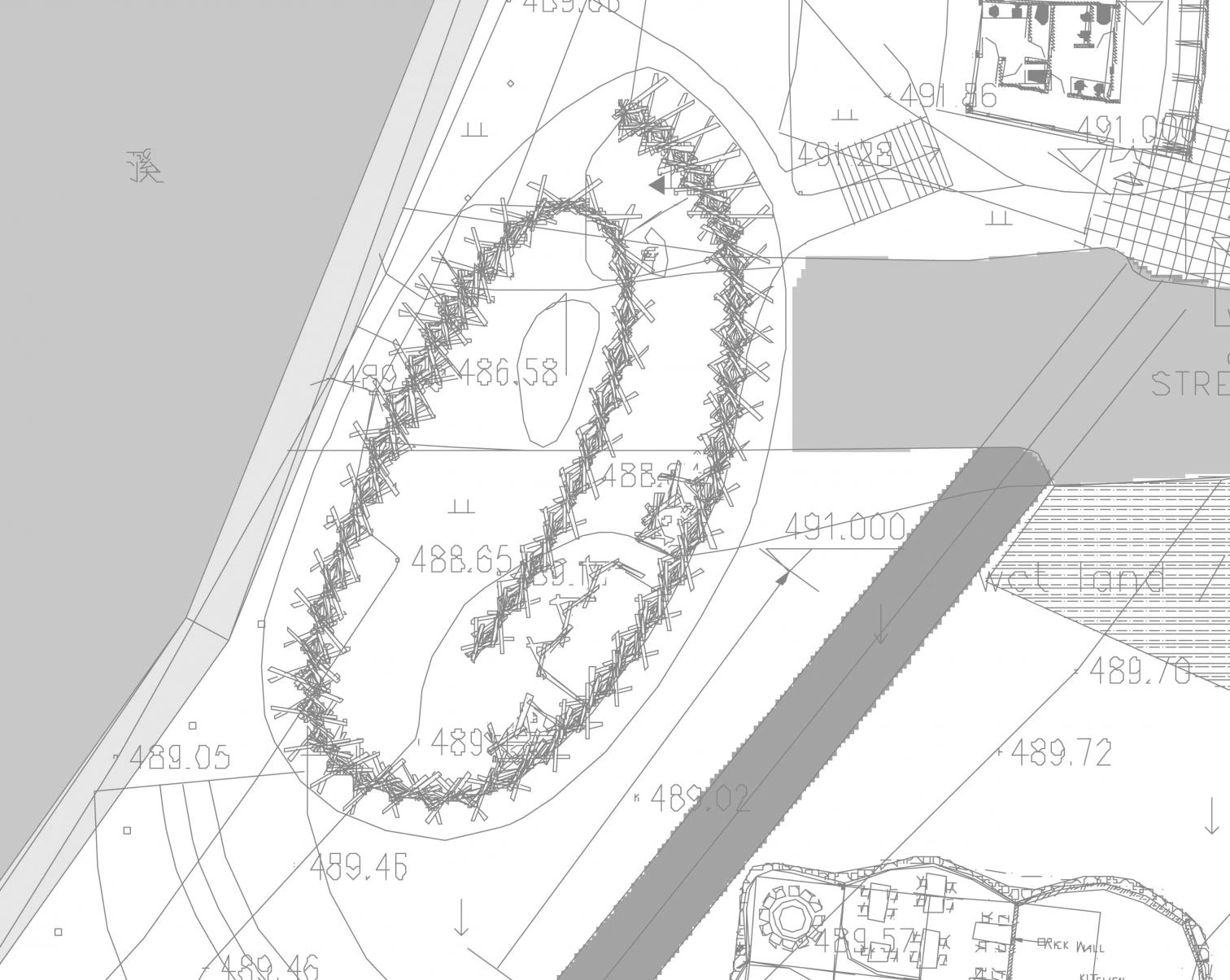

The Double Helix Bridge by Ge Qiantao consists of a special bamboo cover on the original stone bridge. Connecting the existing village and the Bamboo Architecture Biennale site, it is regarded as a dialogue between the ‘traditional age’ and ‘present time.’ The architect chooses a dual-spiral gene arrangement map as the formal language, with an implication that the village shall “walk into the future along the local cultural genes.” Bamboo sticks laminated from strand bamboo are arranged to mimic the genetic arrangement and fixed onto the stone bridge with small metal ribs, hence making the bamboo cover a combination of enclosure, window, and ceiling. Some bamboo chairs are placed on the bridge to turn it into a public space for people to stop and rest.

Adjacent to the original dwellings, the ceramist’s workshop by Keisuke Maeda is a rectangular structure consisting of sitting rooms and a multifunctional studio. During construction, the architect makes full use of the local method and builds a bamboo-reinforced earth wall with bamboo and earth, which can also be addressed as a low-tech version of a reinforced concrete wall. In addition, he installs a bamboo grille on one exterior facade, hoping it will resonate with the natural surroundings.

For its part, the traditional ceramic workshop by George Kunihiro is a rectangular bamboo building. The interior space is divided by earth walls, and the roof and structural elements are made of bamboo. Furthermore, the architect used fired clay fragments for the paving, a solution that was later abandoned when Celadon ceramic started to be used in the region, but that has a special color and texture, and that, with the architect’s design and reformation, can become a unique building material. This not only enables a cyclic use of fired clay, but also endows the building with the connotation of ceramic culture.

The reception Center by Vo Trong Nghia is a curve-shaped construction built with three bamboo elements: bamboo sticks of equal size and similar thickness; small bamboo splices joined to continuous structures; and interlocked vertical and horizontal arch trusses. It makes the whole structural system complex but logical at the same time. This building, from the shape and structural design to the detail treatment, which develops the typical features of bamboo, offers a stronger sense of wholeness compared with other buildings in the Biennale.

Kengo Kuma was in charge of the design of the Contemporary Celadon Ceramic Art Museum and a public washroom nearby. Originally, Kuma intended to use heavy bamboo to build both buildings, but later he chose to use wood in the Art Museum and heavy bamboo in the washroom. Both constructions share a similar building logic. Through the dislocation and overlapping of heavy bamboo and wood pieces, he managed to build a continuous curved wall with many small openings, which enhance the mobility of space.

Bamboo is also the main material used in the Bamboo Dock Restaurant and the Children’s DIY Workshop by Wise Architecture, but the bamboo is so well wrapped that not any clue of bamboo can be found from the outside. The main structure of the restaurant is a nine-patch steel frame, where curved bamboo sticks grow horizontally, constitute various curved surfaces, and are covered with a nearly white fiber skin along the interior walls and roof. With this low-cost construction method, the architects wanted to create a sense of ‘scattered mountains.’ However, a clear concept may not yield a clear result. The final building is not very satisfactory.

Another building is the low-energy Bamboo House by Italy-based Colombian architect Mauricio Cárdenas Laverde. The project explores how to achieve the maximum possible reduction of carbon emissions and makes the most of natural local conditions such as sunshine, water, and plants. Dividing the architecture into several similar space units, the architect uses bamboo, earth, and other natural materials in the building process. Bamboo is used as the structural system.

The Boutique Hotel is a project by another Colombian architect, Simón Vélez, a leading figure in bamboo construction (see Arquitectura Viva 138). Built on a mountain, the support columns of the hotel change in length to adapt to the terrain, but the cement piers at the bottom maintain a uniform height. The hotel is composed of two circular volumes. Bamboo sticks outline the roof profile and form natural eaves. Celadon piles are laid on the dome-shaped roof.

The Creative and Innovation Center is designed by the Chinese architect Li Xiaodong, and is similar to his Liyuan Library (see Arquitectura Viva 151) in both shape and construction logic. Both designs adopt a neat rectangular form with a grid framework, a glass curtain, and bamboo grille skins.

The planner of the Bamboo Architecture Biennale site, Yang Xu, designed two Art Hotels. One is ‘Hua Jian’ (Waterfront Hotel), built along a stream. With helical planes, the architect lifts every guest room to different levels. His inspiration comes from ancient dragon kilns. The other is built against cascading fields. Like a blooming flower with four petals in bird’s view, it is named ‘Hui Jian’ (Flower-field Hotel). The architect used bamboo, old bricks from the local kiln, earth, clay, and concrete in this building. The combined use of both original and processed bamboo, and the contrast between the bricks and clay and the mixture of natural stones and traditional earth walls reflect the diversity and irregularity of the architecture.

The Youth Hostel by Anna Heringer (see AVProyectos 61 y Arquitectura Viva 196) is located at the entrance of the site, covering a larger floor area than other buildings. It consists of three individual buildings, all of which are built with rammed earth walls at the center and with a light bamboo-woven mesh as external envelope. The guest rooms are surrounded by the rammed earth walls, and the semi-open space between the earth walls and the bamboo-woven structure functions as a public space. Openings of irregular shapes on the earth walls bring in natural light. In the Youth Hostel, the lower third of the rammed earth walls is built with stones, while the two upper thirds are completed with earth. Walls built with this method can be found everywhere in Baoxi. Outside the Hostel, the bamboo meshes make dappled reflections on the walls. Strictly pursuant to the Biennale requirements, local materials including bamboo, earth, and stones are fully used in this project. The bamboo-weaving process is inspired in the local rattan baskets, and the earth wall construction technology is based on the local building methods, but improved with the use of modern industrial materials. These practices integrate local culture and building technology into the architecture, hence working out a bamboo architecture that has a sense of belonging.

Form, Construction, and Rural Life

The Bamboo Architecture Biennale fully interprets the concept of “the spirit of place and rural construction” through a genuine construction process in which bamboo is chosen as the ideal material. Some architects chose bamboo directly for the main structural elements, and others used bamboo on the envelopes or facade decorations. In addition to bamboo, the architects also used other traditional materials like rammed earth and ceramic. During the construction process the architects paid great attention to the bamboo processing and local traditional construction methods, as well as to the direct engagement of local workers. While emphasizing the locality, each architect, more or less, expressed his or her respective design styles. In general, the Bamboo Architecture Biennale presents different ways of reinterpreting the local environment and construction, exploring new forms of understanding rural construction.

Actually, these new bamboo architectures and their original environment reflect two different levels of integration: the spatial one, which can be reached through the design and construction methods; and the integration on a life level, aiming to integrate the finished buildings into the original life and production orders without turning them into mere scenic spots independent from the original environment. This type of integration is related not only to the design, but also has to do with management and operation. In this sense, such low-key rural construction experiment has just begun.

Zhang Xiaochun and Li Xiangning are professors at Tongji University in Shanghai (China).