Asian Vertices

Two skyscrapers in Dubai and New Delhi compete for the world record, while a pyramid in Kazakhstan aims to be a symbol of ethnic and religious unity.

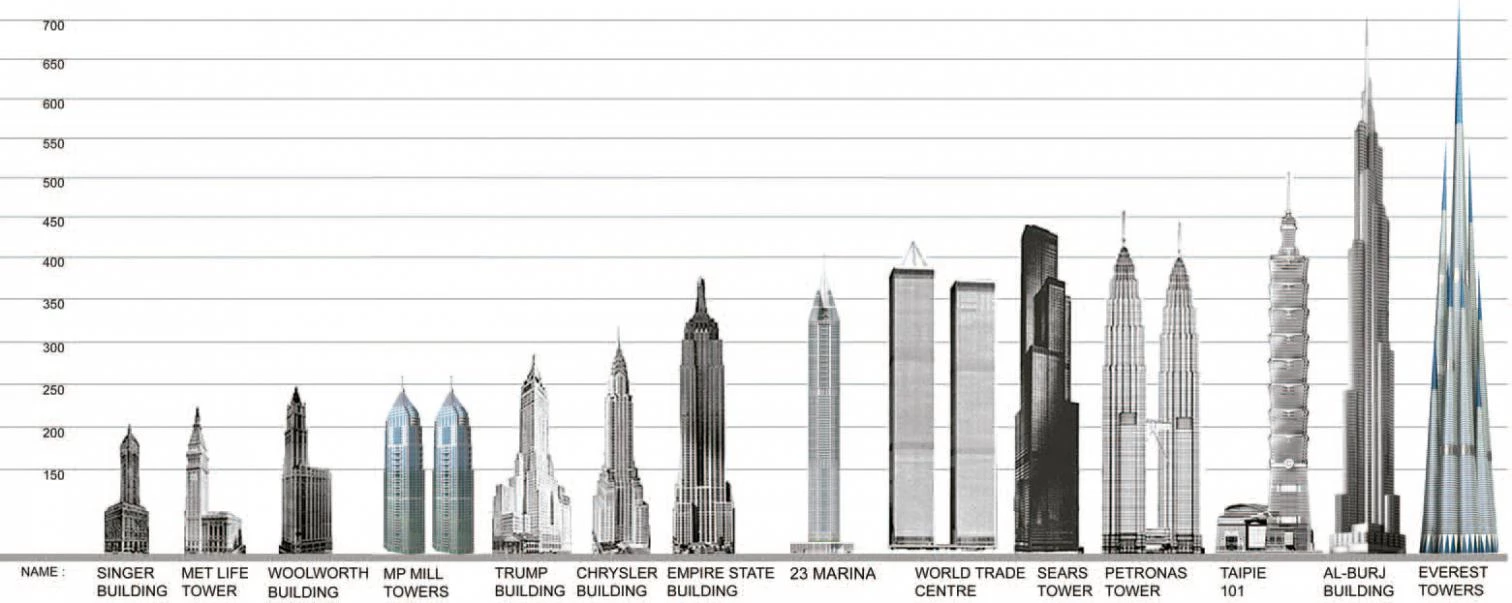

Hindus and Arabs fight to beat the Chinese, who are now ahead of the Malays: for some time now, the world height record will be an Asian league. The 452 meters of the Petronas Towers in Kuala Lumpur were overtaken last year by the 508 of Taipei 101, shifting the world’s ceiling from Malaysia to Taiwan, and even with the 512 of the World Financial Center in Shanghai still under construction, two new Asian aspirants have emerged: the Burj Dubai, a skyscraper designed by Adrian Smith – of the Chicago office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill – in the emirate of the same name in the Persian Gulf; and the Noida, a tower being carried out by the Indian firm of Hafeez Contractor in a satellite city of New Delhi. The height intended for the former, scheduled to be finished in 2008, is 705 meters, although the Arab developers have avoided confirming the figure, simply asserting that the building will beat the world record in all four recognized categories. The hypothetical height of the latter, completion of which is set for 2013 – although construction has not yet begun –, is 710 meters, the express purpose being to bring the mythical record to India. The altitude contest is no longer confined to Asia’s Pacific coast, but has the entire continent for a theater.

After the Petronas and Taipei 101, the two last towers guarantee that Asia keeps the record in height.

The shift away from the Pacific Ocean, or perhaps simply the modification of the aesthetic climate, seems to have had architectural effects, because whereas the two last holders of the record worked around forms close to postmodern historicism, such as the Islamic patterns of the Petronas Towers or the vertical pagoda of Taipei 101, the current challengers are rather inclined toward neo-modernism or hypermodern futurism. Just as the Dubai needle speaks more of the tapering New York colossi drawn by Hugh Ferriss in the twenties or the mile-high skyscraper dreamed by Frank Lloyd Wright than of any Arabian vernacular, the grouped cornets of the Noida translate Norman Foster’s cone-shaped Millennium Tower into the language of comics and cartoons, formulating a hybrid of Snow White’s castle and Flash Gordon’s ship without a link to Hindu tradition. In any case it is hard to say which is more depressing, whether the mildly vacuous expressionism of a Chicago architect paying tribute to the history of the American skyscraper in the Middle East, or the frivolous mediatic rhetoric of an Indian educated in New York’s Columbia University, who claims to be evoking both the Himalayas and Batman’s city.

Until the new skyscrapers designed for the Persian Gulf and India are finally completed, the top of the world will continue to be Taipei 101, a historicist tower that resembles a vertical pagoda, raised in the capital of Taiwan..

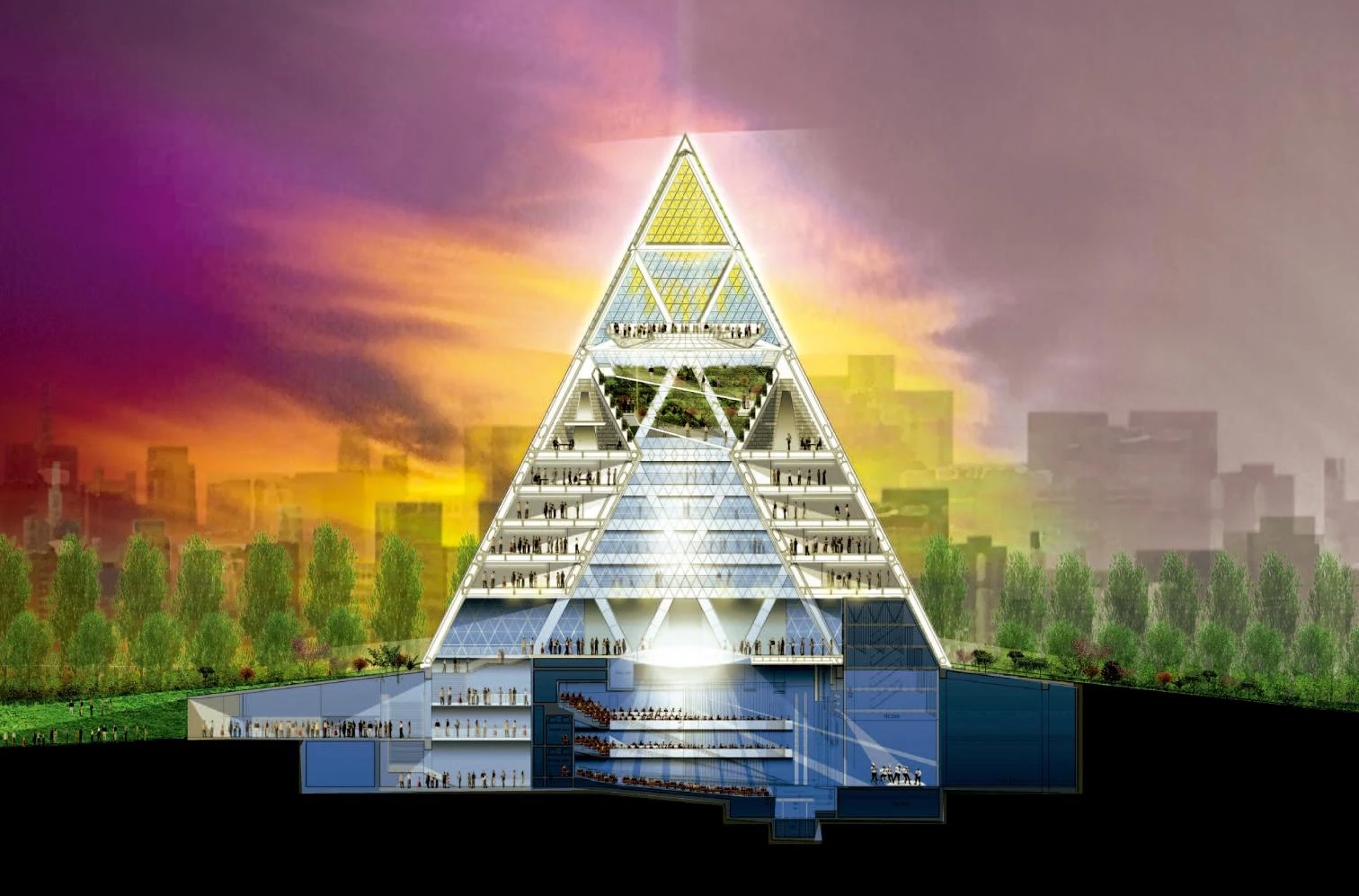

As removed from Mile High Illinois as from Gotham City, but sharing in both the visionary symbolism of Wright’s project and the innocent futurism of Bob Kane’s movie sets, the pyramid designed by Norman Foster for the new capital of Kazakhstan is an extraordinary testimony of the economic dynamism of those ex-Soviet republics endowed with natural resources, and also a rare product of the at once paternalistic and corrupt despotism that is being shaken by the recent tide of popular movements, the contagious fervor of which, after the ‘pink revolution’ of Georgia in 2003 and the ‘orange revolution’ of Ukraine in 2004, has spread to Central Asia in 2005 with the uprisings of Kyrgyzstan in March and Uzbekistan in May. Although the Kazakhstan of Nursultan Nazarbáyev (president since this steppe country of 15 million people and 2,7 million square kilometers became independent in 1991) has yet to be affected by the revolts that have destabilized the two republics delimiting its southern border, where Islamic presence is stronger, efforts have been made to exorcize the risks inherent in its own religious and ethnic diversity, and a case in point is this remarkable project, which presents itself as a symbol of reconciliation and unity under the name ‘Palace of Peace’.

If the Burj Dubai, designed by the Chicago office of SOM, evokes the Mile High Illinois devised by Wright, the Noida tower, drawn up by Hafeez Contractor, interprets the Millennium Tower of Foster through the language of cartoons.

Situated in the center of Astana – the country’s new capital, which Kisho Kurokawa drew up in 1998 with a monumental, symmetrical, and severe plan –, along a ceremonial axis that connects it to the Presidential Palace, Foster’s pyramid is a colossal construction of colored glass, stone, and steel that contains an opera house, a culture museum, a university of civilizations, and a center for ethnic groups, as well as a circular hall at the top (underneath stained glass windows designed by a friend of the architect, the artist Brian Clarke) that is to be the venue for a triennial congress of international religious leaders. Built in a rush by a Turkish firm with the aim of inaugurating it in June 2006, before elections and in time for the second religious congress, the work of Foster and Partners inevitably recalls the utopian projects of the French Enlightenment architects Étienne-Louis Boullée and Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, who used elemental geometric forms like the sphere, the cone and the pyramid to express the authority of reason, and which the British office recognizes as a source of inspiration. It also evokes the visionary proposals of Buckminster Fuller, the American engineer whose domes and geodesic tetrahedrons have had a lasting influence on the career of his follower and friend Norman Foster.

The Peace Pyramid, which is going up in Astana, the new capital of Kazakhstan, is a project by Norman Foster that uses elementary geometry to express the visionary desire of uniting all the religions and ethnias..

The 62 meters of the Kazakhstan pyramid, enhanced by the podium hidden beneath a gentle rise of the terrain, give it a grandiose scale, which the spectacular space of the atrium, extended with an oculus over the opera house to a height exceeding that of Santa Sofía, exalts with its luminous aura: a dimension much surpassing the 21 meters of I.M. Pei’s polemic pyramid in the courtyard of the Louvre, but definitely at a distance from the original 145 meters of the Giza pyramid, though this will not stop people from tagging him with Pharaonic ambitions, just like the political patron of the Parisian iconic construction, François Mitterrand. Nazarbáyev is quite another case, and the rigid ruling of the country that has made it possible to move the capital from Almaty, near the Chinese border, to Astana – a totally new city, like Brasilia or Chandigarh, located at the center of the territory along the trans-Siberian railway line, but at the cost of a more rigorous and extreme climate than in the old capital – does not seem to have been achieved without totalitarian control of dissidence and the mass media. In the steppes of Central Asia, architecture continues to give monumental form to political will, erecting transparent symbols of autistic authority and patrimonial power.