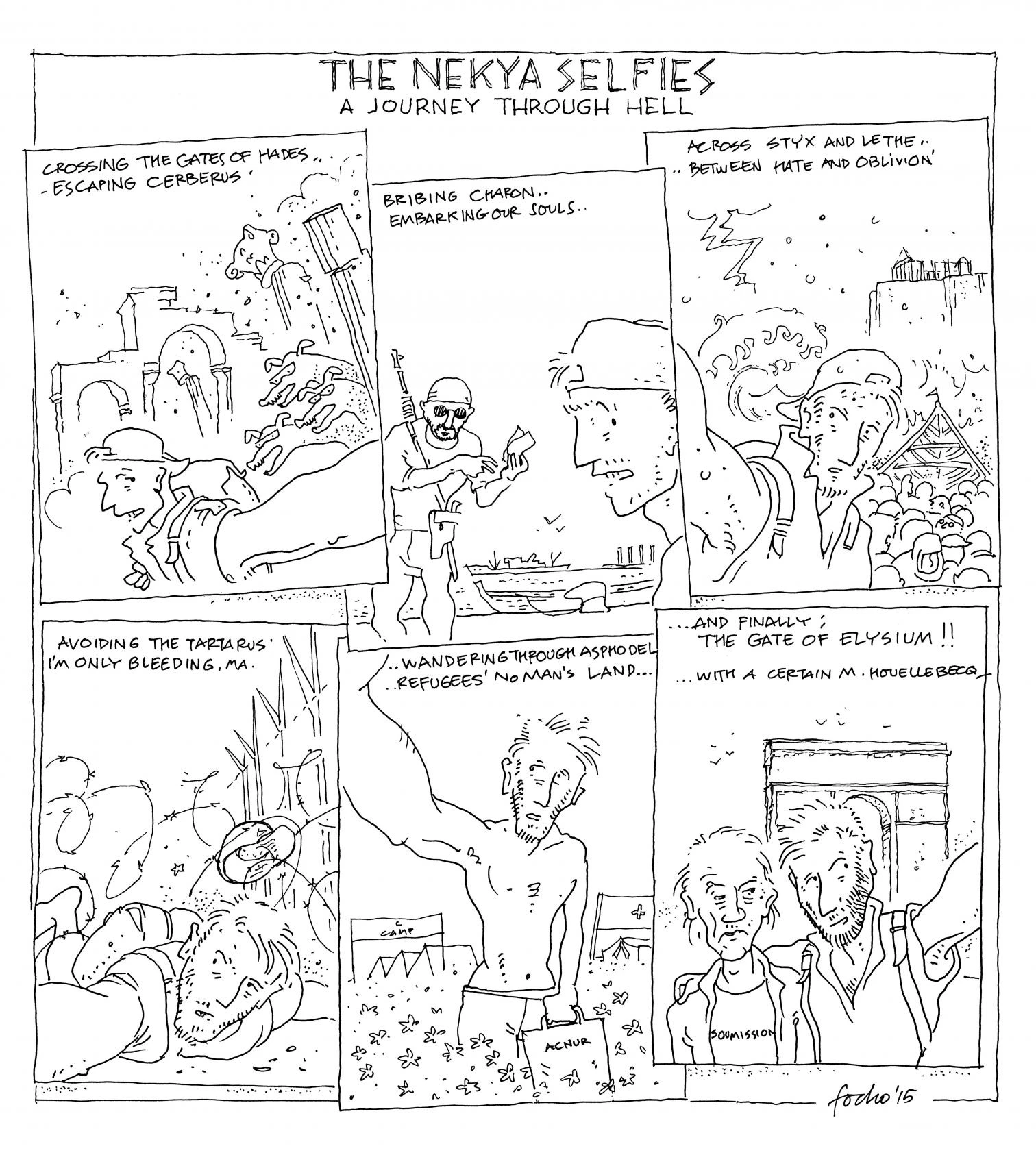

They are not barbarians, and yet we guard against them as though they were. Countries have been mobilizing their armies, erecting fences interwoven with concertina wires, restricting rail traffic, and reinstalling border checkpoints that the Schengen Treaty now seems to have left in the past for good. And all this to put an end to the caravans of people expelled by a theoretically distant war that has blown up monuments, but above all societies: a war which those same countries, in the first place, did not know to stop or prevent, or did not want to.

The utopia of a Europe united only by the euro has proven weak in the face of these migrations, and we cannot tolerate the heat emitted by the zones of friction that the same Europe so expertly built not so long ago: the shielded hot lines of the frontiers. But maybe neither the cordon sanitaire of the euro nor the palisades we keep building in the image of Hadrian’s old way (which seemingly so inspire Donald Trump) can halt the assault. It is not the economy, but geopolitics, that goes back to its old ways to impose its inexorable law.

In the meantime, partitions and ominous quotas are being debated on, and the safety of an entire continent is being entrusted to a thin red line: never before was so much expected of architecture… But there may be another solution, that suggested by a Greek poet, Constantine P. Cavafy, a hundred years ago: “And some of our men just in from the border say / there are no barbarians any longer. / Now what’s going to happen to us without barbarians? / Those people were a kind of solution.”