Temples in Times of Tribulation

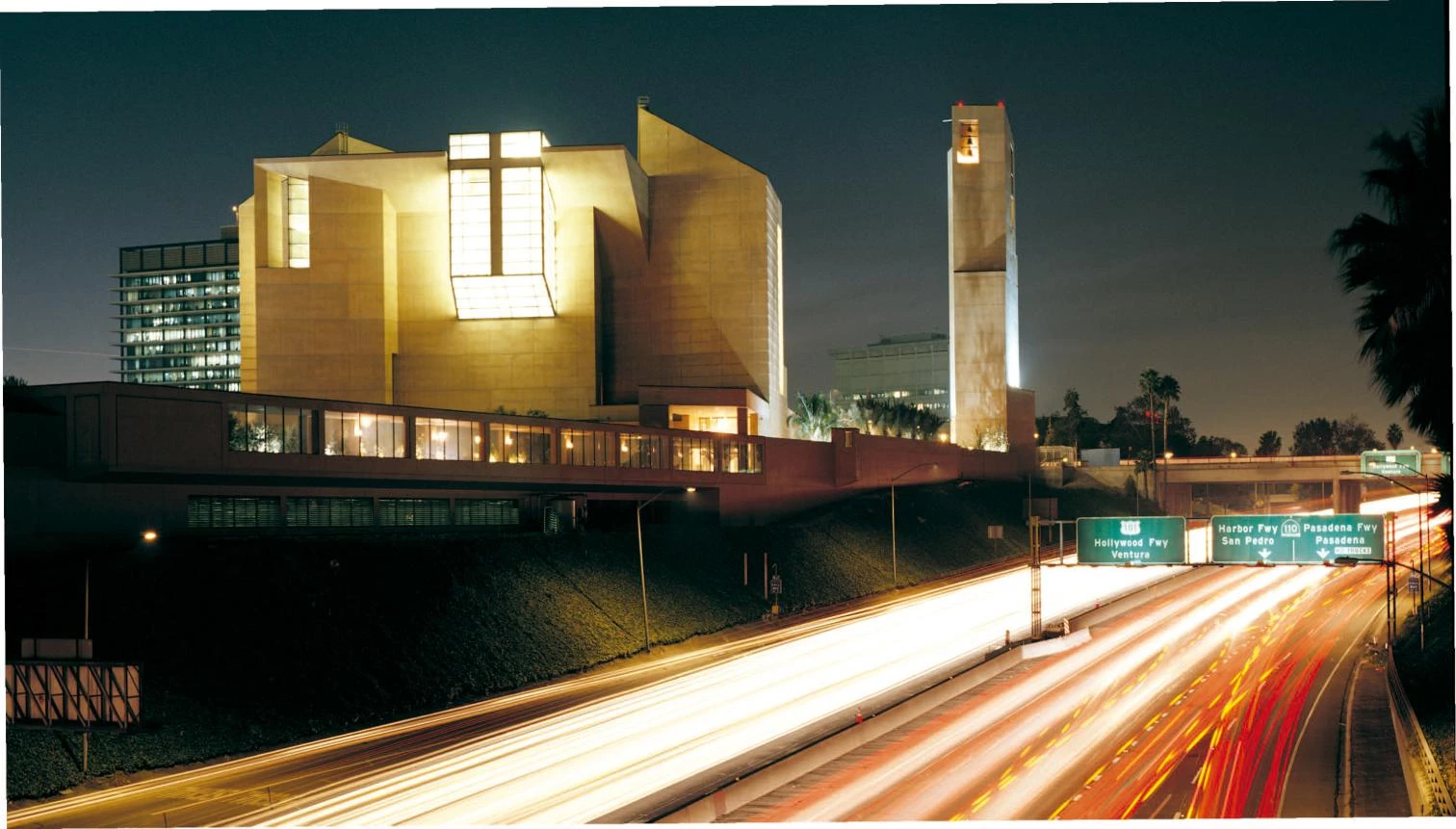

The inauguration of the new Los Angeles cathedral, the largest American work of Rafael Moneo, comes after an annus horribilis for the Catholic church.

You must come to see it.” Under the high frescoes of Rome’s Palazzo Colonna, Frank Gehry demurely resists commenting on the progress of his Disney Hall, the auditorium he is building just three blocks from the cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, the concave and convex stainless steel surfaces of which will be wrapped up in time for the musical season of 2003. He would rather discuss the work of his colleague Rafael Moneo. “It is not so much its exterior, or the gleam of the alabaster windows; what is really beautiful about it are the interior folds of the walls, and the way the light falls on them.” At 73, the Californian architect props himself with a cane, but drops it when describing with his hands the folds of the temple. Six years ago, at a Pritzker ceremony like this one, contemplating Los Angeles from the acropolis of the Getty Center, then under construction, Moneo received both the award and the commission to build the cathedral, chosen by Cardinal Roger Mahony over two local contestants, Thom Mayne and Gehry himself.

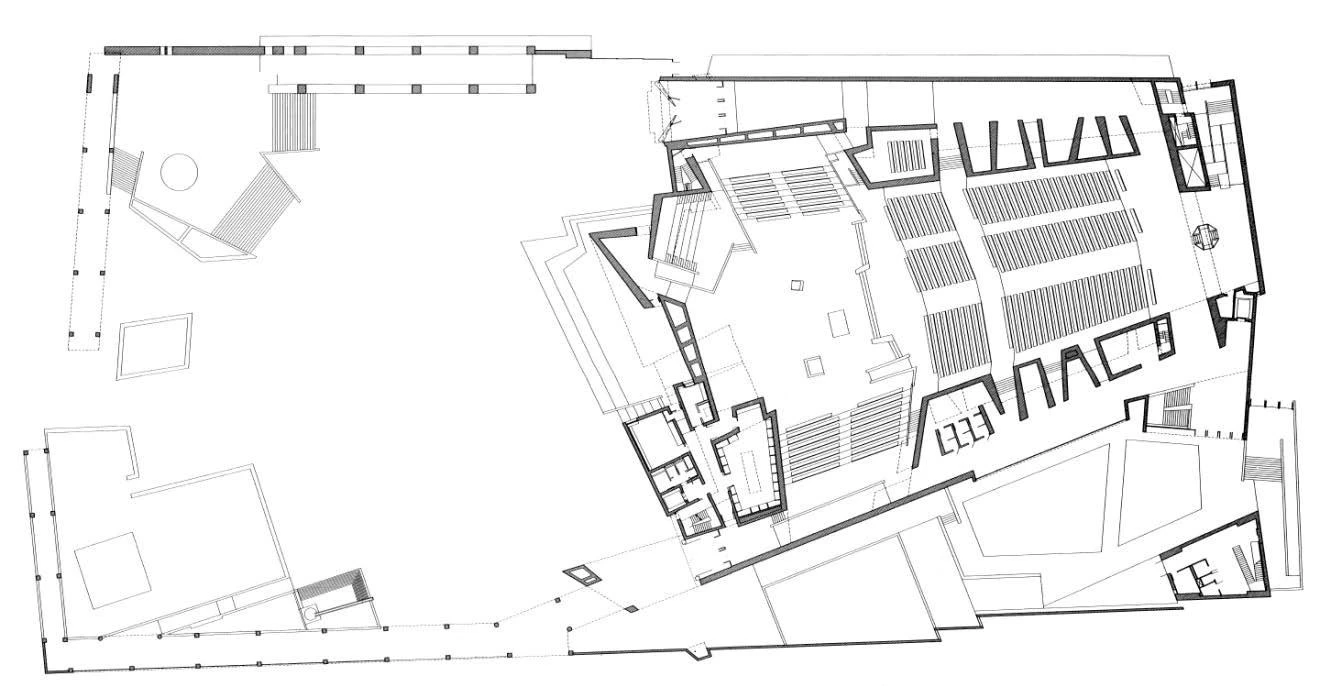

The layout of the temple is indebted to both historic and modern religious architecture.

Moneo’s work, the first Catholic cathedral to go up in the United States in 25 years, will be inaugurated in September not by the Pope (who despite his physical condition will be traveling to Mexico shortly before) but by Mahony himself, whose vigorous leadership of the country’s largest diocese has in the past months been dimmed by the scandal of pedophile clerics that has sparked an unprecedented crisis in the American church, and that in May brought the twelve American cardinals to Rome for an exceptional audience with the pontiff. Mahony soon assumed leadership of the hierarchy’s strictest sector, boasting a policy of prevention (although, as Garry Wills claims in The New York Review, the archdiocese was comitted to it by a judicial settlement with one of the victims) and advocating ‘zero tolerance’ towards pedophilia. Advised by Sitrick, a public relations firm in Hollywood, the cardinal of Los Angeles has proposed police investigation of applicants to seminaries, as well as the immediate reporting of any suspicious behavior.

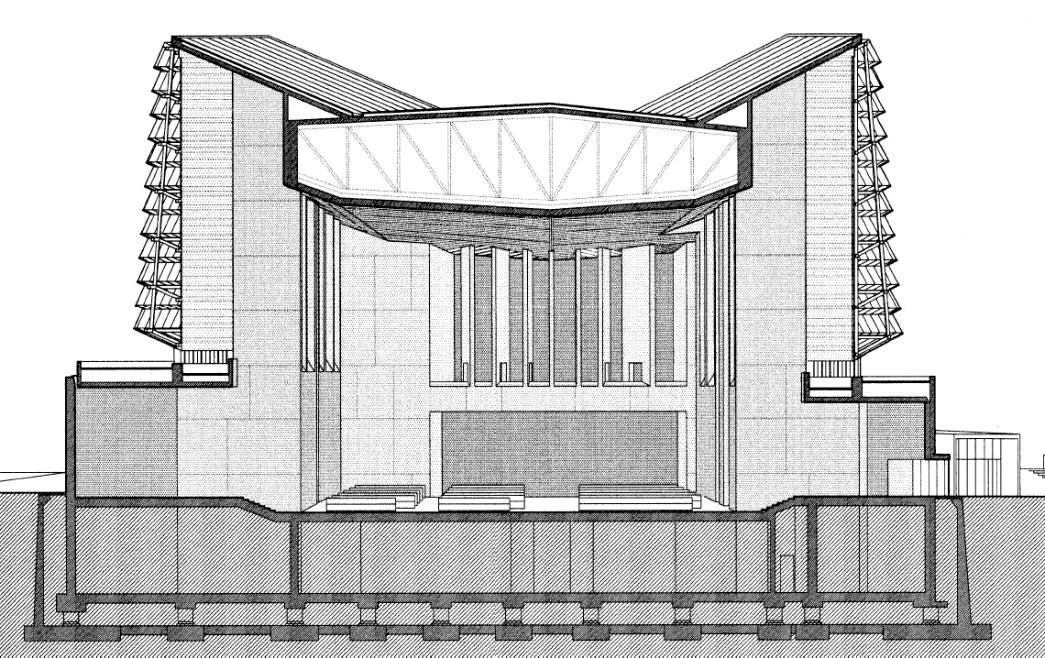

The folds on ceilings and walls multiply the effects of light, traditionally used to evoke the experience of the sacred. Cut out against a window of glass and alabaster, the large cross presides both the altar and the exterior ceremonies.

In such an atmosphere of devastating tension, of confidence crisis of the faithful towards pastors, and of millionaire indemnizations to victims, Moneo’s cathedral will inevitably be associated with his client Mahony; the fractured forms of the building, which at another time would have provoked deconstructivist or seismic metaphors, will be judged as an expression of the uncertainty that afflicts the church; and its colossal opalescent interior of concrete and alabaster will be taken, beyond the con-ventional theological association with divine light,as a dazzling and muscular manifestation of a thou-sand-year-old institution’s confidence in the future. “There will not be a building like this in the whole country; a splendor that takes your breath away,” Mahony has said – vigorous words that encapsulate the brisk and populist spirit of a powerful man of the church who has exchanged the hermetic subtleties of the Vatican’s Curia for the pragmatic visibility of American mediatic spectacle, for which a judicial demand and a work of architecture are essentially questions of image.

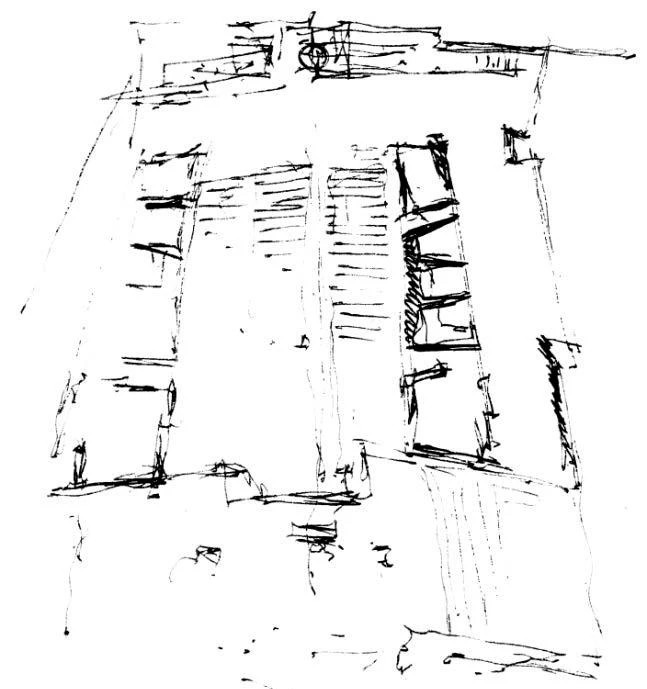

Although any building ends up symbolically sequestered by its circumstances, it would of course be absurd to interpret the Los Angeles cathedral in terms of the present situation, attributing to the architect a capacity to forecast ecclesiastical storms. Nevertheless, it is evident that its complex orchestration of innumerable fragmentary episodes, its in-tricate geometries, and its typological indecision admirably illustrate the conflictive nature of the times. Moneo himself, who normally supplies his critics with the most elegant metaphors and the most pertinent references, in this case could not resist offering a deluge of sources and intentions: the pedestrian premise along the freeway, formed as a plaza with buildings and arcades, would be inspired by the Franciscan missions of Friar Juniper; the folded concrete walls and alabaster screens would come from the Miró Foundation; the sculptural definition of the volume and the inclined section of the nave would be a titanic echo of Le Corbusier’s chapel in Ronchamp; the visual contact between the interior of the church and the cloister would have its origin in the side aisle that opens on to the landscape in Bryggman’s Turku chapel; and the aerial cross that will preside over both the religious ceremonies held on the esplanade and those celebrated inside the temple would take its solitary and hypnotic monu-mentality from Asplund’s crematorium. But the cathedral would also be Romanesque in its solid and somber severity, Gothic in its challenging and emphatic verticality, Byzantine in its diffuse lantern-like luminosity, Baroque in the magic of its transparente in the apse...

The raised position of the plot led to the design of a platform overlooking the highway which supports the temple and its different auxiliary spaces, shaping a public plaza that gives a civic dimension to the religious monument.

Could we add anything else to this palimpsest of references? Yes. We could also point out the mark of Alvar Aalto’s civic centers in the organic still life of pieces on a tray, Moneo’s debt to Utzon in the urban conception of the platform, Siza’s influence in the topographic interpretation, Gehry’s print in the volumetric fractures, or a tribute to Scharoun in the design of the assembly area – an expressionist wink at the Philharmonie that is explicit in thesketches, and that significantly shares with its neighbor, the Disney Hall. And we could equally note the amalgamation of features present in previous projects of Moneo, whether the tower and saw-like glass walls of Madrid’s Atocha Station, the urban implantation and double facades of the Kursaal in San Sebastian, the picturesque exfoliation of mass and the domestication of scale in the Barcelona Illa, the rhythmically perforated facade and palpitating pavements of Murcia’s Town Hall, or the ornamental bands and spikes that emerge at each step in a work at once fascinated by and ge-netically incompatible with abstraction. In the end, nothing is as important as the absence of cohesion between the parts, which present themselves to us as if they were voluntarily unbounded, with the moving vulnerability of a skeptical century.

The inverted chapels – the most significant typological innovation of the project – open to a side aisle (left), that defines a processional itinerary leading the faithful from the plaza entrance to the nave.

The cathedral feigns integrity in the homogeneous concrete and in the sedative gleam of the interior light, but such unitary fiction perishes in the conflict between the ritual Latin cross floor plan and the theatrical demand for an enveloping place. The result of this violent hybridization is a unique space, of an archaic gravitas in the expressive trace of its footprint, and of a cinematographic spectacularity in the luminous height of the nave, which one enters through the mannerist and magical processional itinerary of the walkway of inverted chapels that is the project’s major typological innovation, and which culminates in the cross of concrete that floats above like a delicate bird of rice paper – an epiphanic episode of alabastrine light that sums up the work and justifies Mahony’s emphatic phrase: “a splendor that takes your breath away.”

Meanwhile, eight time zones away and 120 years after its construction began, the Expiatory Temple of the Sagrada Familia continues to rise on the basis of the uncertain information left by its architect when he died, over three-fourths of a century ago. The Gaudilatry unleashed by the onset of his 150th year has not helped put a stop to an artistic sacrilege being waged against a piece of sacred architecture that is both erotic and edible. The Church is hence a sinner violating its heritage, before the passivity of the same courts of justice that demand the demolition of Grassi’s Theater of Sagunto, are unable to impose urbanistic discipline on Madrid’s parishes, or lose their way in the labyrinths of ecclesiatical investments in fiscal havens and corrupt financial companies. The Spanish bishops, who do not easily accept the term immoral for their ethic ambiguity towards ethnic criminality, should perhaps refrain from playing on the political arena, and examine instead their own consciences, hopefully recalling both the Fifth Commandment of Mosaic Law and the universal vocation of Paul’s Church. We demand from Islamic theocracies an enlightened and lay revolution that separates the temporal from the spiritual, but the illusion of the City of God remains present in the third Christian millennium. In these strange and trying times, there seems to be more spirituality in architects than in clerics.