Porcelain Seeds

The colossal installation by Ai Weiwei at the Tate is a masterly portrait of contemporary China that combines artistic excellence and political intention.

Ai weiwei has carpeted the Tate Modern in London with 100 million sunflower seeds. Made of porcelain and painted individually by an army of 1,600 craftsmen, the delicate ceramic seeds cover the floor of the huge Turbine Hall with a thick layer that crunches with each step, forming an interior landscape that is both a poetic manifesto and a political statement. The Chinese artist, architect and activist who with the Swiss partners Herzog & de Meuron designed the ‘bird’s nest’ for the Olympic Games of Beijing in 2008, has with this work produced a rare amalgam of aesthetic excellence and civic commitment. The contrasts of contemporary China, but also the dilemmas of our world, are encapsulated in this vast expanse of identical but different seeds.

The 100 million sunflower seeds were handcrafted in porcelain with traditional techniques, and painted one by one to compose a symbolic landscape that defends the uniqueness of the individual in the mass society of our time.

The uniqueness of these tiny objects, which in spite of their unimaginable number are not mechanically reproduced, refers of course to the conflict between individual and mass that, while manifesting itself dramatically in China, is not alien to our own industrial and urban societies. In the final analysis, the irritation of Chinese leaders at the Nobel going to Liu Xiaobo must be under-stood as disconcertment with the tribute to a tiny sunflower pip that puts human rights ahead of the material well-being of millions of people, in the unanimous framework of the consumerism-Leninism that expresses and legitimizes the re-gime: a state capitalism that also thrives in other latitudes, from Russia to the Gulf, and which is enjoying an unexpected bout of popularity thanks to the financial crisis of 2008.

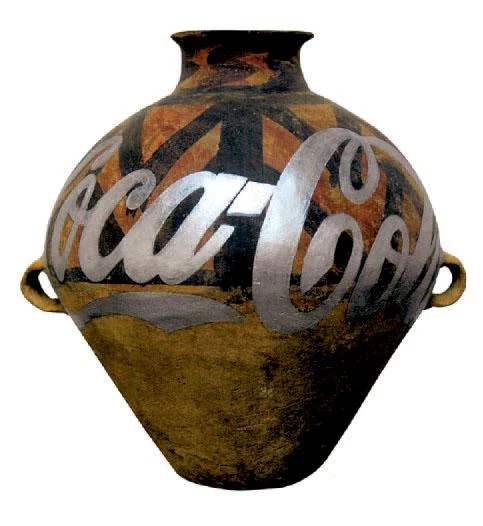

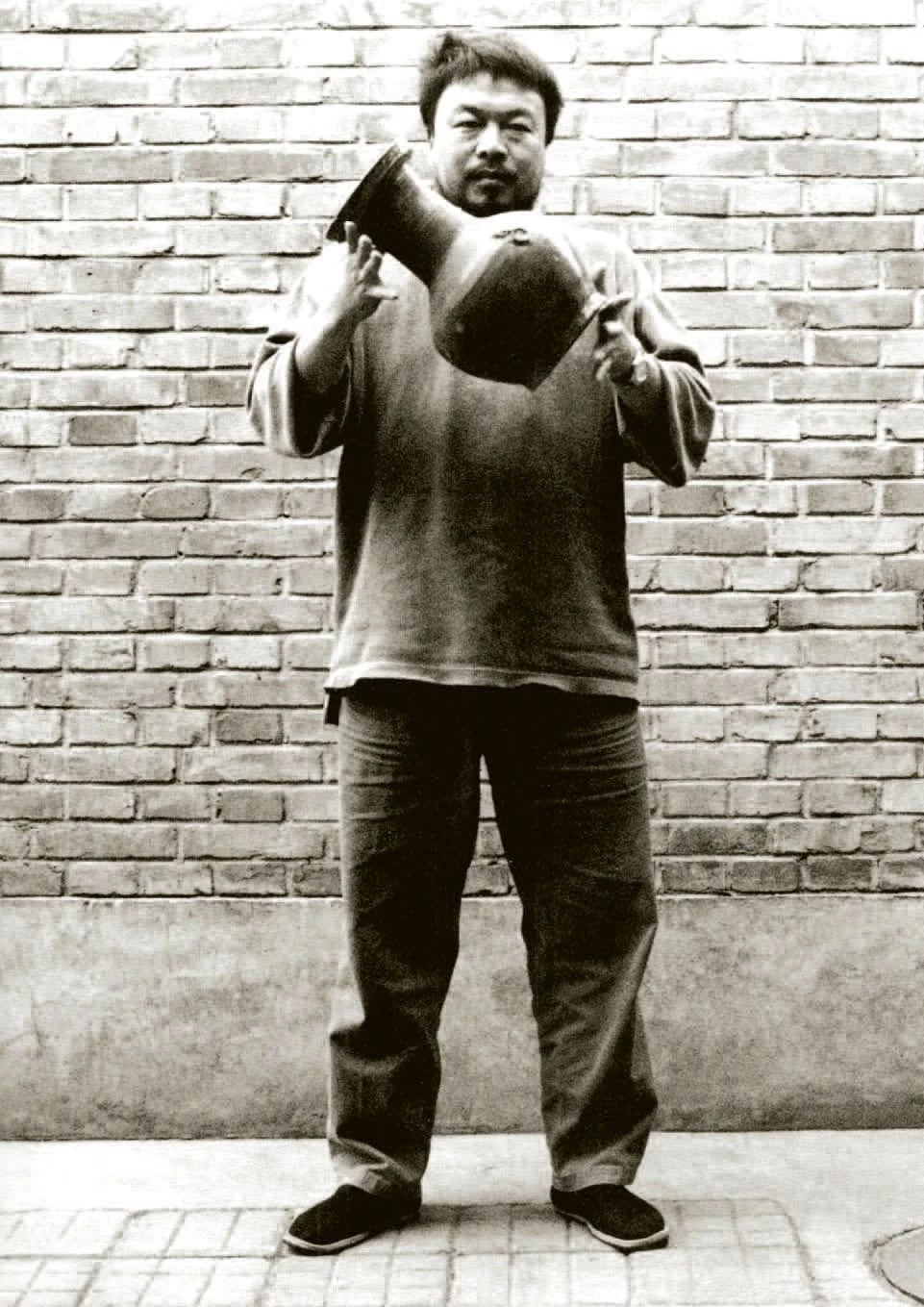

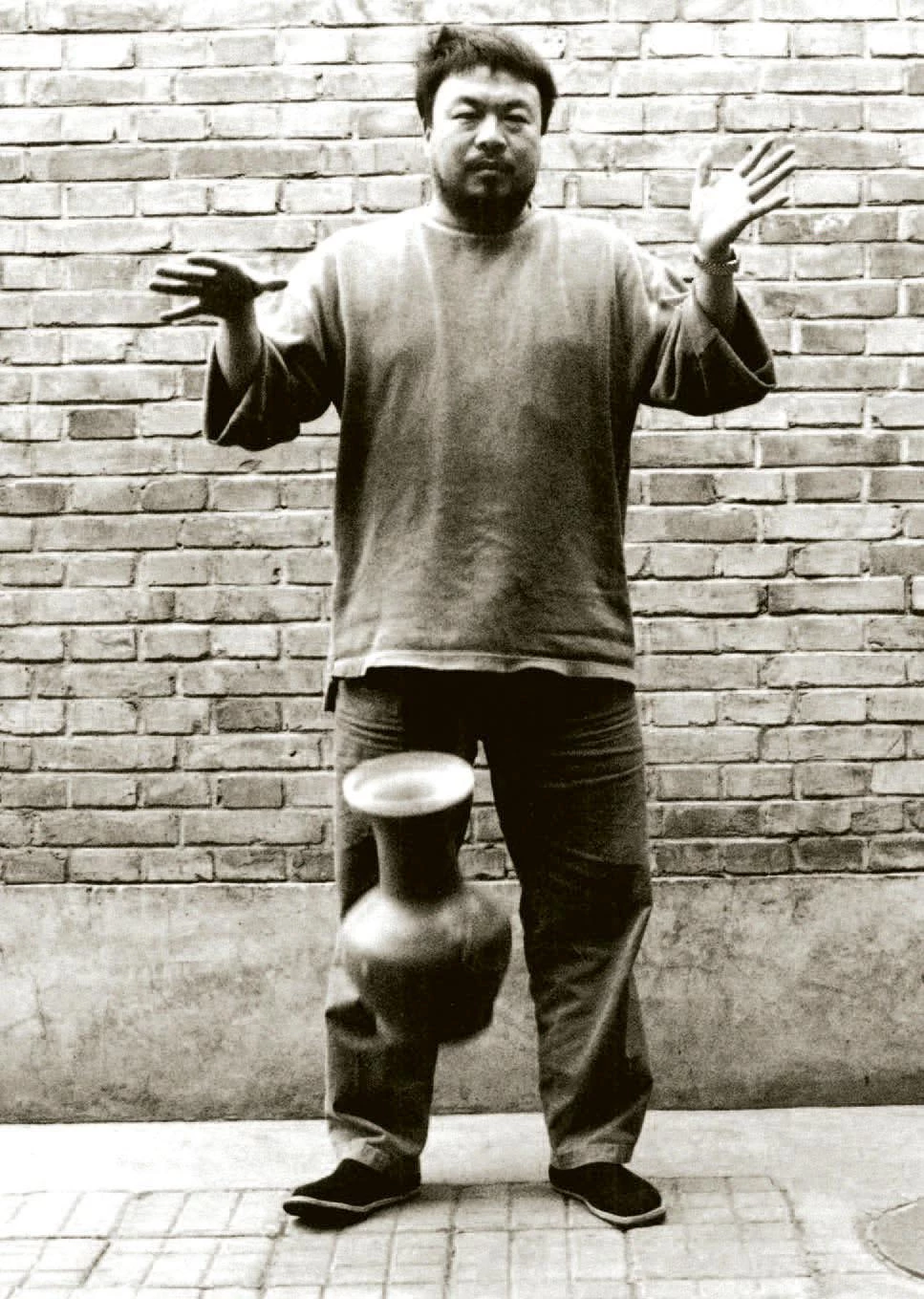

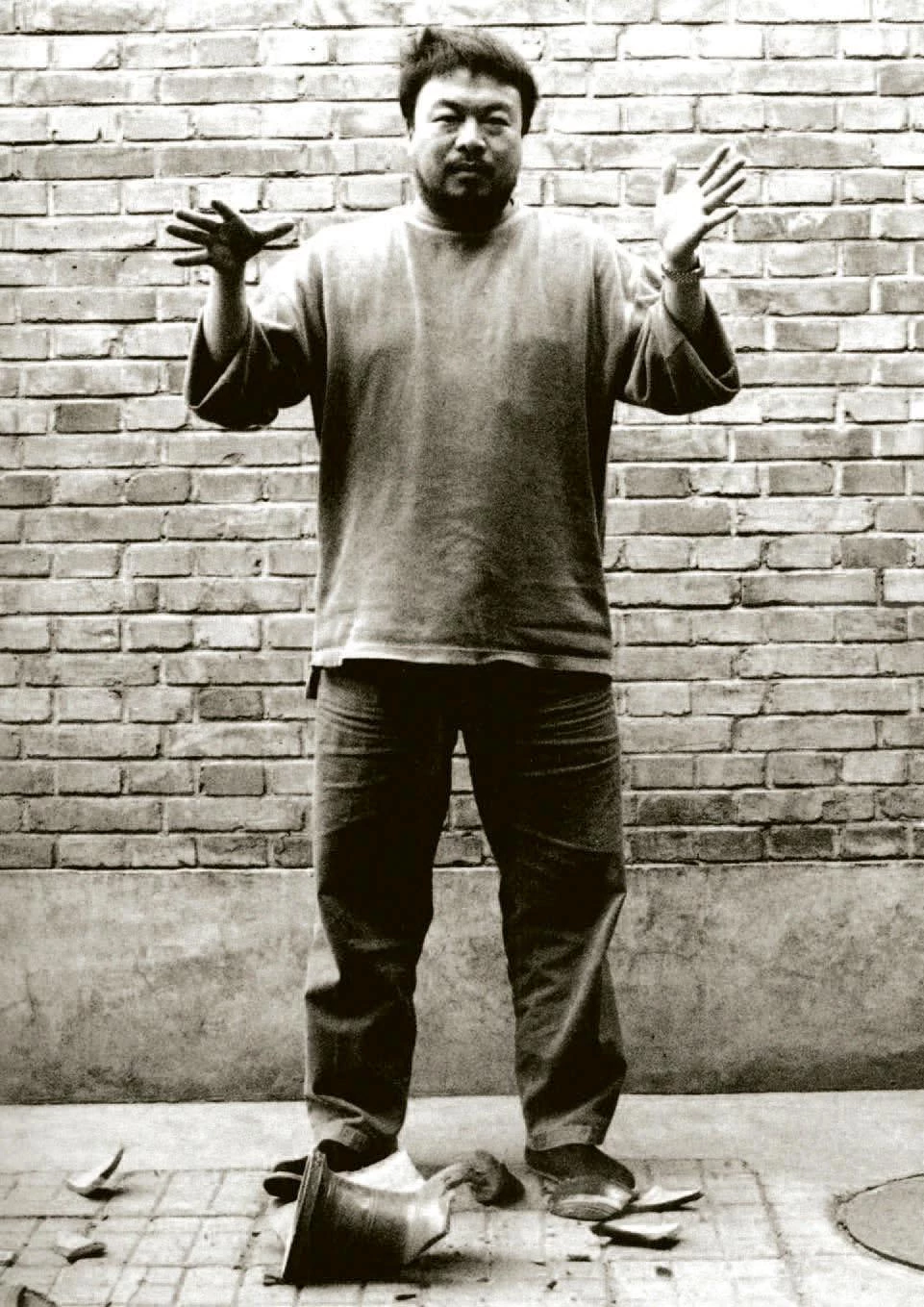

Traditional Chinese ceramic – and porcelain, which is a symbol of the country – has been used by Ai Weiwei in his work, either to disfigure it with commercial logos or to destroy it as signal of a break with the past.

We are still immersed in the shadow of the col-lapse of Lehman on a September 15, and it may be true, as some analysts of the English-speaking world suggest, that this date changed the world more than the ominous September 11 did, because whereas it is hard to think of the emergence of a global Muslim caliphate as the geopolitical back-drop of 9-11, we do not have to stretch our im-agination to acknowledge 9-15 as a turning point marking the shift from United States hegemony to a multipolar planet where Asia comes to the fore as the continent of the 21st century and China is already the second economic power. The state with the most foreign exchange reserves and the largest volume of exports is also the most ambitious buyer of energy and raw materials companies in Africa and Latin America, former backyards of Europeans and North Americans, and this economic boom feeds the self-esteem of a ‘Middle Kingdom’ that has never felt culturally inferior to the West.

Shortly after China’s sorpasso of Japan in August 2010, when the figures for the year’s second quarter were made public, and in lectures held at the universities of Tongji and Tsinghua, the institutions in Shanghai and Beijing where the country’s elites are educated, I heard young people of both cities speak in identical terms: “we are the students of the second power, and in fifteen years we shall be the leaders of the first”. Faced with such confidence, one cannot help making comparisons with our own youth, compelled as these are by the crisis to choose between stagnation at home and a wave of emigra-tion that is draining Spain of its finest youngsters professionals and wasting the resources used in their training. We do not seem to be in a position to be giving macroeconomic lessons to China, and neither, I fear, can we claim our political elites, however democratic, to be better than theirs.

With its overwhelming multiplication of ele-ments, Ai Weiwei’s installation evokes China’s demographic power. But it avoids nationalistic exaltation in choosing for a symbol those humble sunflower pips, which used to be shared in a gesture of human compassion and friendship “during a time of extreme poverty, repression and uncertainty”. Son of the poet Ai Qing, the artist spent his child-hood and early youth in the remote labor camp to which his father was deported during the Cultural Revolution, and he himself migrated to the United States as soon as he had the chance to, returning to China in 1993 after over a decade in New York. This life experience is present in an at once radically Chinese and profoundly critical work where a ma-terial as precious and characteristic of the country as porcelain combines with a caustic reference to the omnipresent portraits of Mao surrounded by sunflowers turned toward his dazzling light.

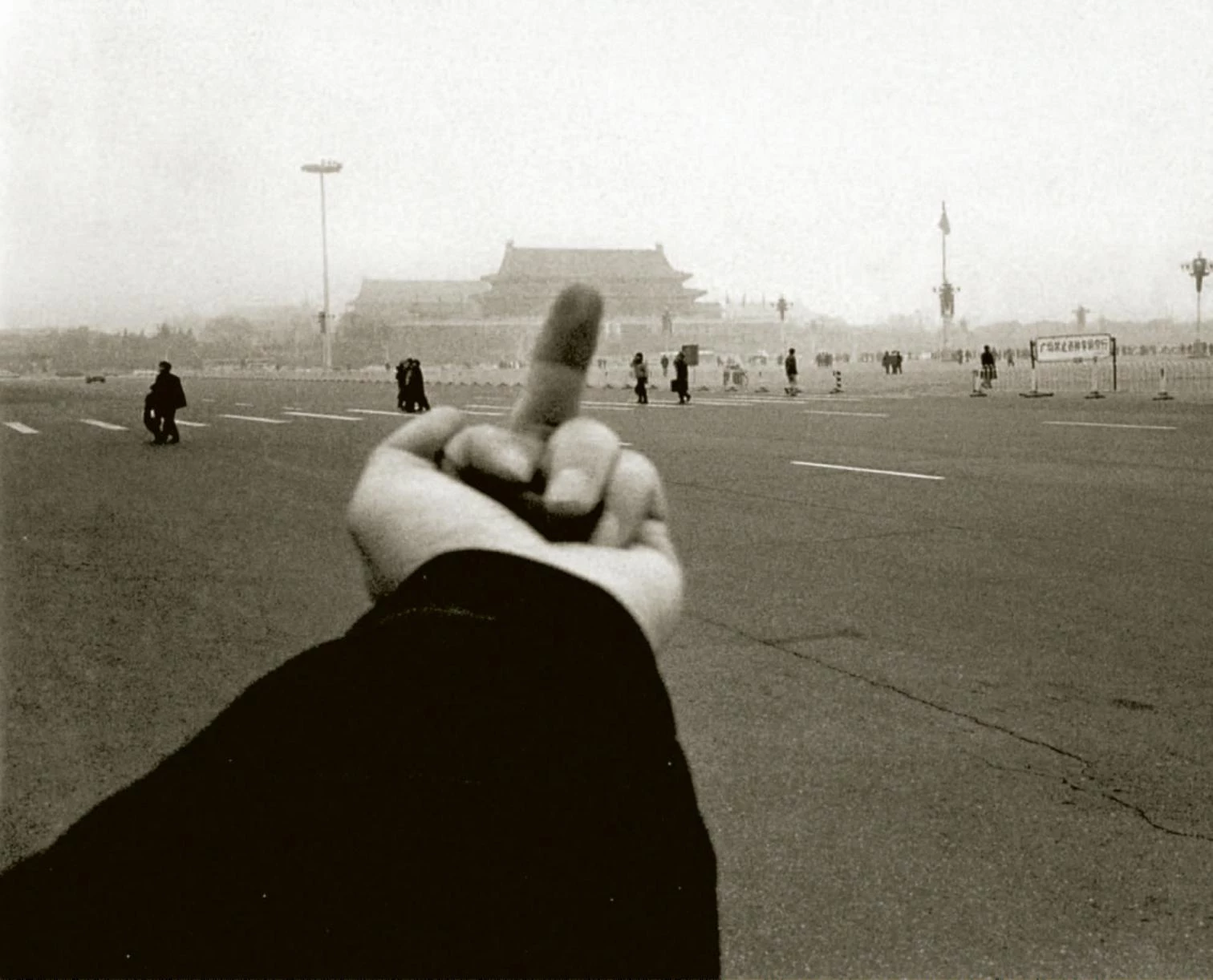

The relationship of the artist with his country is ambiguous, because while being deeply tied to his origins, he does not hesitate to critically represent its links with the past or its current political organization.

If the repetition of everyday objects can be understood in a pop context, here the number is so large as to bring the work close to the romantic aesthetic of the sublime, no matter how much the sheer logistical effort of carrying it out calls for the pragmatic skill of an architect of huge constructions, such as the new airport designed by Norman Foster in Beijing, the planet’s largest building, which Ai Weiwei painstakinly documented by photographing it weekly for three years. The ceramic seeds gathered at the Tate, like any object made of that exquisite material, require a process involving thirty different operations, from extracting the kaolinite to the final baking – the painting alone needs between three and five strokes per side, depending on the skill of the craftsman –, and one can imagine the challenge, apart from the economic boost, that the project must have meant for Jingdezhen, an ancient city that still lives off this languishing art or industry.

A hundred million is of course a figure that is hard to imagine, and yet Ai Weiwei points out that it is not even a fourth of Chinese users of the Inter-net, whom the artist addresses through a cultural and political blog with a huge following – for now only in Mandarin, although visitors to the Tate can record for him videos in English – that has caused him various problems with the government, from censorship of his reports on the deficient school buildings that killed thousands of children in the earthquake of Sichuan to the physical attacks on his person and the video surveillance of his house and studio. But the web and the new media are a territory where artistic and political dialog take place nowadays, and just as Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao invite people to send them e-mails and hold chats online, Ai Weiwei installs in the Danish pavilion of the Shanghai Expo a camera exactly like the one surveilling his house, to send back to Copenhagen images of the provisionally absent Mermaid and its visitors, who from time to time take advantage of the open connection with the West to send dissident messages.

Artisan and massive, the installation at the Tate also plays with the ambiguity of falsehood, which for so many reasons we associate with the oceanic Chinese commerce of replicas and imita-tions, although there is an inversion here because what looks like a small sunflower pip is actually an exquisite object of fine porcelain. The reality of the country is exactly the opposite, inundated as it is with cheap illegal reproductions of western products, in a dynamic and prosperous market that situates itself outside the bounds of intellectual property and does not exclude architecture magazines like this one, translated to Chinese and sold in university campus street stands for much less than its selling price in Spain. Here, too, they win, and this fascinating and contradictory reality is also referred to by Ai Weiwei’s hundred million fake sunflower seeds, which can no longer be stepped on after warnings of health officials that the dust emitted can be harmful to visitors. Big Brother watches over us, see the exhibition on the web.