“Why have there been no great women architects?” It seems a good time to rephrase the question with which in 1971 the American historian Linda Nochlin began one of the seminal texts of gender studies and feminist art criticism. The absence is just as present in architectural historiography, and although the omission is being corrected and our modern heroines are being given their rightful places, many stories have yet to be rescued from oblivion.

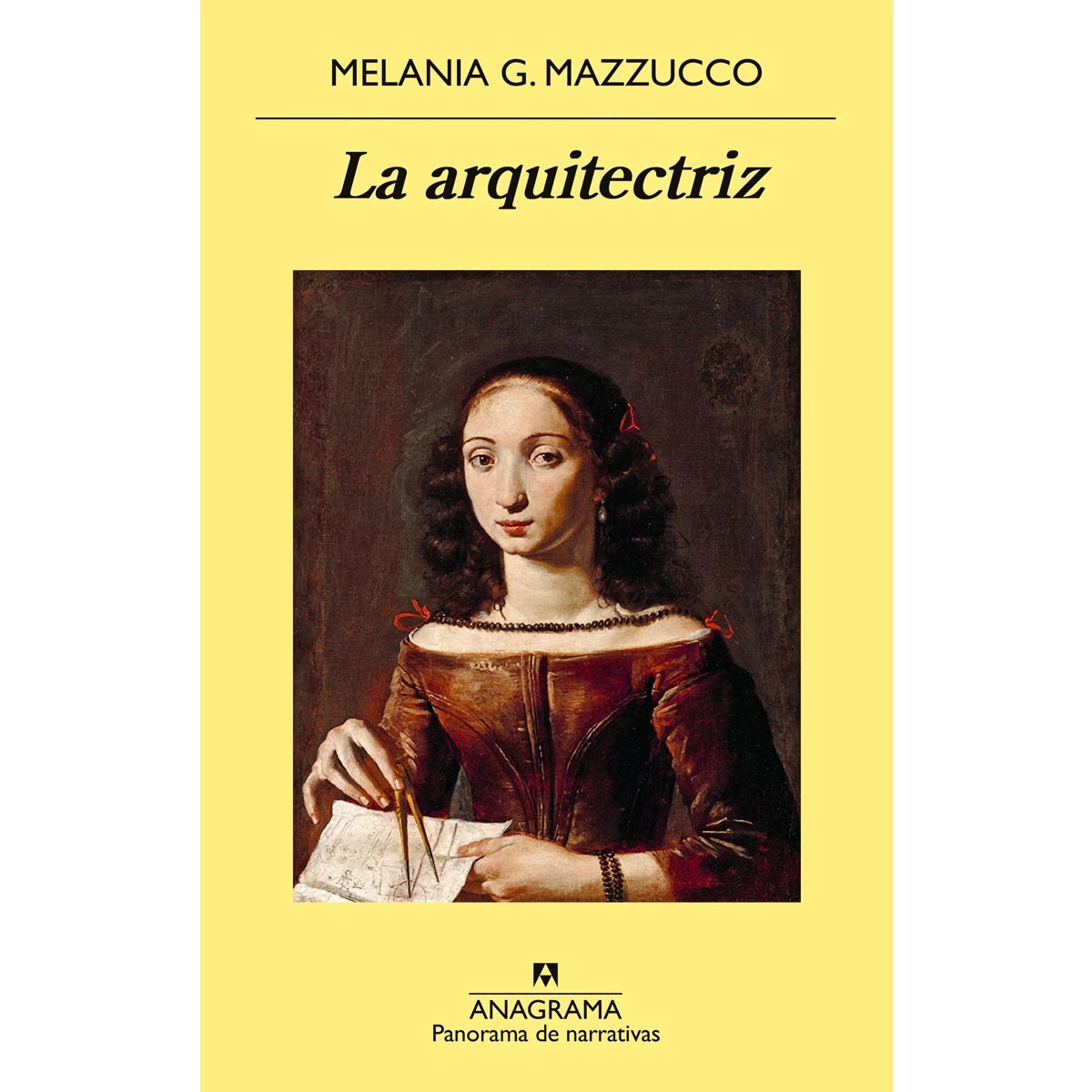

This is the starting point of the novel by Melania Mazzuco, who in her usual work of saving people ignored by official histories painstakingly reconstructs Baroque Rome, but through a narrative that deviates from hegemonic canons and in which known lead actors become secondary. So Popes Urban VII and Innocent X, the likes of Guido Reni and Pietro da Cortona, and rivals like Bernini and Borromini are just background characters in the life of a young woman who aspired to be a symbol of change, of a new age, and of a fresh start for all women.

The story of Plautilla Bricci – the world’s first female architect or architettrice, as she called herself – is that of many other women who were recognized by their contemporaries but saw their works relegated or attributed to some male. But now we know that the author of Villa Benedetti also built a chapel in San Luigi dei Francesi, or the Palazzo Testa-Piccolomini. This other way of writing history may help to pull strings and redeem disregarded biographies. As the artist Jo Spence illustrated, the best way to not be erased is by being written.