Paolo Veronese, The Feast in the House of Simon, h.1556-1560

There is no better architecture exhibition this summer than that of Veronese at the Prado. The great painter created the myth of rich and opulent Venice with his crowded compositions of exquisitely dressed characters participating in lavish dinners in architectural contexts of stately grandeur, and he did so when the Serenissima was facing economic decline, loss of political power, and religious conflict, suffering heretical uprisings, a setback in the Mediterrranean against the Ottomans, and a tragic plague that killed a third of its population. It is tempting to think that perhaps the iconic buildings with which cities today assert their identity are but scenographies that hide the crisis of societies threatened by demographic decline, geopolitical convulsions, and epidemiological or climatic risks. In this context, the survival of the fragile canvases and pigments with which the artist built the idealized image of Venice is comforting, because we might also be able to deposit a legacy of memory with the fragile means provided by the tempests of history.

Paolo Caliari, known as ‘Il Veronese,’ drew from his lineage of stonemasons a proximity to architecture that earned him the protection of Michele Sanmicheli, the friendship of Jacopo Sansovino, and the admiration of Andrea Palladio that led to the frescoes of Villa Maser, built for Marcantonio Barbaro and his brother Daniele, Vitruvius’s translator. The Dieci libri by the Roman and the Quattro libri by Palladio inspired the painter as much as the buildings, and in what is the most important loan in the exhibition, The Feast in the House of Simon, the biblical scene is framed in a loggia similar to that of Palladio’s Chiericati Palace in Vicenza. Miguel Falomir has placed it between two works that show the different use of perspective in Veronese, whose Christ Preaching in the Temple has a low vanishing point, following the Palladian rule and giving the figures a sculptural monumentality, while Tintoretto raises it in The Washing of the Feet as Serlio’s scenes suggest, scattering the characters and evoking the effect of a sloping stage in a theater.

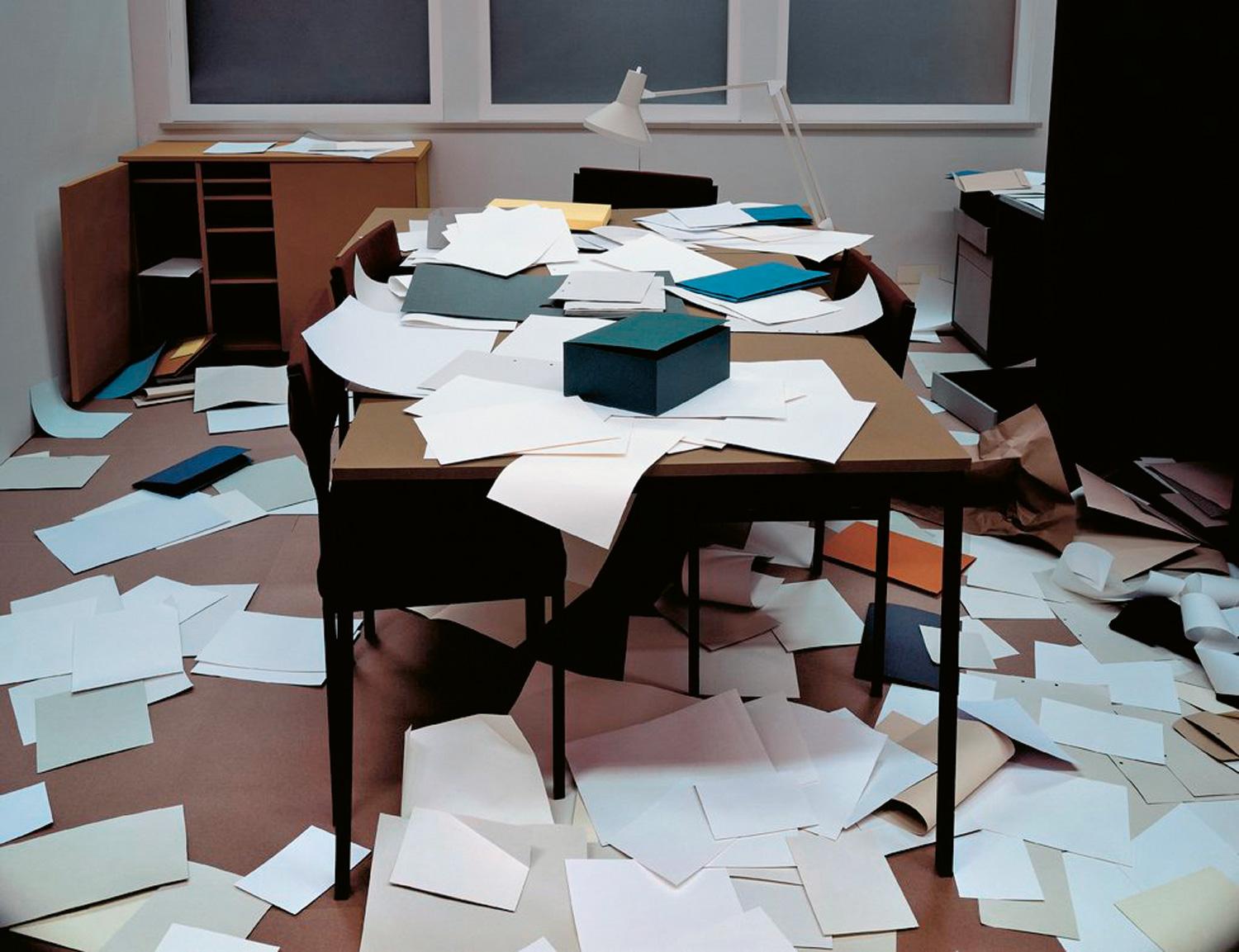

Without Titian’s depth or Tintoretto’s audacity, Veronese belongs to the holy trinity of Venice because of his technical skill, his training as a draftsman to overcome the opposition between disegno and colore, and his mastery in the depiction of atmospheres where luminous, iridescent color suggests shadows without using chiaroscuro. Painter of painters, admired by Rubens or Velázquez, by Delacroix or Cézanne, Veronese is also a painter of architects, and it is hard to leave the museum without thinking about the magical permanence of fabrics containing architectural worlds. Perhaps today no works are as fragile as the paper constructions of Thomas Demand, which the artist photographs to lend them an uncertain survival, and his Büro resonates with the drawing on the last page which celebrates our 40th anniversary. As in the ravaged Stasi office that inspired Demand, the gales of time will raze lives, words, and images to leave only shadows on the floor, and with luck some echoes in the dark of the night.

Thomas Demand, Büro, 1995