Signs of Strength

Inaugurated in New York’s Babel, the year came to a close in Iraq’s Babylon, where the force of the West is breeding the diffuse terror of an uncertain century.

Puttingthe reason of strength before the strength of reason, the only superpower of the 21st century uses the trauma of 9-11 to impose a new imperial order on the planet. Despite the reluctance of allies, the US went into Iraq with the purpose of altering the geopolitical balance in a world where the access to energy is still the essential factor, and where Islamic terrorism is beginning to look like the most threatening element; but military success has neither made the planet safer, nor has it consolidated the economic leadership of the US, that – in view of the disagreements within the EU, the stagnation of Japan, the decline of Russia or the uncertainties of India or Brazil – sees the development of China as the main risk for its future hegemony. From the reconstruction of New York’s Ground Zero to the projects for the Beijing of the 2008 Olympic Games, an architecture of gestures and symbols reflects the emotional temperature of a time more attentive to screams than to whispers.

The Winter Crisis

Manhattan was stage, during the winter, for two simultaneous struggles: in the United Nations headquarters, Washington tried to persuade the Security Council of the need to attack Iraq in search of elusive ‘weapons of mass destruction’; and in the site of the Twin Towers, the architects strove to present their proposals for a reconstruction that would restore the urban fabric and remember the victims. The first conflict was settled with the failure of the multilateral strategy and the decision of the US to launch an attack with the military support of the United Kingdom and the rhetorical backing of Spain, faced with the popular rejection which took shape on February 15 in the largest demonstration in history; the second, with the victory of Daniel Libeskind, who remembered his being an immigrant Jew to defend with jingoism a fractured and elegiac project, rounded off by a tower that evokes the Statue of Liberty and rises to a symbolic height of 1,776 feet.

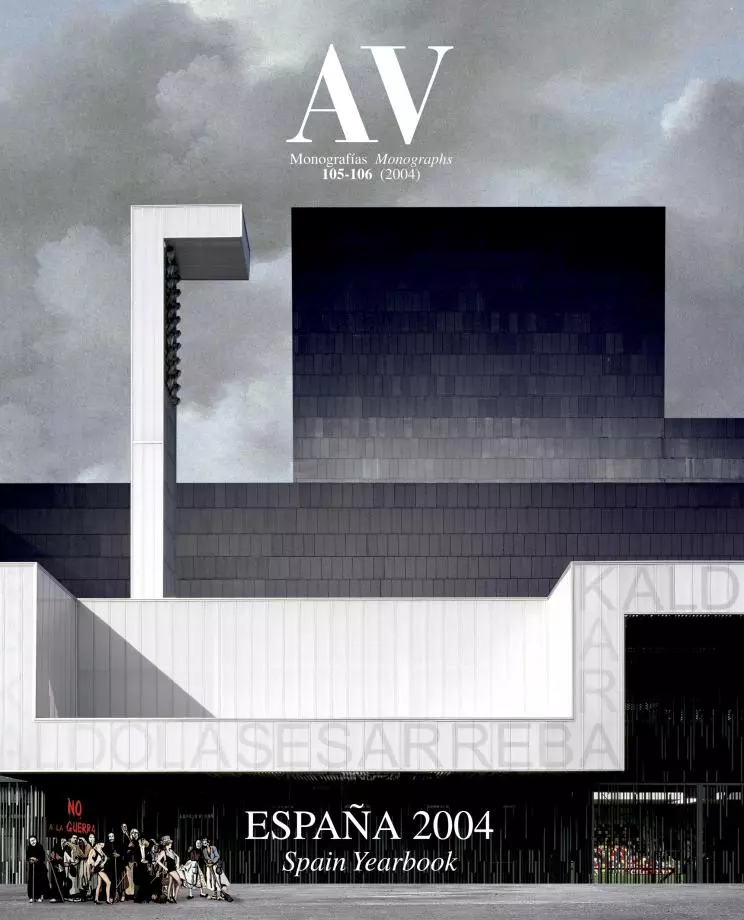

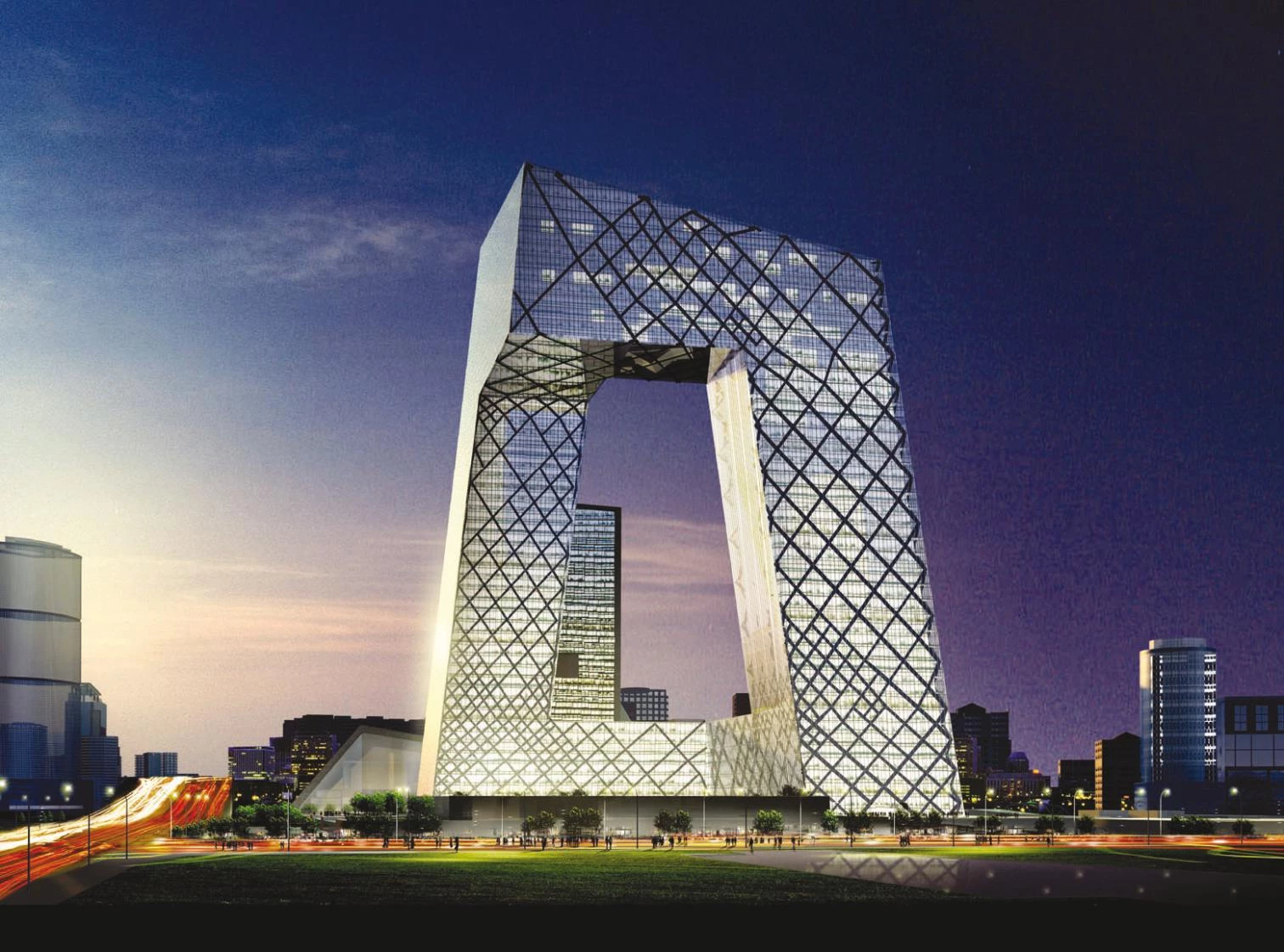

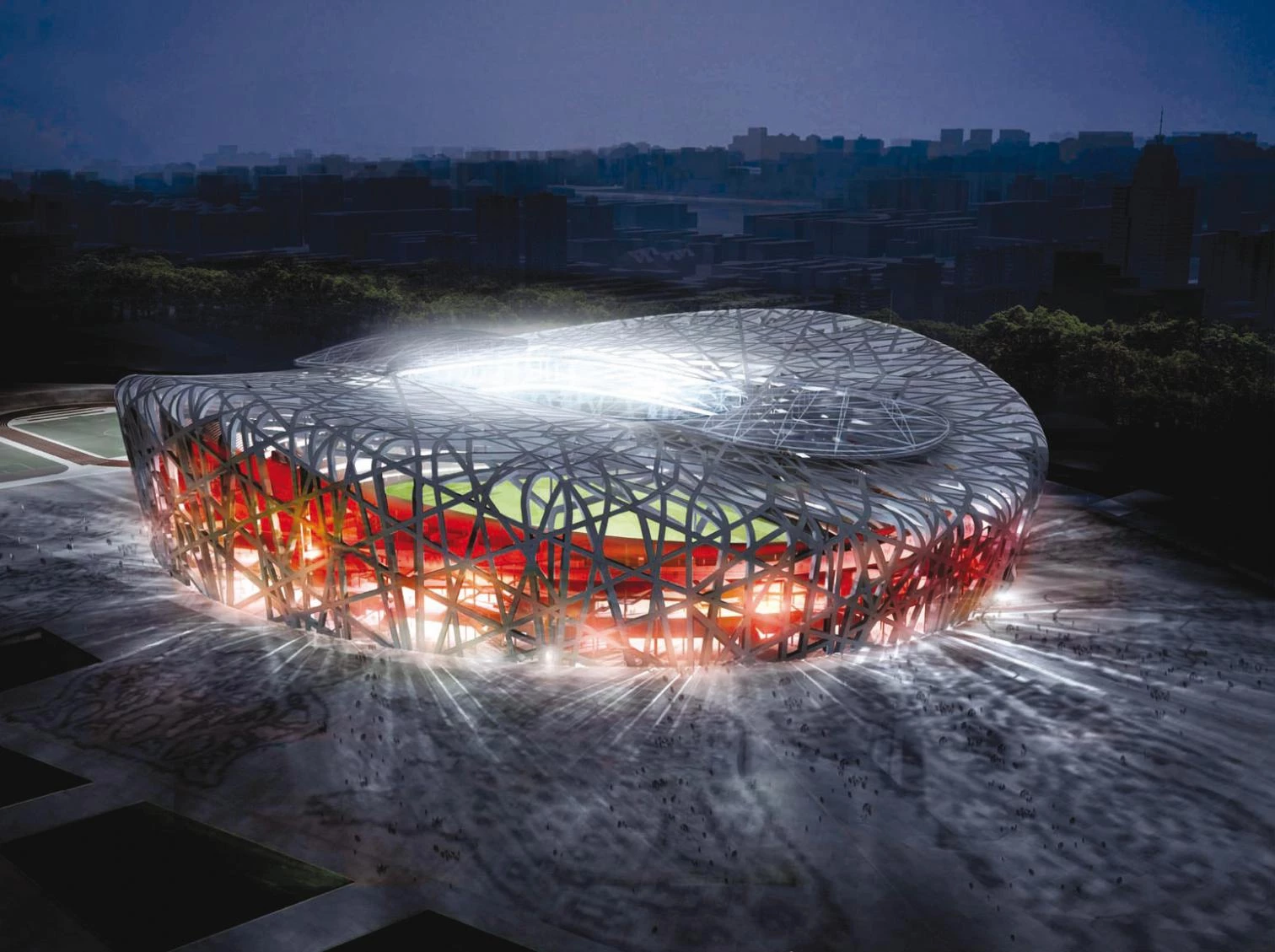

While the UN tried to dissuade the US from attacking Iraq, Libeskind won the Ground Zero competition (above); and Koolhaas and H&deM each entered the stage of preolympic Beijing with great projects (below).

On the opposite end of the world, Beijing prepared its spectacular entry in the global scene on the occasion of the Olympic Games commissioning two European offices – after two competitions, and in both cases with the intervention of the engineer Cecil Balmond –to design the most important works of the event: the Dutch Rem Koolhaas (defender of an Euro-Asian alliance to face American arrogance) shall build the loop-shaped headquarters of CCTV, the public network broadcasting the Games; and the Swiss Herzog & de Meuron will raise the olympic stadium as a nest woven with steel threads.

Violent Spring

The war on Iraq began in the spring – which also brought the plundering of its cultural and archaeological heritage, in the Fertile Crescent where cities were born – , and its somber consequences took the shine off the season’s architectural awards. The Pritzker Prize to the veteran Jørn Utzon (author of the Sydney Opera House, but also of the Kuwait National Assembly, razed by Saddam Hussein’s troops in 1991) was presented in Madrid in the absence of the awardee, who refused to abandon his Majorcan retreat; the European Mies Award (which went to a small intermodal terminal in Strasbourg), was received in Barcelona by the Iraqi Zaha Hadid, in a year which also witnessed the completion of her first American work in Cincinnati; and the Japanese Praemium Imperiale distinguished her teacher at the Architectural Association, Rem Koolhaas, author of a bar code flag for a Europe that ought to look towards Asia.

The most important architectural award, the Pritzker Prize, fell upon the Dane Jørn Utzon, author of masterpieces like the mythical Sydney Opera House (above). To obtain an equally memorable image, two auditoriums inaugurated in 2003 were designed with sculptural shapes: that of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, by Santiago Calatrava (below), and the Disney Hall in Los Angeles, by Frank Gehry (below).

His colleagues in Beijing, Herzog & de Meuron, inaugurated in Tokyo a store for Prada (another shared client), completed in Basel an innovative gallery (the Schaulager, for storage and exhibition purposes at once), and received the British Stirling Prize for their Laban Dance Centre in London. But, just as it would happen later with the Gold Medal of the Royal Institute of British Architects to Rafael Moneo, the Alvar Aalto medal to the Colombian Rogelio Salmona, or the Spanish awards to Víctor López Cotelo, Alejandro Zaera or Mansilla & Tuñón, the celebration of openings or prizes were affected by the year’s convulse climate.

A Somber Summer

Urbanism was the talk of the summer, both for the fallout of Madrid’s regional election, which had to be repeated after a scandal of corruption, drawing attention towards the ‘garbage urbanism’ spawned by the property bubble, and for the colossal blackout in America’s East Coast on August 15 – and in Italy a month later –, that urged to think about the technical fragility of the city and the postindustrial territory, in tune with the concern for security sparked by the increase of terrorist attacks in the world.

Meanwhile, on the site of 9-11 where this new urbanism of terror was born, the second anniversary of the catastrophe brought new plans for Ground Zero, incorporating the British Norman Foster, the French Jean Nouvel (authors of the shell-shaped skyscrapers going up in London and Barcelona respectively) and the Japanese Fumihiko Maki for the projects of the towers – the taller one of them had been previously commissioned to the American David Childs, of SOM –, and the Spaniard Santiago Calatrava for the design of the transport hub; all decisions that cut down the role of the competition winner, Daniel Libeskind, to that of artistic consultant for the complex.

Signs of Autumn

The Valencian Calatrava – whom after living in Zurich and Paris plans to settle in Manhattan, just as Libeskind did leaving Berlin –, was also the protagonist of the first days of autumn, with the inauguration of his Auditorium in Tenerife, a large gesture on the edge of the Atlantic whose constructionbegan fifteen years ago, the same as the Disney Hall of Frank Gehry in Los Angeles, another extraordinary example of sculptural work in the tradition of Utzon’s Sydney Opera and his own Guggenheim in Bilbao. In contrast with these two spectacular auditoriums, that of Francisco Mangado in Pamplona shows a model of restful and urban architecture, perhaps metaphor of the civil serenity that is essential in a Spain tensioned by the nationalist demands of the Basque Country and Catalonia.

In a Europe still divided by the Iraq war, the year comes to an end in the symbolic scenario of Berlin, where Rem Koolhaas has inaugurated the Dutch embassy and an exhibition at the Neue Nationalgalerie –coinciding with the completion of his campus center in Chicago’s IIT, another mythical work by Mies – that hopes to express the political sensibility of architecture, in agitated times marked by the strength of signs and the signs of strength.