Urban Exorcisms

Skyscrapers express the growing arrogance of political and economic power, in an unequal and fragmented society that worships success and fame.

Architecture has gone from spectacle to scandal. Whether as individual projects or as mass urban developments, it is tainted with suspicions of bribery, making philosophers revive the old specter of the Faustian pact between architecture and power. Stars of the sector are associated with satraps and infantry professionals appear in the company of dubious councilors and sure com-mission agents. Economic growth nourishes the current flowering of emblematic skyscrapers and totemic buildings while the real estate boom transforms the territory into an indifferent magma, and this mix of symbolic screams and financial whispers creates a city that we no longer recognize as our own. Yet this at once iconic and anonymous urbanity is a faithful portrait of a prosperous and superficial society that flatly refuses to see itself reflected in the dark mirror of the everyday city. The media uses the terms ‘speculation’ and ‘corruption’as hypnotic mantras that conceal the structural legitimacy of most urban developments, and meanwhile judges officiate preelectoral exorcisms that pretend to shoo away the demons and miasmas of a healthy, robust social body, but neither the media nor the judges feel in any way responsible for that Moloch of concrete that our very own desires have brought about.

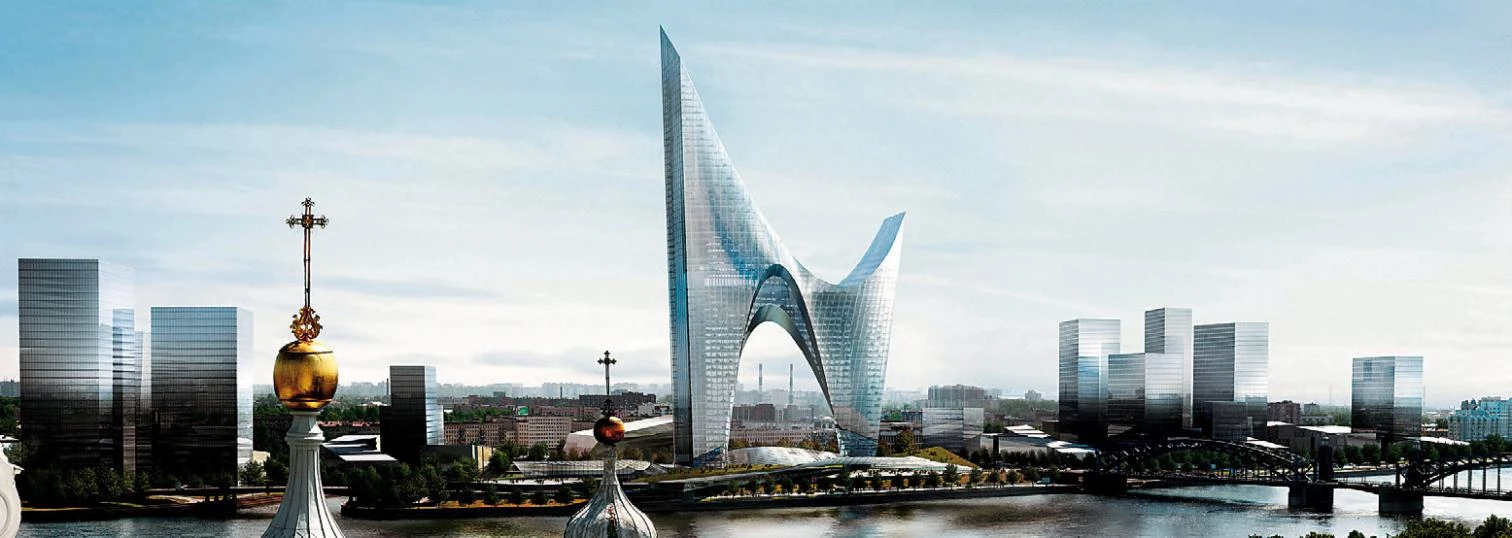

Facing historical centers,Pelli’s tower for the Savings Banks of Seville and that of RMJM for Gazprom in St Petersburg (where OMA, H&deM and Libeskind also participated) evidence the mediocre quality of the new crop of icons of power.

Yes, we have the city that we wanted, and maybe also the one we deserved. Molded by huge historic forces, demographic and technical, that politics can hardly channel and architecture simply makes visible, the contemporary city is not a voluntary geography, but the built expression of what we are. Whining at the material manifestation of financial power or being scandalized by the indiscriminate spread of asphalt is as hypocritical and futile as attacking the pharaohs for building pyramids or deploring the destruction of the coast where we have bought an apartment. An unequal society that worships Mammoth and loves celebrity cannot cry about contrasts emerging in the urban profile, and a hedonist society that pursues personal satisfaction with narcissist self-absorption has no right to censure the fact that the public domain has been utterly gutted by a myriad individual appetites. Our horizontal Babel is the result of humanity’s becoming savage and those who go about preaching liberalization as a panacea prefer to ignore the idea that we may not need more liberty, but less. The crises of the city are settled not as much in the law courts as in the court of public opinion, a forum now deafened by media addicted to sensationalism that take scandal as a variety of spectacle.

Vladimir Putin’s desire to put the Gazprom headquarters in his native St Petersburg, a skycraper to dwarf the Smolny cathedral across the Neva River, is as explicable as the Sevillian savings bank’s determination to build on the edge of the Guadalquivir a tower twice the height of the Giralda. Russia flaunts the energy muscle with which it intimidates the European Union or the ex-Soviet republics in the same way that Seville asserts itself, over Málaga, as Andalusia’s economic capital: erecting giants in historic cities and using companies controlled by political power for the purpose. Both along the Neva and along the Guadalquivir, architects are performers in urban dramas whose plots they do not write, however much they offer gorgeous images or publicity slogans, and whose leading players are really others. A good illustration of this was the indifferent public reaction to the declining of the three foreign architects invited to sit in the jury of the Russian competition, among them Norman Foster, who is now building in Moscow a tower taller than Taipei’s current record-holding one, a circumstance which did not prevent him from giving in St Petersburg a sadly sterile lesson in independence.

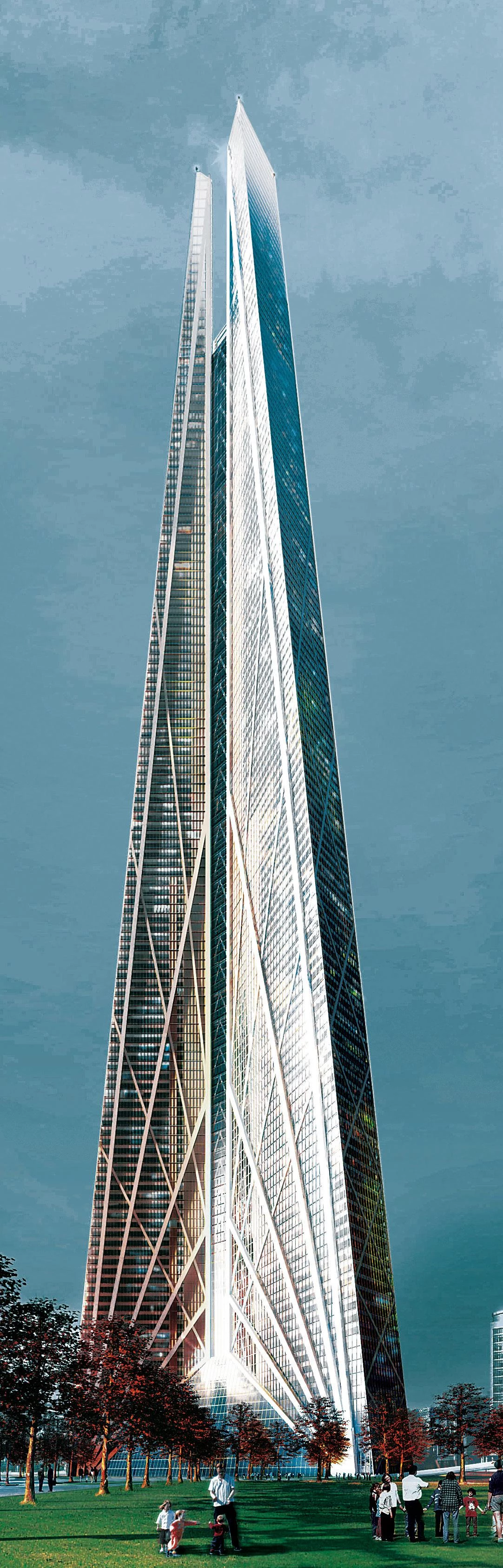

Nothing seems to be able to curb the arrogance of money and oil. In Spain, the real estate boom has produced a new generation of millionaires and a strong group of affluent construction firms that are even expanding toward the energy sector, but elsewhere in the world energy resources are the driving engine of the urban explosion. Dubai, for example, which boasts about using a fourth of the planet’s large cranes, had two skyscrapers in 1999, has twenty today, and will have ninety in 2012: a formidable growth spurt propelled by the Gulf wells and channeled through companies backed by the government, which hopes to turn the city into a financial center with this Manhattan of the desert, where the tower that is supposed to beat Taipei and Moscow in the height race is currently underway. It is also oil that is behind the construction boom of places as remote as Astana, the new capital of Kazakhstan, in the frozen steppes of Central Asia, where Foster, again, has opened a monumental Pyramid of Peace and is busy with an entertainment center, complete with a golf course, a beach, and artificial climate, underneath a colossal tent. Another is the new business center of Khartoum where the White and the Blue Nile meet, the largest complex ever to go up in Africa, crowned by the headquarters of the two companies that extract Sudanese oil for Chinese markets.

The urban tidal wave produced by accelerated prosperity, which is radically transforming the planet’s landscapes, has also dragged architects, and many of them will be reluctant to express objections. To flirt with Putin, the leader of a superpower that is renovating old despotic ways, yet whose favors Angela Merkel and Jacques Chirac compete for? To work for Nursultan Nazarbayev, the dictatorial, messianic Kazakh president, but who is received without qualms by both the Queen of England and the King of Spain? To build for a Sudanese regime that is at war with its own people and is responsible for the Darfur massacres, but whose oil protects it from international ostracism? These are questions that have no answers, because the Manichaean way in which they are formulated serves to lay bare a realpolitik that excludes clauses of conscience, and that has turned global governance into a comforting fiction loudly undressed by the climate crisis. And things are not too different in our own garden. What makes it even worse here is that the unending, useless disputes render it hard to pursue even our own selfish national interests in the muddled ground of an unruly planet.

The best global office, Foster and Partners, reaches with its works the whole planet, from the Moscow tower (below) to the Siberia skyscraper or the huge entertainment center in Astana, capital of Kazakhstan (below).

Whether they build for tyrants or contribute to unsustainable suburbanization, architects have as scarce control over urban mutations as corrupt politicians or greedy developers. In Spain, most of the works that do harm to us, most of the buildings that offend us, and most of the developments that demoralize us are sadly and predictably legal. They are approved by democratic institutions, designed by qualified professionals, and commissioned by companies whose profit motives can only be called legitimate. True, we shape our cities and thereafter they shape us. But the cities we now have cause us so much anxiety that we need to seek the origin of the malaise in deviations or pathologies of the system, and we prefer to attribute ultimate responsibility for the disease to a pack of rogues, crooks and racketeers, in the hope that the purifying task of judges will drain the social organism of mephitic humors. However, it is doubtful that the fight against urbanistic corruption can alone make for a better city. We need other laws, and we especially need a framework of values that does not place unchecked individualism at the center of history, because the cupiditas aedificatoria that nourishes the massive construction of the territory belongs to our hearts and our minds. Paraphrasing the Borges of A New Refutation of Time, the city is a tiger which tears us apart, but we are the tiger.