The Empire of the Trivial

On the second anniversary of 9-11, Ground Zero completes its roster of architects: New York shall heal its wounds with predictable scenographies.

Two years ago , the architect Mohamed Atta changed the world. At the head of 19 suicidal youths, he hit the heart of the empire with such trag-ic and sublime precision that his terrorist act must be used as an esthetic bar for judging the recon-struction of the devastated zone. Both the historic importance of the attack and the cruel perfection of its execution call for an architectural response of similar symbolic caliber, and the public attention the process has received testifies to the expectations aroused. But what is taking shape in Manhattan falls far short of that dramatic level. It seems more like a surrender to the real estate interests of the de-veloper Larry Silverstein and the political demands of state governor George Pataki: on the site of the WTC, the pain and humiliation of 9-11 has only sired commercial plans and trivial scenographies.

Libeskind managed to cap the commission of the century waving the flag, but real estate interests have demoted him to the role of collaborator of David Childs of SOM, in charge of the project now.

In July, the developer chose David Childs – of SOM, one of the firms that participated in the com-petition for Ground Zero, with a long experience in skycraper building – as architect and project manager for the first tower of the new complex, demoting Daniel Libeskind, whom the governor had designated winner of the competition in February, to the role of collaborator and team member. And in August, the transport hub – a huge underground sta-tion linking several subway lines and the train to New Jersey – fell upon Santiago Calatrava, associated with two American engineering firms, in a decision that while recognizing the Spaniard’s track record in railway infrastructures all the more marginalized the author of Berlin’s Jewish Museum, who in New York has stumbled upon economic forces far more powerful than the eddies of German memory and guilt. The Polish American intellectu-al who in spring became the planet’s most popular architect has had a thorny, suffocating summer.

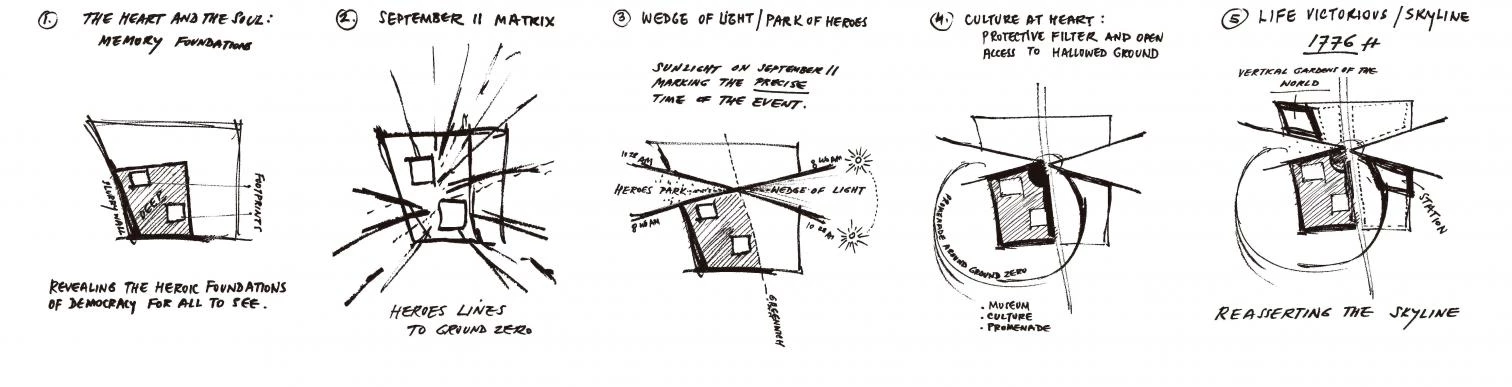

Drawing inspiration from the raised arm of the Statue of Liberty, the Freedom Tower reaches with a garden spire the height of 1,776 feet, to commemorate the year of America’s Declaration of Independence.

During the selection process, Libeskind had sur-prised his colleagues with an unexpected command of the American media mechanisms, something his wife Nina would have been familiar with, having in the past worked as a political scientist and expert in electoral campaigns. Carried shoulder-high by two public relations companies hired for the purpose, the architect showed up in press conferences, granted interviews, and appeared in television pro-grams ,with the US flag on his lapel, explaining how his project – in a remake of Elia Kazan’s America, America – came from the image of the Statue of Liberty that was inprinted in his retina when he was an adolescent immigrant; how the retaining wall of the Hudson River that had stayed intact and that he pro-posed to leave exposed symbolized the strength of America’s democracy; and how the landscaped tower that crowned the complex rose to 1,776 feet in tribute to the Declaration of Independence.

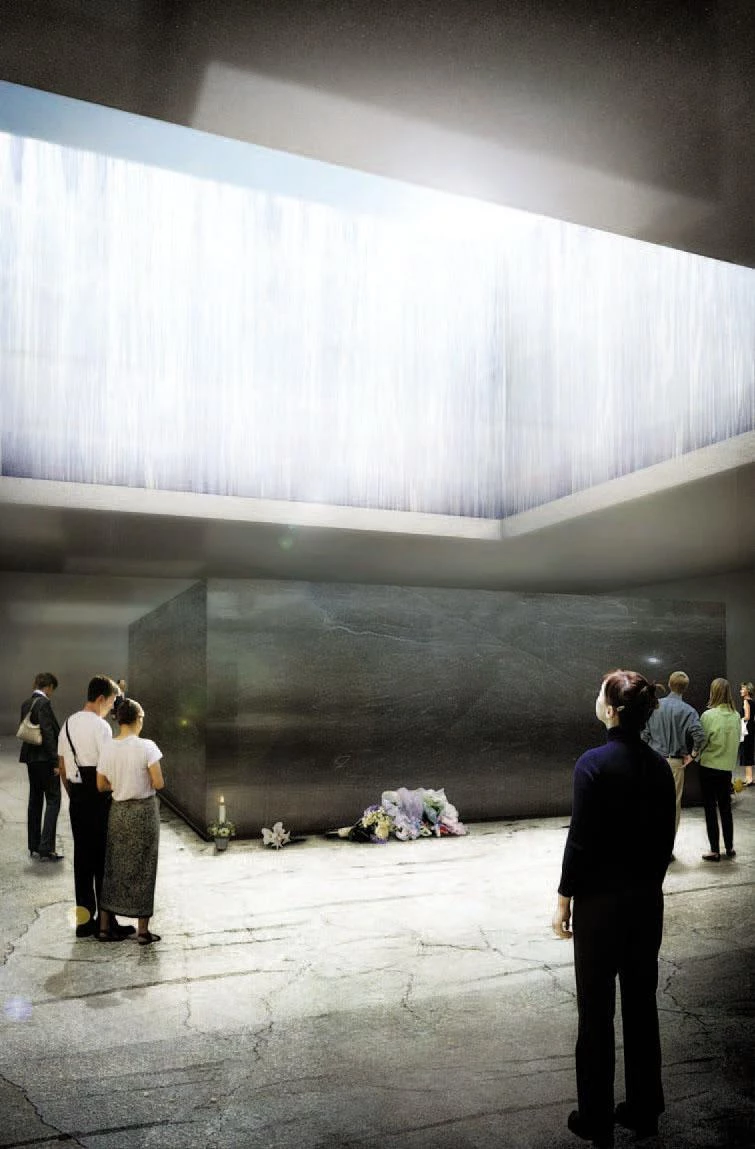

The project of Libeskind reaches its emotional peak in the presence of the original retaining wall of the towers (above), and proves to be schematic and predictable in the rest of the buildings that make up the complex (below).

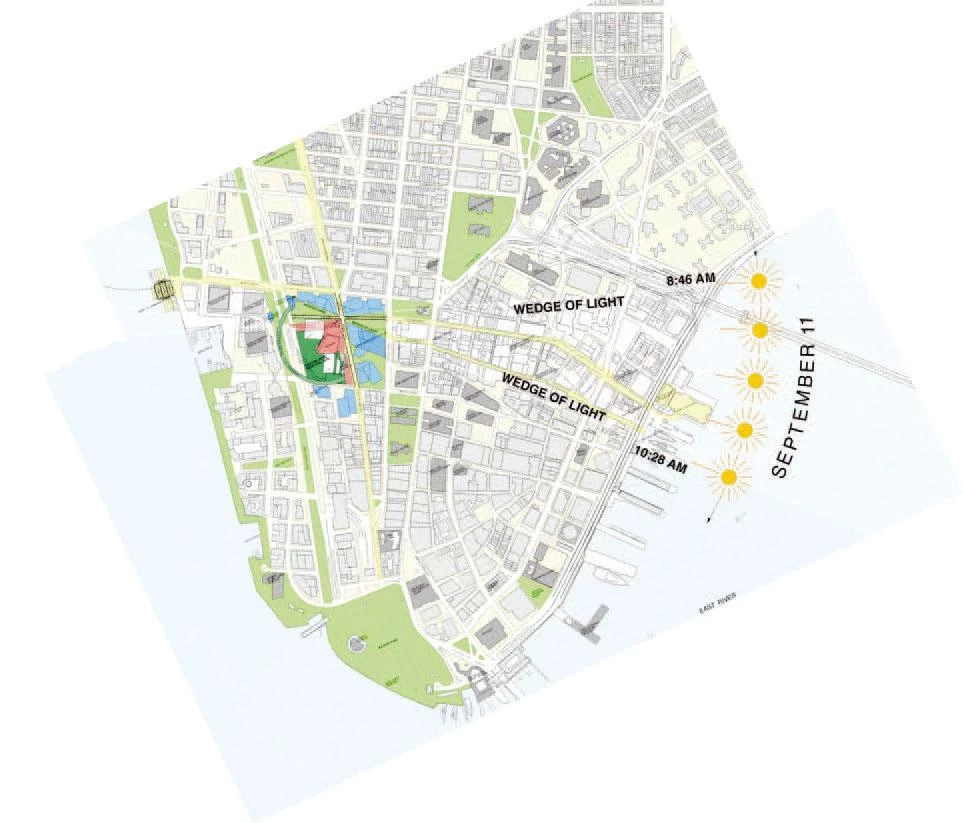

But New York is worth all that, and Libeskind’s jingoistic behavior at a time when the country pre-pared to invade Irak is scandalous only to those who have not seen other architects obtaining commissions after proclaiming undying devotion to Joan of Arc, Manchester United or sushi. More censurable was the inconsistency and superficiality of the project which, while reaching heartbreaking levels of elegy in the 20 meter deep sunken square beside the stark retaining wall, seemed schematic in the group of faceted towers cut out of the Man-hattan skyline, and capriciously decorative in the facades penetrated by a tangle of diagonals between the pompously named Wedge of Light (defined by the position of the sun in the interim between the two plane crashes) and Park of Heroes (in memory of the firemen). Otherwise, the first revisions had already reduced the depth of the square to 9 meters in order to make room for an underground station, much diminishing the drama of the initial scale, and eliminated the gardens of the giant spire evoking the arm of the Statue of Liberty, decreasing the pro-ject’s utopian and lyrical élan.

The Spaniard Santiago Calatrava was chosen to build the underground transportation hub (above); for their part, Michael Arad and Peter Walker won the massively entered competition to raise a memorial (below).

With SOM being assigned the first skyscraper, inevitably named Freedom Tower (which by reaching 1,776 feet – 541 meters – in height allows the developers to claim to be raising the world’s tallest), it seems safe to guess that Libeskind will be limit-ed to cosmetic functions in the work above-ground. And after the appointment for the station of someone as characteristic in his architectural language as Calatrava, we can foresee that the winner of the competition will also be excluded from the underground work. The two offices incorporated into the reconstruction project provide a technical and organizational muscle that will sure make Silver-stein’s budgets and Pataki’s deadlines plausible. But it is unlikely that they can correct the incoherence of a complex that has yet to take in a commemorative monument for which 5,200 design teams have submitted entries, and which from the very start has showed the routinary character of a theme park, with diagonals and fractures conven-tionally recalling the marks of the urban and social trauma and a triangulated skeleton elevating its naïf and vacuous patriotism to the heavens.

With his titanic ‘weeping wall’, Libeskind prob-ably dreamt of a New Jerusalem, but New York is now a New Rome, cosmopolitan center of a reticent empire that tarries in the bellicose labyrinths of Irakistan and loses its way in the road maps of the Palestine conflict: the last suicidal imam sacrificed himself after posing for a picture with his children in a Disneyfied kindergarten, and the contrast be-tween the desperation of the downtrodden and the interiorization of the aesthetic codes of the metrop-olis sum up in a shot the perplexing ambiguity of times when violent disorder and smiling trivializa-tion go hand in hand, where enemies are a deck of cards, Bush is a Madelman dressed as a pilot, Sad-dam appears in posters with the bust of Rita Hayworth, and Spain’s expeditionary force crowns its Babylonian camp with the Osborne brandy bull. As if to compensate, Georgia has opened the world’s first theme park about misery, giving the children of the empire the chance to acquaint themselves with the shanties of three continents, confirming that Bradbury and Dalí were sharp in declaring Disney a visionary, and suggesting that Warhol is now no less pertinent than Santiago Serra.

If the Ground Zero project is trivial, it may be because the metabolism of the metropolis requires such a skeptical diet, and we are wrong to expect the sublime force of the heroic. In this empire of senseless signs and insubstantial senses, the ex-hausted figures of New Yorkers stranded on side-walks by the August 15 blackout evoke the theater of extermination in anti-war demonstrations. At the same time, they recall the carpet of corpses that was spread three weeks before in front of the US embassy in Monrovia to clamor for American inter-vention in the Liberian conflict. Whether dead or alive, the bodies of the multitude send out a choral message that contradicts the daily demand of the individual profile. A tattoo shop in Bilbao carries the slogan “personalize your body”, but nowadays a person dilutes in the trademark, and no sign on the skin is more eloquent than a logo: the torso of swimmer David Meca is decorated with transfers of sponsors, the racing driver Fernando Alonso is unrecognizable without his overalls, and the football player David Beckham melts in a metonymical T-shirt. Posh Victoria expresses it well: “we want our own brand”. Meanwhile, reversing the ways of sheikhs building houses in Marbella, the couple has bought a dream villa on a manmade island in Dubai, the same place where SOM is to erect the 580-meter tower that will allow the United Arab Emirates to snatch from New York the height record that SOM itself will give it with the Freedom Tower. The ways of Islam and the empire are inscrutable.