For 60 plus years, Doshi’s atelier, Vastu-Shilpa, has diligently fashioned a remarkable range of works. Consistently and reliably, they have addressed global concerns such as working with the climate, environmental degradation, resource depletion, earthquake hazards, and so on, and that too before these issues came to the fore. He employs simple materials, local technologies, and many hands. Most importantly, occupants and users are Doshi’s true compass.

The atelier’s name, Vastu-Shilpa, is revealing. Vastu in Sanskrit means the ‘science of architecture’ or ‘building construction’; it is well described in two classical texts, Mayamata and Manasara, primarily dealing with the cardinal points of building as related to earth, fire, space, water, and wind. Shilpa is ‘arts and crafts - sculpture.’ When used together, Shilpa acquires a broader meaning because working with craftspeople and artisans, what the architect sculpts is embodied into an edifice. Hence, Vastu-Shilpa is a potent idea as well as a process-driven concept.

Doshi worked from 1951 to 1954 in the Paris studio of Le Corbusier. He returned to India to supervise the great master’s Indian projects. Working on seminal commissions such as the Millowners’ Association Building, Sanskar Kendra or Municipal Museum, and residences of Ahmedabad’s wealthy merchants gave the young architect access to influential people in his adopted city. The millowners had consequentially supported Gandhi’s struggle for India’s independence and were embarking on building a free and democratic country. Inspiring times for Doshi to establish his own practice, which he did in 1956, continuing to supervise Le Corbusier’s Ahmedabad projects. Notably, while working with one of the most individualistic modernist practices of the 20th century, perhaps ever, Doshi christened his nascent practice with the Hindu traditional connotation: Vastu-Shilpa.

A close disciple of Le Corbusier, Doshi is a rebel at heart, a contrast to his gentle and accessible manner. He was silently challenging the notion of an architect master-builder, for in India, buildings are crafted and built in collaboration with a vast array of artisans. It was also an ode to his family tradition: Doshi, born and raised in Pune, hails from an extended Hindu family of craftsmen – carpenters, furniture makers for generations. I have observed them interacting, and remain convinced he owes his uncanny sense of visual proportion, level, and alignment to the family traditions.

Housing is the Key

Doshi’s early career comprised a couple of low-cost housing projects which in my opinion were pivotal: the Ahmedabad Textile Industry Research Association (ATIRA) and the Physical Research Laboratory (PRL) staff housing. In the 1950’s, high-energy input materials like steel and cement were scarce. Doshi took the opportunity to experiment with inexpensive local materials like bricks and hollow clay tiles. In the ATIRA housing, he used parallel loadbearing brick walls and segmental vaults to fashion attractive row housing with front and back verandahs, essentially outdoor living spaces for domestic activities, including sleeping at night on roofs and in gardens in tropical climate. Projecting vaults cover platforms, protect transitional spaces, and enhance a sense of place and welcome; a modern take on the traditional pattern of living. This practice and range of devices he has continually and successfully used and refined. These relatively small projects prepared him for larger housing projects, mostly company townships.

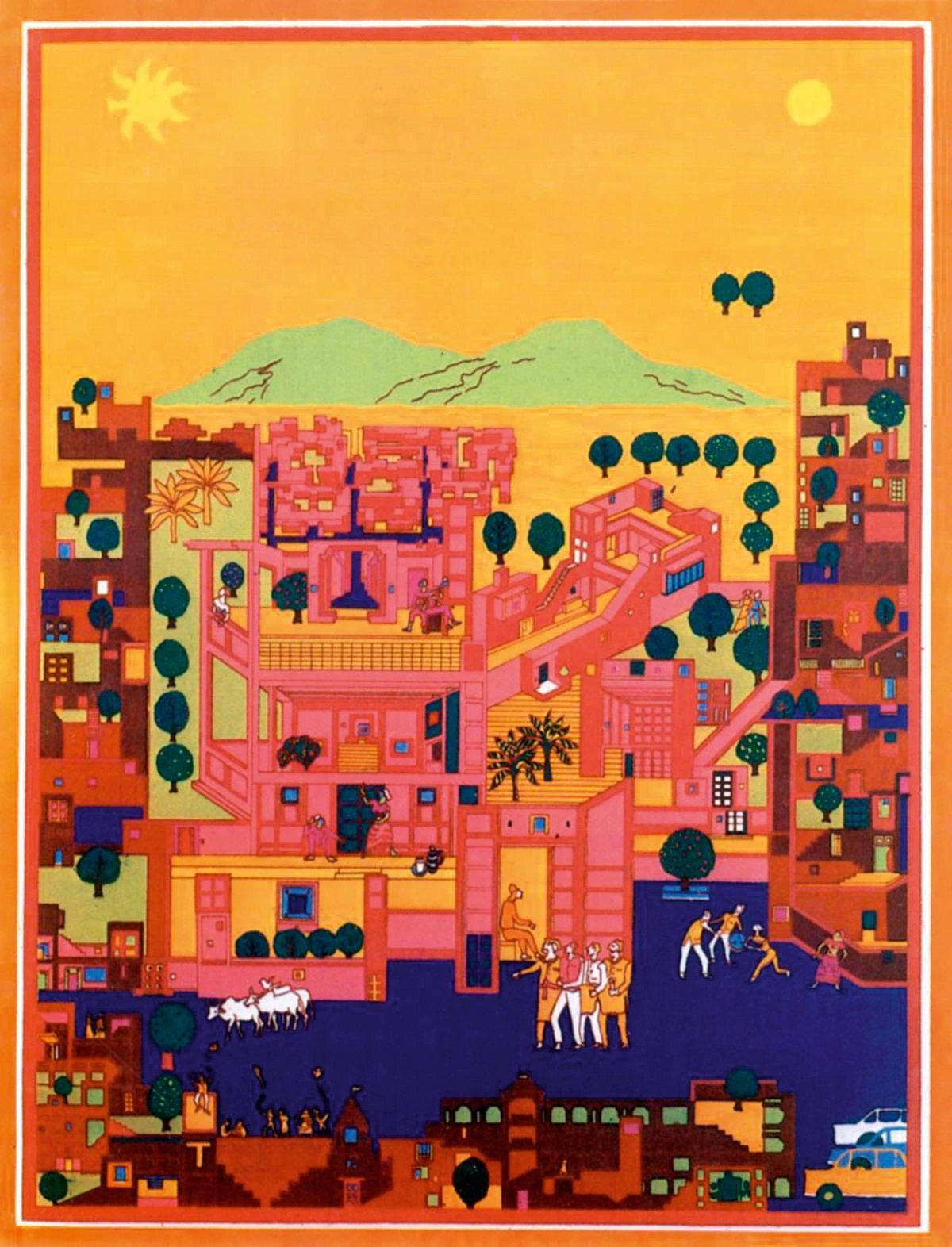

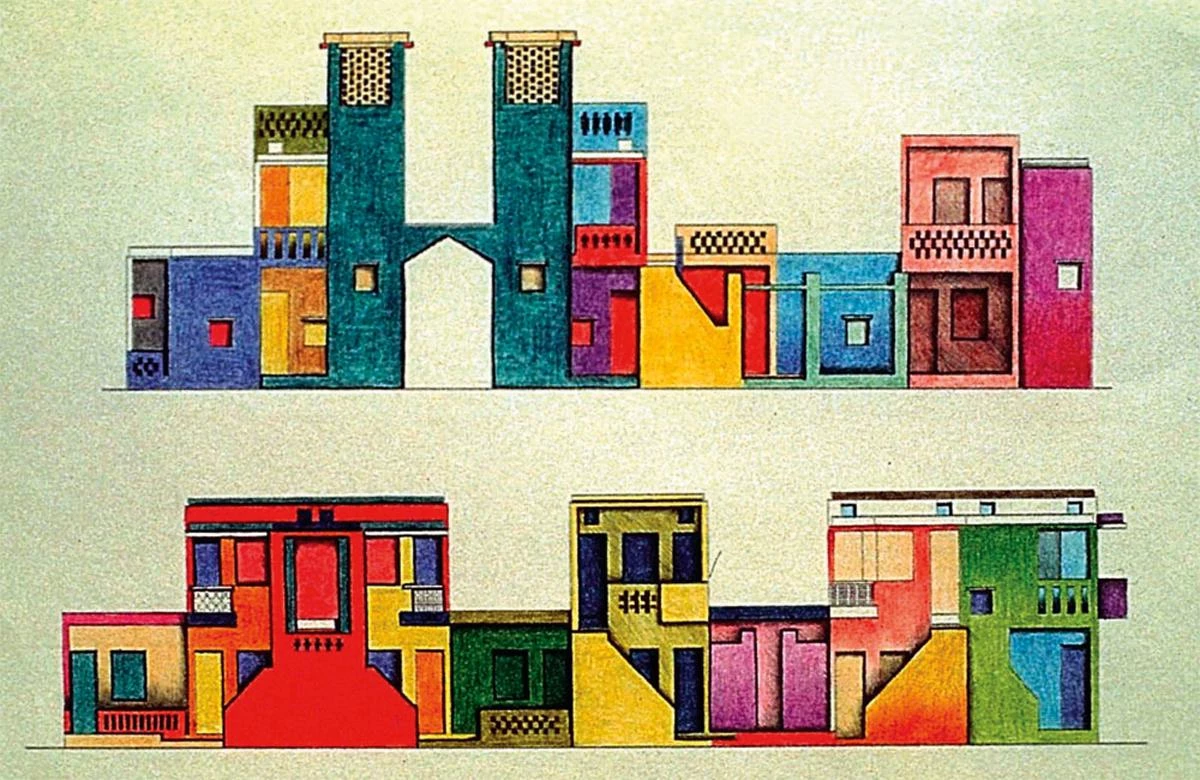

The company towns are like urban microcosms. Although they comprise different income groups, from general manager to peon and all other income categories in between, townships are designed as self-sufficient communities of 200 to 2,000 families sharing facilities and amenities. Homes and clusters of homes are additive. Combined, they form neighborhoods. Ultimately, Doshi proposes low-rise (one to two stories), high-density layouts which are pedestrian-oriented and clearly inspired in traditional cities. Concerns of climate are paramount, hence cross ventilation, protection from the sun, and walkability.

Inherently the company townships have one major handicap. Like Chandigarh, these communities are conceived by and for people working for the formal sector, either the government or a company. This leaves out serving classes like vendors and hawkers, service providers, and laborers, the other half of urban society. A considerable part of the population is left out without housing options. This resulted in widespread growth of informal housing or slums across India.

In 1978, to do research in environmental design and low-cost housing, Doshi set up the Vastu-Shilpa Foundation in parallel with his design practice. The Vastu-Shilpa Foundation works as a link between academics and professionals, developing contextually relevant norms and standards with emphasis on habitat design, sustainable development, appropriate technologies, heritage conservation, and so on. When Doshi received the biggest housing design commission of his life, Aranya, a low-cost project in Indore, in central India, he opted to carry it out under the auspices of the foundation.

Doshi used the scarcity of high-energy-cost construction materials, such as steel and cement, as a pretext to conduct research on cheap local solutions, including bricks and lightweight ceramic pieces.

The project was significant because it was to house about 7,000 families on an 80-hectare site and 60% of the housing was reserved for very poor inhabitants. It was projected for a population of 65,000. Today the population has surpassed 80,000. I collaborated with him on the project. We did studies on Indore’s informal settlements, documented in a series of publications titled How the Other Half Builds. We showed that squatters develop distinct settlement patterns in response to their lifestyle, spatial requirements, and economic needs. Doshi and his design team responded to these and other findings by creating a framework for housing that users could slowly fill in and build on. The team set up a robust urban and domestic armature which absorbs additions and cumulative changes without losing its identity.

Paths of Experimentation

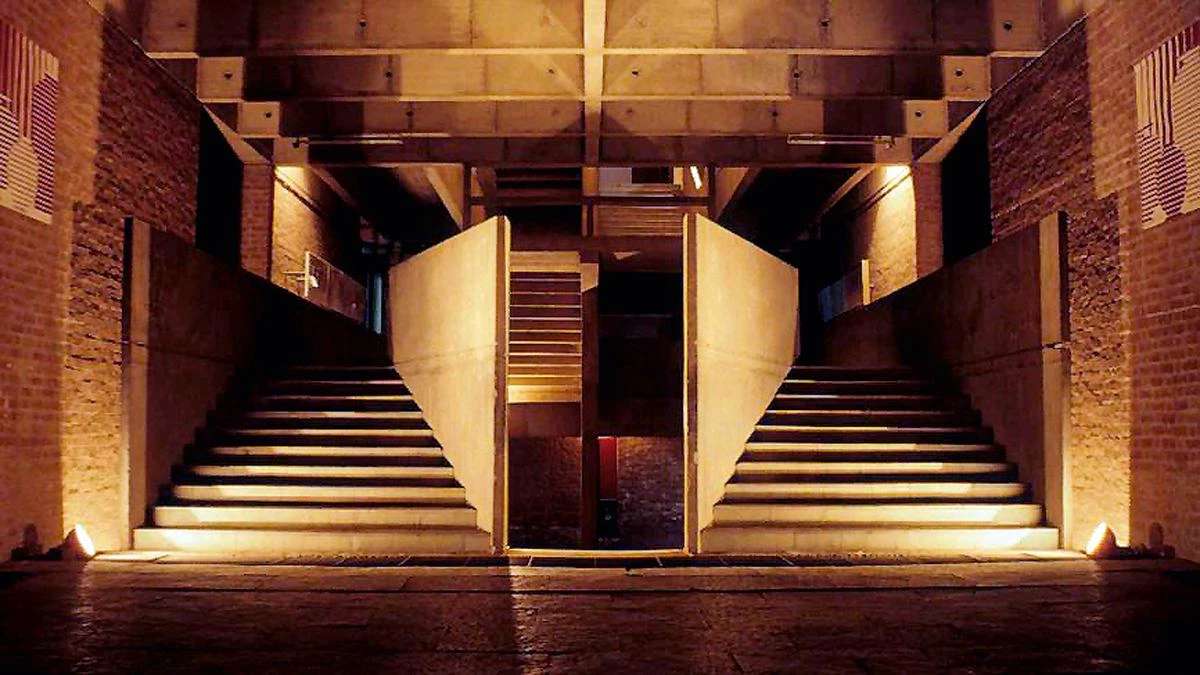

The early dream-come-true projects also set Doshi free on the lifelong path of experimentation. Doshi thrives, seeks out, designs handicaps. He accepted a difficult site for the School of Architecture, now the CEPT University campus, in Ahmedabad. An almost impossible-to-build-on site became the architectural generator of form. Four loadbearing walls were built directly in the trenches of old brick kilns, interlocking studios were stacked on the walls, freeing up the lower level for outdoor classrooms and informal areas essential for the school’s multi-faceted daily life. Care was taken to protect the neem trees, which became places for congregation, and surrounding mounds were landscaped and integrated with the building.

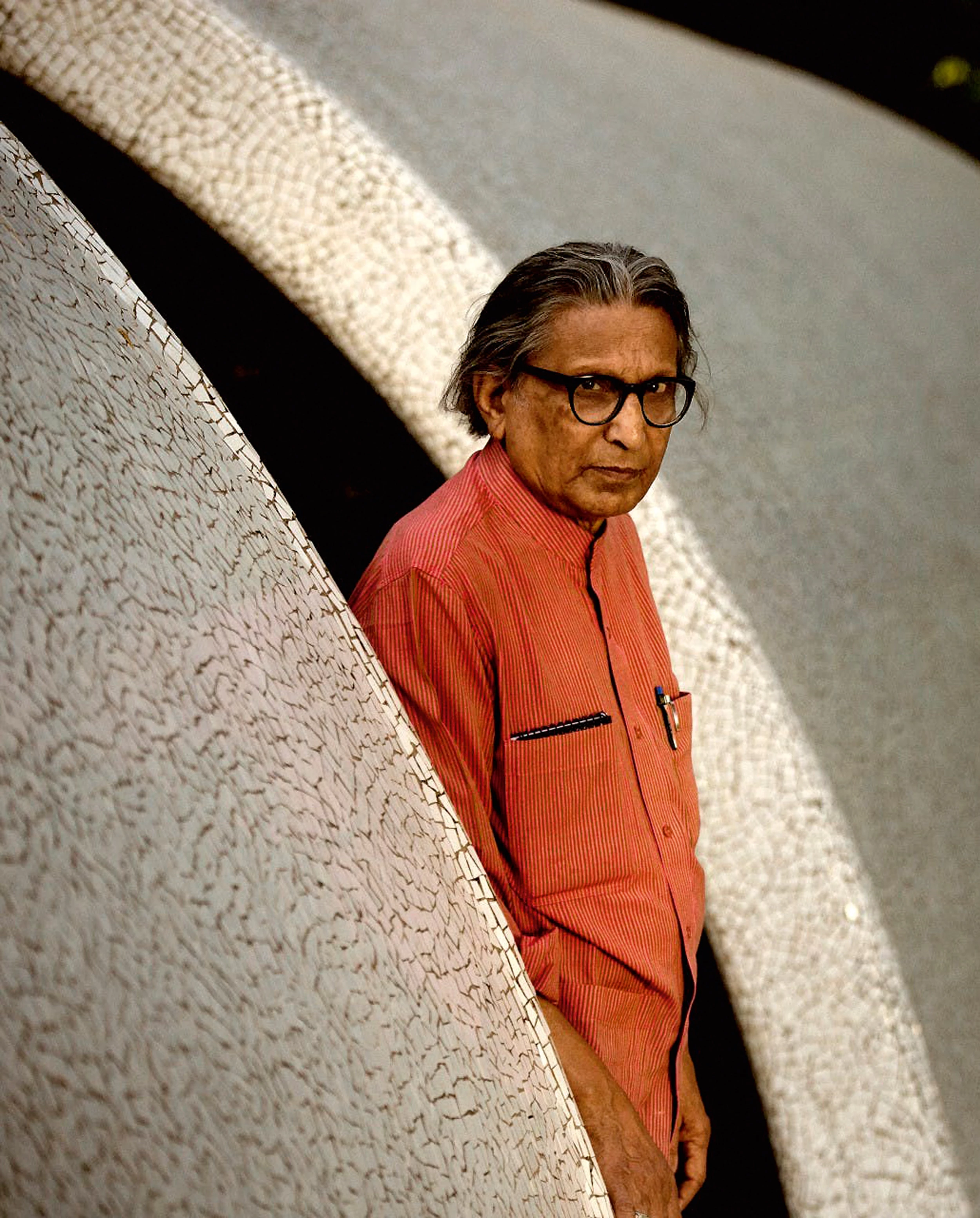

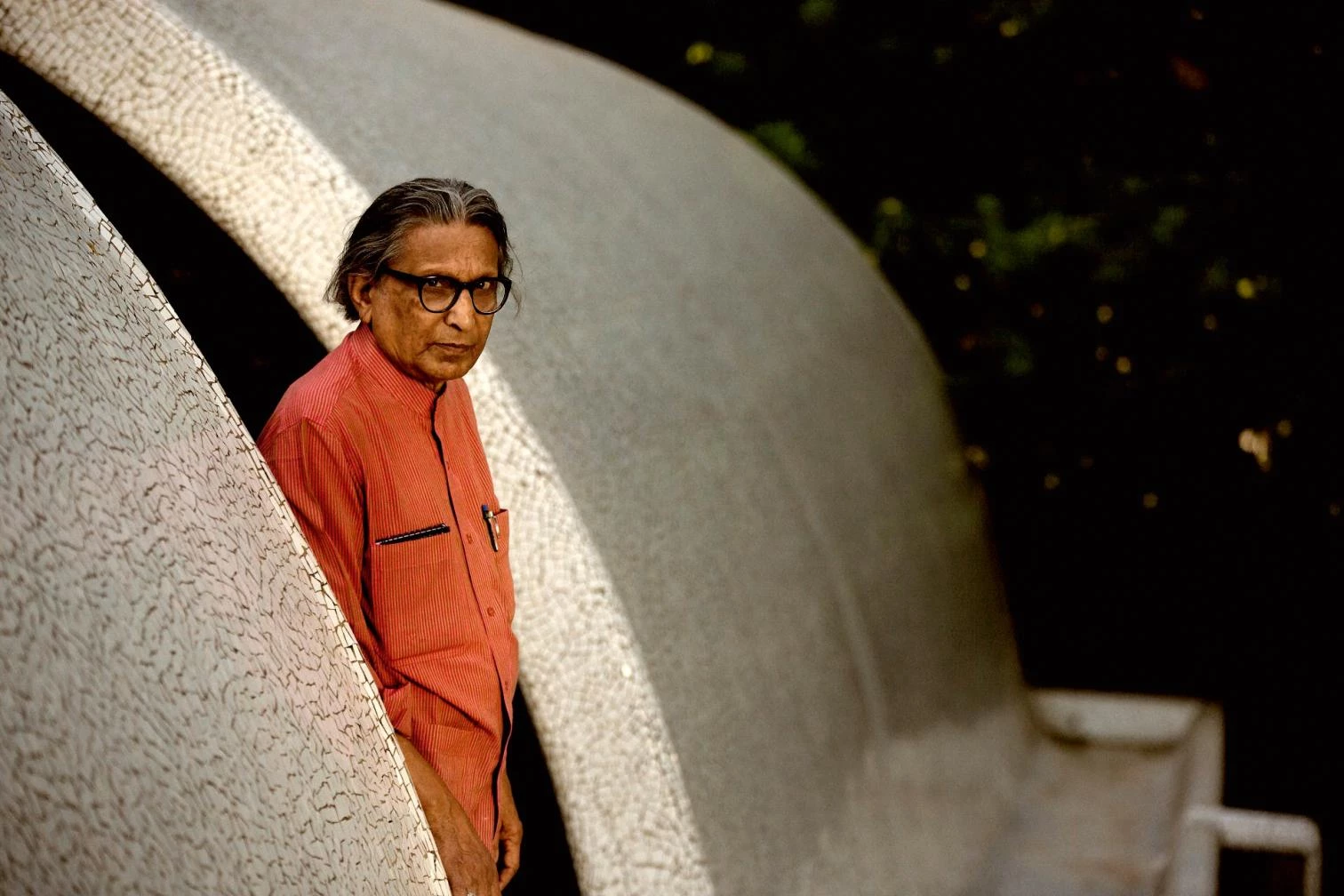

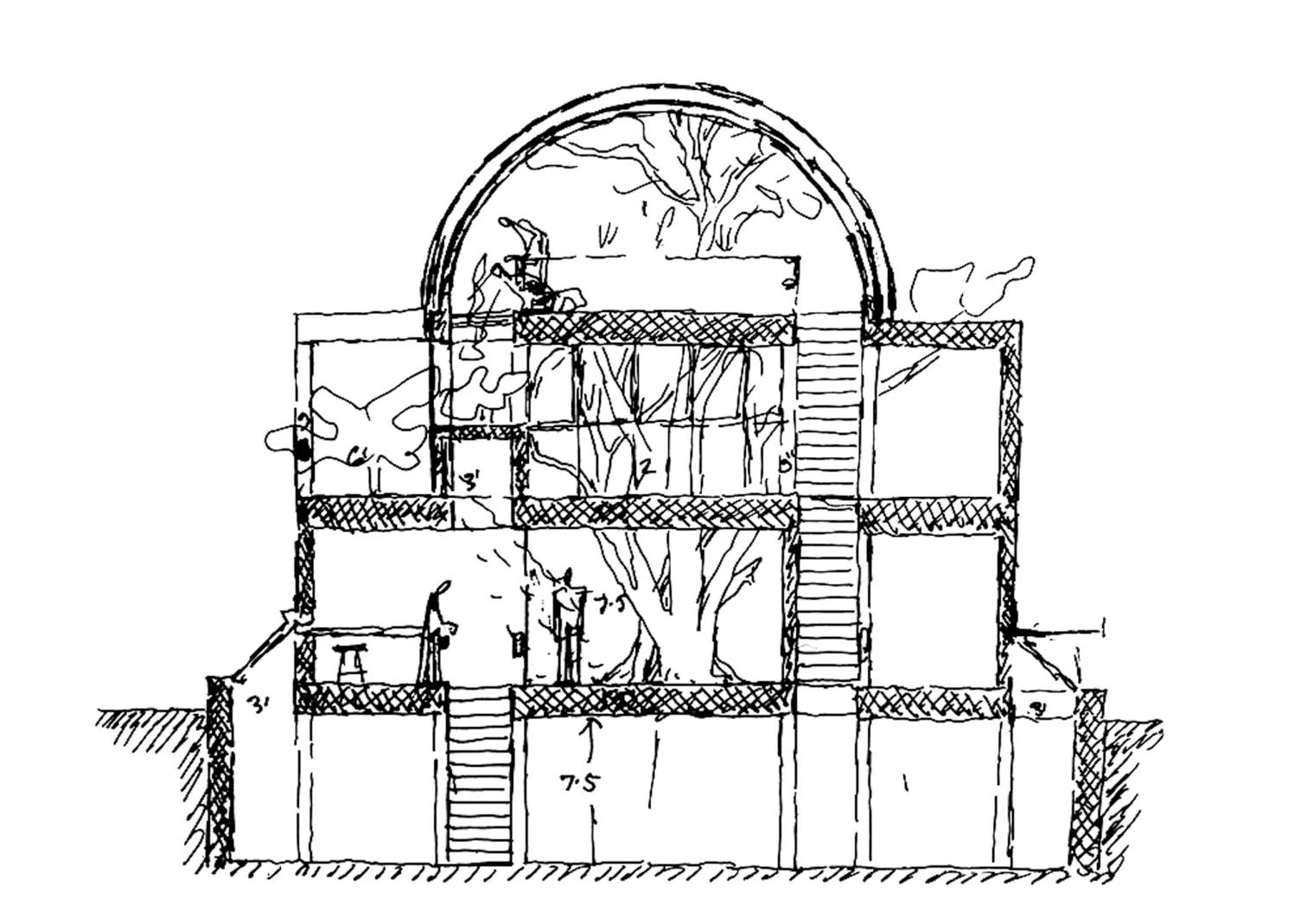

Almost 20 years later, the hollow tile roof from PRL housing made a successful comeback in the form of more refined vault structures of Doshi’s own office, named Sangath, which means moving together on a journey or a pilgrimage. More than an office, it is a place for exchanging ideas. A beautifully landscaped garden, comprising an intimate amphitheater where often the staff can be seen having tea and snacks as if in a public park. The studio space feels monastic; a barrel vault is interrupted in places to stack volumes and allow clerestory light into the workspace; the outside of the vault is covered in broken shards of china mosaic and is sculpted to naturally collect and channel rainwater. The entire experience is calming and magical.

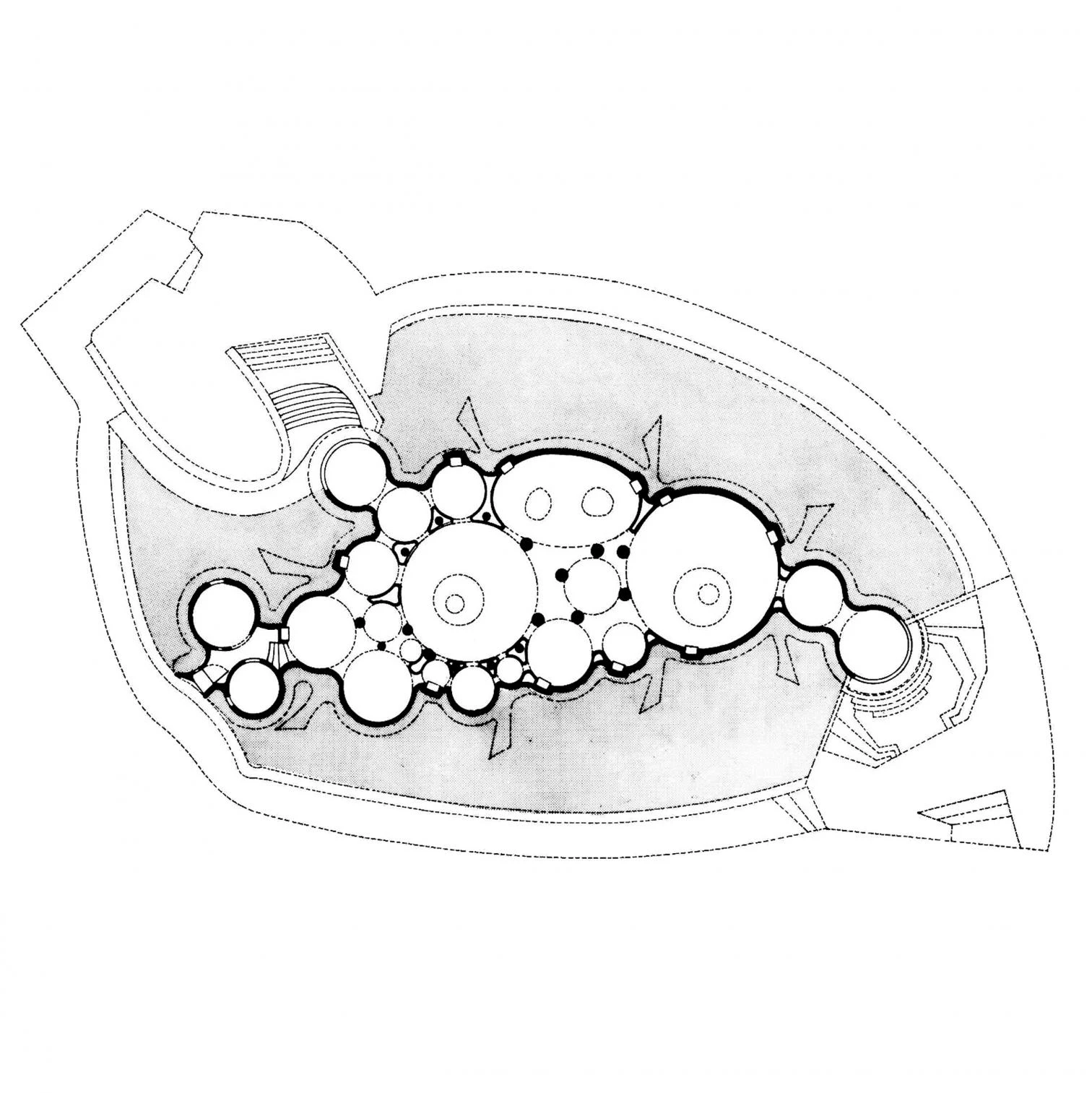

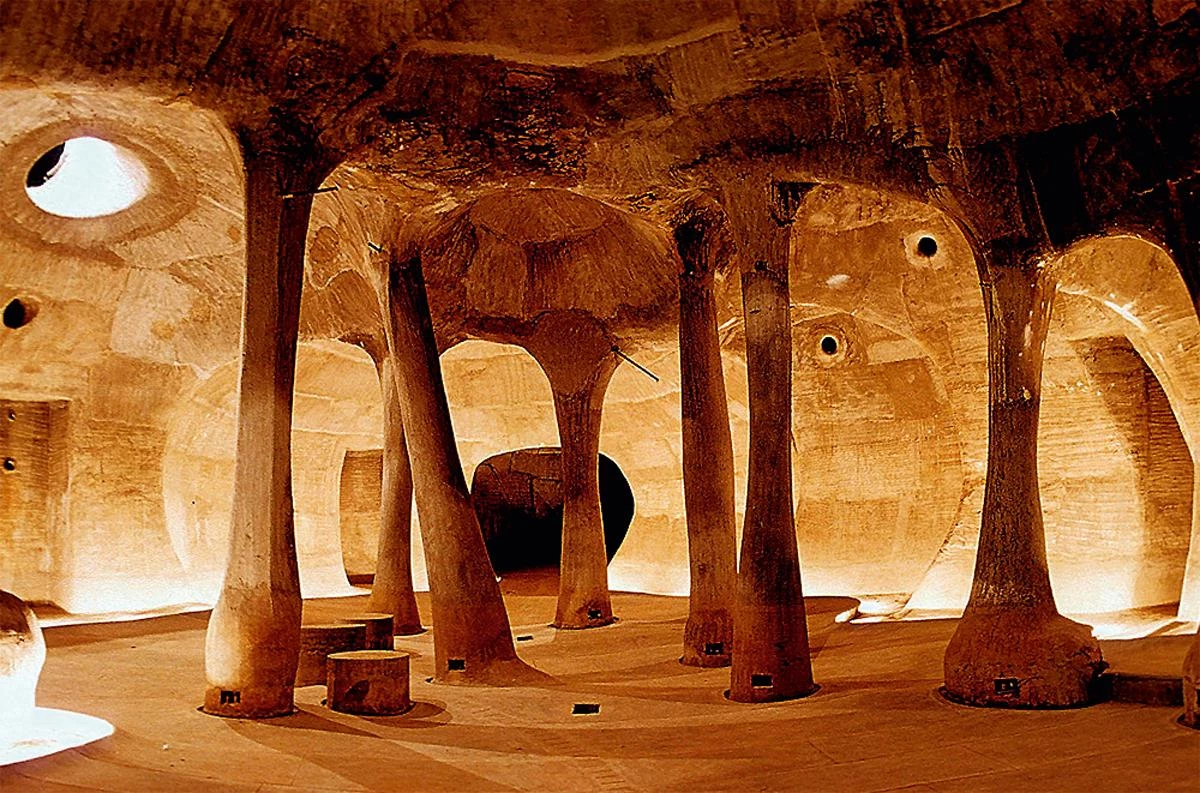

In Sangath, his atelier, Doshi reinterprets modern tradition; in both the Amdavad ni Gufa Art Gallery and the Indian Institute of Management he resorts to an organicist language rooted in local building culture.

Local is Global

In the present climate of growing nationalism, the selection of Doshi as a Pritzker laureate could be misread, as he has practiced only in his native land. Let us remember that his collaborations with Le Corbusier and numerous other international architects and institutions tampered both the local and the global perception of architecture. He invited Louis Kahn to work in India. Kahn’s housing for the IIM staff and Doshi’s CEPT campus show how they influenced each other. It is via such continuous international exchange of ideas that Doshi reshaped the architecture of India as a leading practitioner. In the era of signature architects and their allied global practices that never sleep, Doshi’s focused practice is special. His architecture is rooted in time and place – grows out of it – without being provincial. He has chosen to work on important and urgent local problems, such as housing for the poor, and framed these issues in such a way that he is able to address consequential global issues of health, economic empowerment, spatial justice, livable cities, and so on. Furthermore, like great terroir food, his architecture pleases and can be enjoyed and can inspire globally.

Vikram Bhatt es profesor de arquitectura y urbanismo en la McGill University de Montreal.