Piano lontano

Renzo Piano has achieved worldwide success while maintaining the artisan approach shown by his last projects and works in the United States and Europe.

He gets hundreds of offers a year, but accepts only three or four. “A project lasts an average of five years, and it is impossible to personally tackle more than twenty at a time”. In his Genoa studio at Punta Nave, each one of the twenty works is held by a pin on the wall across his desk, where sketches, drawings, and working details are superposed on one another to give the architect an abbreviated panorama of how the project is progressing. When not traveling to check on job sites, Renzo Piano divides his time between his Paris and Genoa studios, two offices reigned by a luminous order and a contained scale – neither employing more than 50 persons – that make it possible to maintain the family atmosphere and close contact with materials characterizing a studio that chose to call itself Building Workshop, and where computers and pencils share the desk with tools and machines used for making prototypes and models. Piano has not let success distort his artisan work method, refusing to expand, declining most commissions or competition invitations, rejecting offers to teach outside of the studio, and limiting his public appearances to two or three a year, these almost always in connection to exhibitions of his work. .

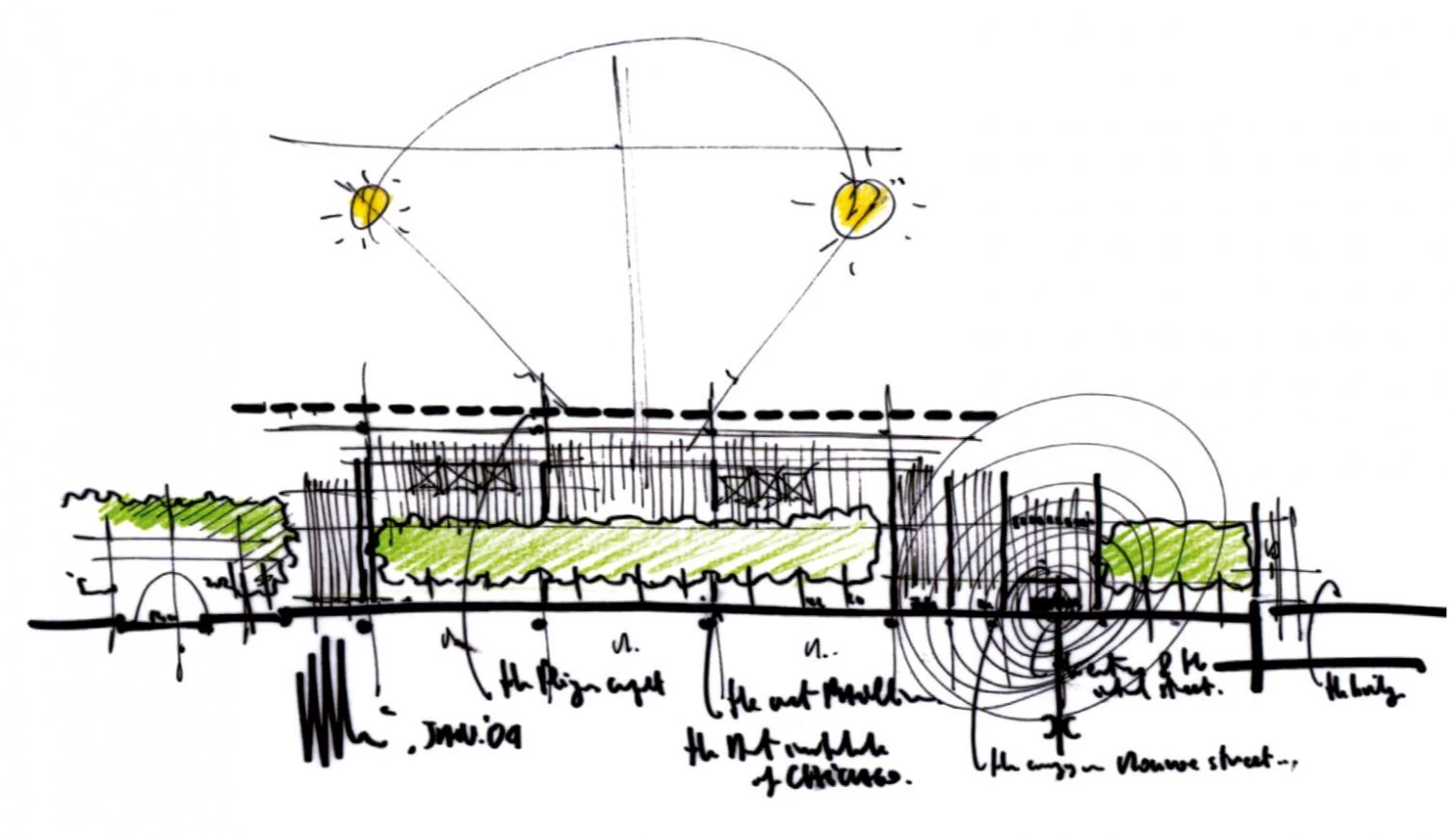

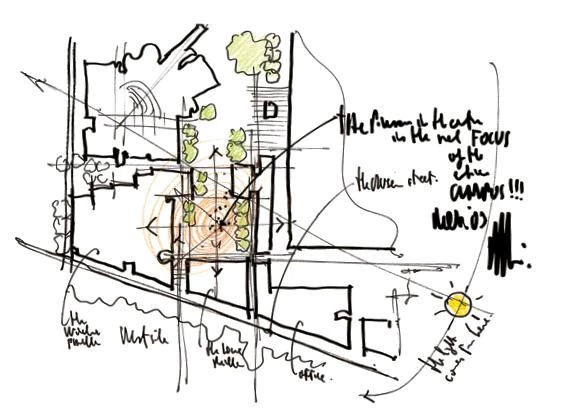

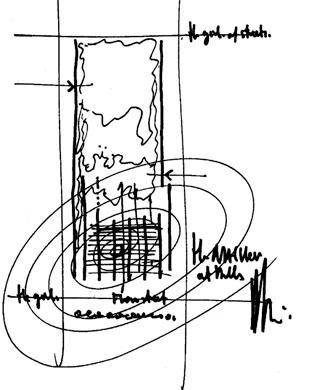

The enlargement of the Chicago Art Institute unites climate, nature and history beneath a light canopy.

Such a reticent attitude has not prevented the Genoan from building all over the world, because his popularity rests precisely on the universality of his language: exact geometries, exquisite details, and luminous spaces. An architecture based on order, construction, and clarity is irresistible, and it is no wonder that his balanced mix of exactitude and inventiveness fascinates clients and colleagues alike. Clients find in Piano a professional approach that reconciles budgets, timetables, and programs with a unanimously acceptable clean aesthetic, and an attention to context and environment that makes it possible to present his projects as socially and ecologically responsible. And colleagues admire the Building Workshop’s ever experimental attitude, which makes each new work an exploration trip, and the technological refinement that manages to combine the pedagogical rigor of assemblages with the tactile sensuality of materials.

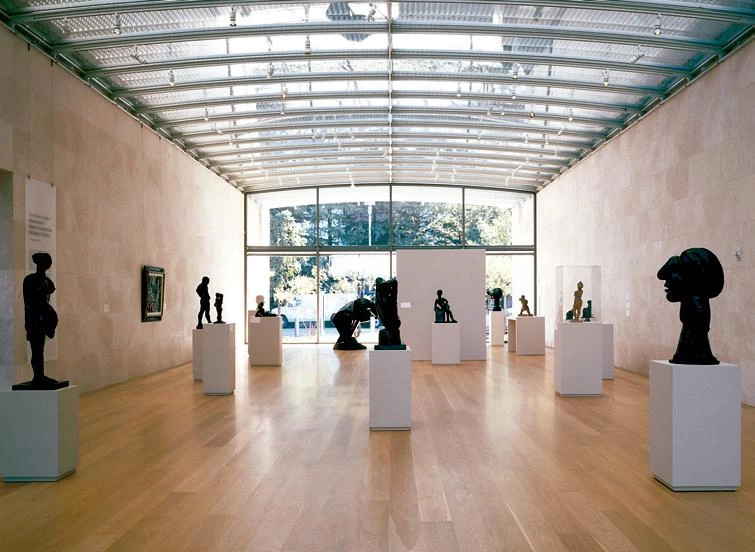

In contrast with the neocorbusian gestures of Meier’s earlier building, the extension of the Atlanta High Museum displays a laconicism that only becomes expressive in the rhythmic gathering of the roof skylights

The Nasher Sculpture Center joins the art park with a pavilion of parallel loadbearing walls and delicate translucent vaults that is visually linked with the garden, bringing to Dallas the experience of Basel’s Beyeler.

A proof of Piano’s popularity among institutional clients is the large number of ongoing projects he has in the United States alone, perhaps the most competitive market. In New York City he is busy with the skyscraper of The New York Times, right on Times Square; the enlargement of the Whitney Museum of Art, a commission significant not only on account of the museum itself but also because of the mythical building by Marcel Breuer that houses it, and which recently got the go-ahead from the exigent board of trustees; the extension of the prestigious Morgan Library, due to open this next spring; and Columbia University’s new campus, situated out in the Bronx and the size of the Manhattan one. In Boston he will be enlarging another museum, the Isabelle Steward Gardner Museum, and though negotiations are currently on hold, in Cambridge he is to do the same for Harvard University’s Fogg Art Museum, for which James Stirling did a first enlargement two decades ago. Also enlargements are his projects for the Chicago Art Institute, construction for which has just begun with a lot of media fanfare; the High Museum in Atlanta, a huge container scheduled to open in the fall; the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco; and, last but not least, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), an important commission in which, as in the Whitney case, he replaces a Rem Koolhaas who could not or would not adapt to the institutions’ functional and financial demands.

The list is indeed impressive and one can understand the malaise of many American architects who, feeling left out, attribute Piano’s success to the desire of the clients to play a sure card – few museums in the past years have been as well-received by both public and the critics as the Genoese architect’s two Texan buildings, the Menil Collection of 1987 in Houston and the Nasher Sculpture Center of 2003 in Dallas. But the long list of works in progress does not justify the bitterness of the Architectural Record, which tags him between question marks as a ‘default architect’, nor the imperious terms in which professionals like Steven Holl recently demanded a share in the Columbia campus commission. But Piano argues that making architecture “simple, subtle, and serene” is neither simple nor risk-free, and other colleagues of the English-speaking world acknowledge this merit of his in generous terms. The last annual survey of The Architects’ Journal showed the Italian to be the living architect whom professionals of Great Britain most admire, before Norman Foster and way ahead of Richard Rogers and Glenn Murcutt, who come in third and fourth. This despite Piano’s having capped London’s most meaty commission, which has just obtained final permission from Livingstone’s mayoralty: a sharp glazed skyscraper that will be Europe’s tallest and that is already commonly known as the “Shard of Glass”.

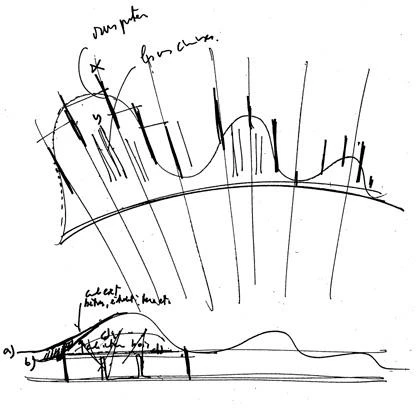

On the outskirts of Bern, near the artist’s tomb, the Zentrum Paul Klee is shaped with three large waves that merge into the landscape and whose scale contrasts with the small size of the works of art displayed inside.

That Piano’s museums do not elude risks is evident in his most recently completed work, three waves of steel in the outskirts of Bern that bring together the work of Paul Klee – an artist who was born in Switzerland and died there, although he never held Swiss citizenship, and who is buried close to the place. Here the Italian architect avoided repeating the silent scheme of his very popular and praised Beyeler Foundation in Basel. Instead he conceived a topographic and sculptural gesture, so memorably unique, that alludes to the undulating terrain of hills and has had as many defenders as detractors. Among the latter is The Sunday Times critic Hugh Pearman, whose chronicle begins in this manner: “I used to think that Renzo Piano was the best international architect in the world. He was not in-your-face showy, like Frank Gehry. Not in thrall to technology, like his old chum Richard Rogers. Not puritanical, like Norman Foster”. But in time he reveals his disappointment, seeing in the Zentrum Paul Klee no empathy with nature, but the formalism typical of works aspiring to be tourist landmarks and city icons, omitting the idea that the three waves, rendered in steel with techniques evoking shipbuilding, are supposed to represent the cut of the relief through the existing road. He also deplores the lack of natural light in the exhibition zones, ignoring the fact that the delicate fragility of the painter’s drawings and watercolors compelled the architect to dispense with the top lighting of his other museum projects. To be sure, the loquacious waves may be an unusual setting for displaying the small works of an intimate, silent artist. Nevertheless, the unexpected emotion elicited by the frozen swell makes the risk of incomprehension worthwhile. An architect who is able to choose his clients can also allow himself to puzzle the critics..