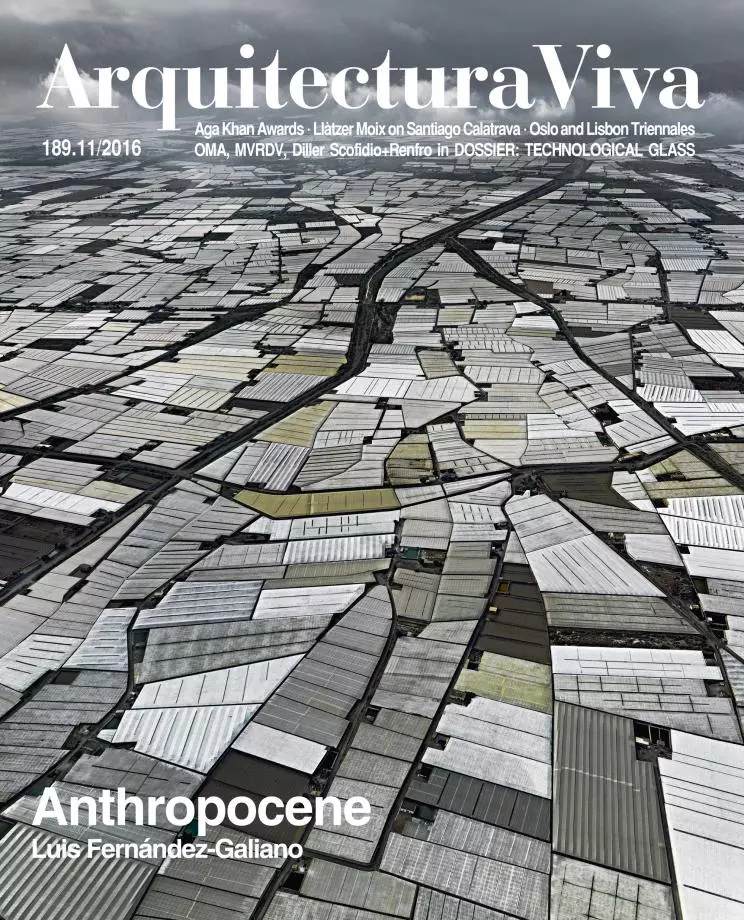

The fourth edition of the Lisbon Architecture Triennale, under the title ‘The Form of Form’, goes back to the foundations of architecture by questioning the origins and consequences of built form.

The sharp drop in commissions brought about by the economic crisis – which hit Europe strongly almost ten years ago – has broadened architecture’s field of action, generating a new current where form ends up being the result of participatory processes determined by economic, sociological, or political parameters. The exhibition’s theme takes shape in this polarized context between the arbitrary formalism of the starsystem and the informal character of the peripheral movements, with the objective of focusing the attention on the core of the profession through the concept of form.

Directed by José Mateus – founder with Nuno Mateus of ARX Arquitetos –, the Lisbon Architecture Triennale took off in 2007 as a platform to promote architectural debate and practice. This 4th edition has two curators: André Tavares, coordinator of Dafne publishers, and Diogo Seixas Lopes, partner with Patrícia Barbas of Barbas Lopes Arquitectos. Sadly, Diogo Seixas Lopes died of cancer in February 2016 and will not be able to see the product of his work, but his figure is present and his concerns resonate throughout the different sections of the Triennale.

The tautological character of the expression ‘The Form of Form’ hampers instant reading, offering instead the opportunity to interpret or go deeper into its possible meanings. It is not a slogan or an umbrella under which to group examples, but rather the title of a research process that sparks a debate inherent to architects: What is the essence of form? What is the process of creating form like? What are the consequences of choosing one form over another? This theoretical statement is consistent with the nature of the Triennale, which gathers not a collection of representative buildings or projects but a series of images, objects, and thoughts organized around an intellectual discourse. The exhibitions are understood as the materialization of a theoretical essay that has gone beyond the two-dimensional character of a book to interact with the physical space of the galleries or the city. In this sense, the catalogue – not the usual exhibition catalogue but rather a compilation of thoughts – is key to understanding the whole.

The first of the three main exhibitions, which shares its name with the Triennale, is set forth as an experiment in which three international architects – the Belgian Kersten Geers (from the studio Office), the American Mark Lee (from Johnston Marklee), and the Portuguese Nuno Brandão Costa – together design the exhibition space. To this end they establish a set of rules in which Brandão, for instance, chooses the main room of a house designed by Office, and Mark Lee is in charge of rebuilding it at full scale. The result of this cadavre exquis is a sequence of decontextualized places (or recontextualized) that visitors can walk through, experiencing the different spatial situations created by each one of these built forms. This abstract enclosure engages in dialogue with a series of images collected by SocksStudio, anachronistically relating a broad range of visual references from Il Campo Marzio dell’Antica Roma by Piranesi, to the plans of Banco Pinto & Sotto Mayor by Álvaro Siza, via the heliographs of León Ferrari or the axonometric drawings of the Diamond House by John Hejduk, and which are displayed here as reproductions on the walls. Everything is standardized by using the same building system: the interior face of the space is clad in white gypsum board, while the exterior surfaces show the cold-formed steel profiles, generating in this way a unique language that questions the concept of individual authorship. Located across from the Tagus, these interlocking volumes echo the industrial character of the EDP factory and strike a contrast with the curved lines of Amanda Levete’s extension of the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (MAAT), inaugurated with great public success also on 5 October to coincide with the opening of the Architecture Triennale.

From the Building to the City

Far from this first site, in the urban oasis of buildings and gardens of the Gulbenkian Foundation, the second exhibition, ‘Building Site’ deals with the process by which form takes shape on site. A series of particular cases, this time illustrated with archive drawings and plans, pose questions regarding the role of architects in the optimization of production methods, the influence of deadlines, and the social implications of a specific design. The exhibition set-up avoids the typical image of disorder on site to highlight the rigor that a project of this kind requires. The documents that once served as work tools are presented here with the care an artwork deserves. And the aesthetic quality of the items displayed merits no less. The exhibition includes noteworthy examples like Cedric Price’s diagrams for McAlpine, François Hennebique’s patent drawings of his concrete system, OMA’s chronograms of the Casa da Música, and the elevations of David Chipperfield’s Neues Museum.

Back on the Tagus shores, the Centro Cultural de Belém hosts the third section of the Triennial: ‘The World in Our Eyes,’ devoted to the urban scale. Under the solid volumes designed by Vittorio Gregotti in 1990, the exhibition seizes the repetitive structure of Garagem Sul and deploys around the columns a series of cylinders that support the projects selected. This generates islands or archipelagos of information around seven thematic fields (the urban fantastic, structures and superstructures, notations of the spontaneous, predominance of geometry, taxonomical indexing, for and against sprawl, and vast geography) that group the different methods used to describe the city. The FIG Projects platform (founded by the Italian Fabrizio Gallanti and the Chilean Francisca Insulza) has been in charge of selecting 35 examples by international architects – including the Spaniard Pedro Pitarch – that explore the relationship between description and design. By means of analytical and graphic tools, these documents bring to light the system of political, social, or economic relations underlying the urban structure, making the invisible visible through the eye of the architect.

Besides these three main exhibitions, which gradually broaden the focus from the essence of form to the analysis of the city passing through the construction phase, a fourth one goes one step further and deals with logistic networks. This time Portugal’s architecture schools, key instruments in the future of the field, are called to analyze the possibilities of a specific site: Sines, a small fishing town that became a huge port complex in the 1960s. Twenty projects were selected through a competition, and their models and plans are delicately displayed in the decadent halls of the old Sinel de Cordes Palace, the Triennale’s venue since 2012. Aside from this student competition, won by a team from the school of Porto, the organization presented the lifetime achievement award to Lacaton Vassal and the début award (for architects under 35) to the Chilean studio Umwelt.

Seven satellite exhibitions and twelve linked projects complement the central discourse and offer visitors the opportunity to discover surprising spaces. A case in point is Palácio Pombal, which houses an installation by Eduardo Souto de Moura; Thalia Theater, showing the video Ruins of the Apocalypse; or the Paços do Concelho gallery, where one can read the petitions made by a number of architects to the Town Hall in the exhibition ‘Letters to the Mayor.’ The dispersal of events, and the ensuing consumption of energy and time, allows in return to explore the city, so the urban tissue of Lisbon becomes a real-life stage in which to contrast the issues raised in the Triennale. Infrastructures like the recently built Vasco de Gama bridge, construction sites by the Tagus, or the touristic success of the Chiado speak of how architecture transforms reality. And behind these processes of change what lasts is the built form that we can synthesize, and relate with other examples in history, reaching, finally, the form of form. This theoretical framework, which was set out in the opening week from 5 to 8 October, will be reassessed in a lecture series to be held between 17 and 19 November, and will stay present until the closing week from 7 to 11 December, resuming the journey after this important halt on the way to reflect on the essence of architecture.