Eurasia versus Atlantica

The crisis in Ukraine arises from Russian’s yearning for a Eurasian empire, sparked by its historical concern about the geopolitical vulnerability of its limits.

Crimea is not critical; Ukraine is. On its territory we shall witness a struggle that will shape the future of Russia and of Europe. After the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991, Russia suffered a catastrophic decade of demographic, economic, and military decline that demoralized its masses and its elites, but Vladimir Putin’s stepping in as president in 2000 began a recovery of self-esteem and international protagonism based as much on the stability granted by an authoritarian regime as on the rise of oil and gas prices.

As pointed out by many geopolitics scholars since the pioneering work of Halford Mackinder, the extraordinary vastness – eleven time zones – of endless plains with no clear natural boundaries to facilitate defense has created in Russia a permanent feeling of insecurity. After its defeat in the Cold War, this insecurity was made more acute by the western interventions in Serbia and Iraq, carried out without fear of Russia nor respect for its interests, intensifying the perception of being besieged that explains Putin’s aggressive policies in defense of its areas of influence, in Georgia in 2008 and right now in Crimea. But in the determination to reconstruct a Eurasian empire, the essential piece continues to be Ukraine, and it is hard to imagine Moscow giving up the cultural and geographic legacy of the Kievan Rus, its cradle in the High Middle Ages.

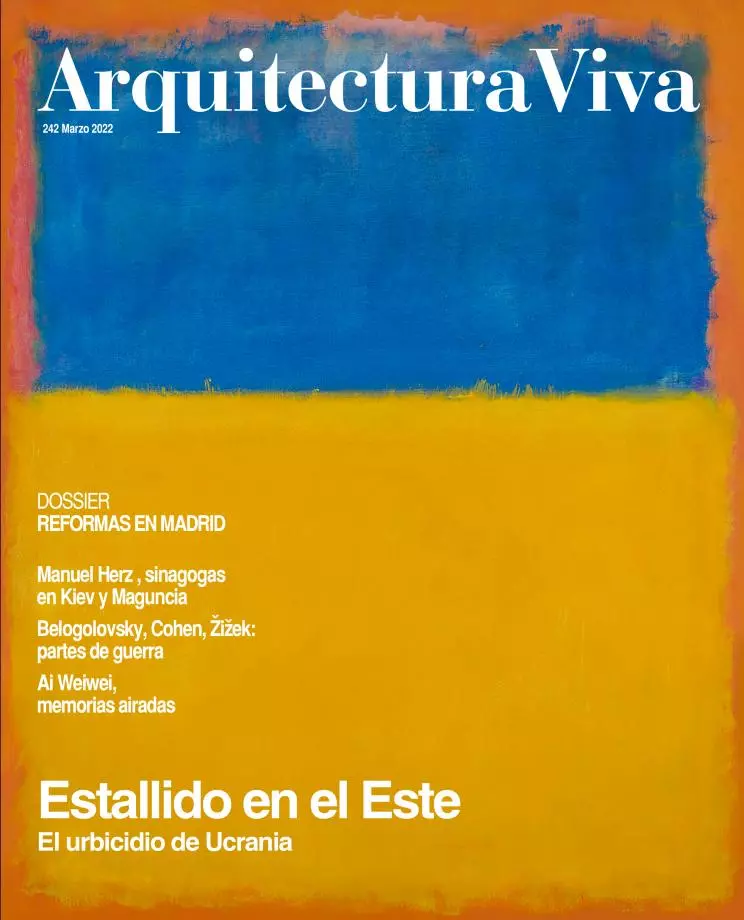

Pro-European demonstrations in kyiv

Geopolitics, which was so influential in the early 20th century, earned a bad reputation through association with the German determination to expand its Lebensraum, but after the fall of the Berlin Wall, it resurfaced as an efficient tool for interpreting world conflicts. Robert Kaplan – who with his 2012 bestseller, The Revenge of Geography, has done so much to popularize the discipline established by Mackinder – has quoted statements made to Rossiyskaya Gazeta by Russian foreign minister Andrey Kozyrev less than a month after the dissolution of the Soviet Union: “ideological confrontation is being replaced by a struggle for spheres of influence in geopolitics.”

Vulnerable as never before in times of peace, Russia has since then sought to ensure its security with a glacis of non-hostile states, an effort indeed made difficult by NATO’s enlargement with ten countries of the old Warsaw Pact. In its first reduced form, the new political and economic alliance will emerge as the Eurasian Union, announced by Putin for 2015, and which will include Belarus and Kazakhstan, but whose geographical profile would seem amputated if Ukraine ended up leaning towards the European Union, following the Association Agreement that sparked the current crisis.

Acutely aware of its geopolitical interests but having no other ideology than Great Russia nationalism – and thus unable to confront western liberal democracy with attractive values on which to base a ‘soft power’ –, Russia has resorted to the confusing amalgam of orthodox traditionalism and revolutionary conservatism so eloquently expressed by the political scientist Alexander Dugin – sometimes dubbed Putin’s Rasputin –, whose thesis on the opposition between the land empire of Eurasia and the sea empire of Atlantica (essentially the United States and Great Britain) has become popular among the country’s political and military elites.

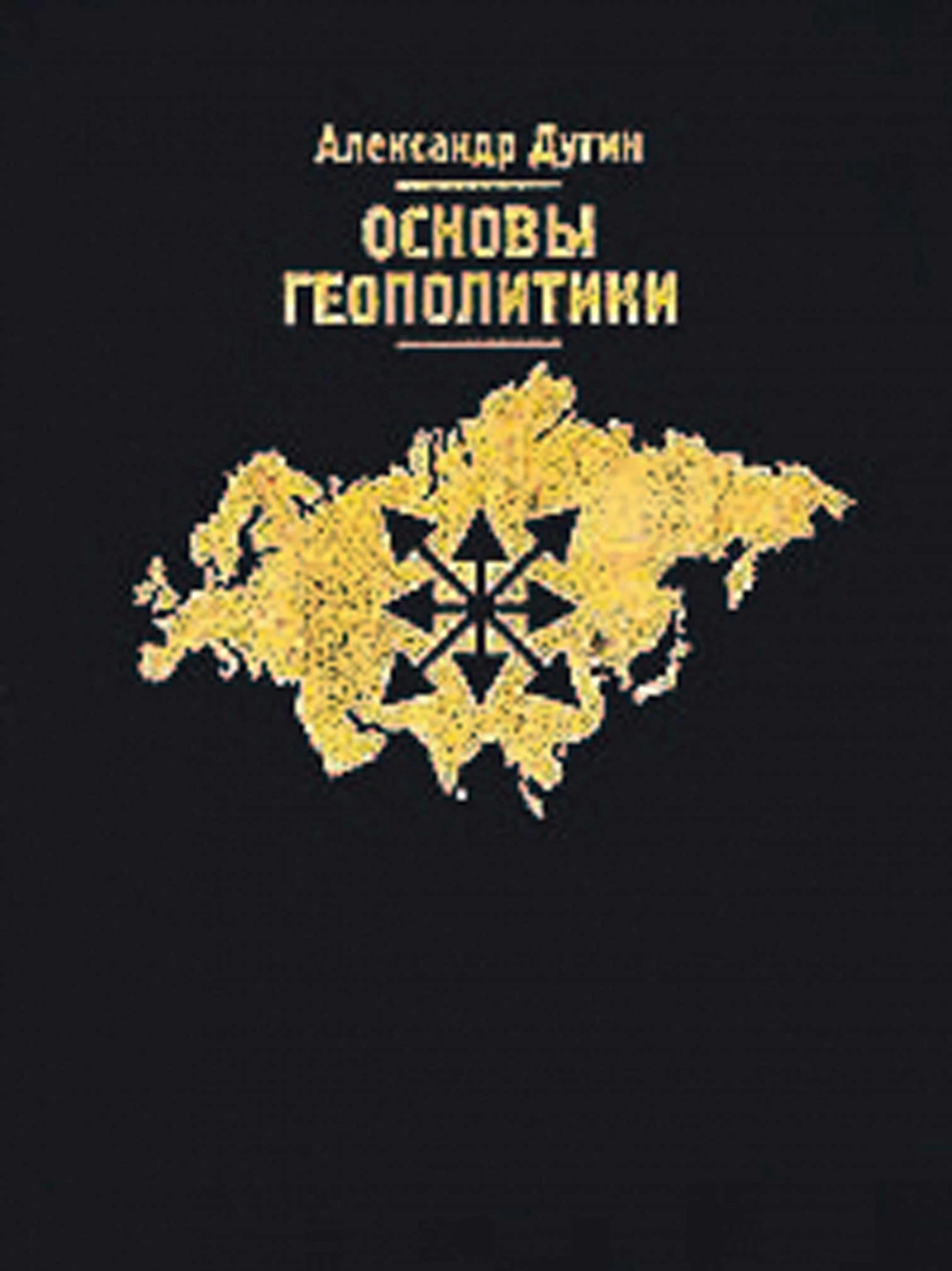

Nourished as much by the traditionalism of René Guénon and Julius Evola as by the totalitarianism of Carl Schmitt and Ernst Jünger or the New Right of Alain de Benoist, Dugin has given new life to the venerable Mackinder’s perception of the Eurasian Heartland as ‘The Geographical Pivot of History,’ in continuity with the also Eurasian doctrine of Prince Nikolai Trubetzkoy and the historian Lev Gumilev; and he has also promoted the Berlin-Moscow-Tehran axis as an essential element of a so-called tellurocracy opposed to American thalassocracy. With his 1997 work The Foundations of Geopolitics: Thinking Spatially the Future of Russia, a textbook in military academies, Dugin moved from lunatic fringe to the political and intellectual mainstream; and needless to say, in his defense of a post-Soviet empire at odds with Atlanticism and liberal values, Ukraine ends up being the keystone of the arch, because without it, the Eurasia he upholds makes little sense.

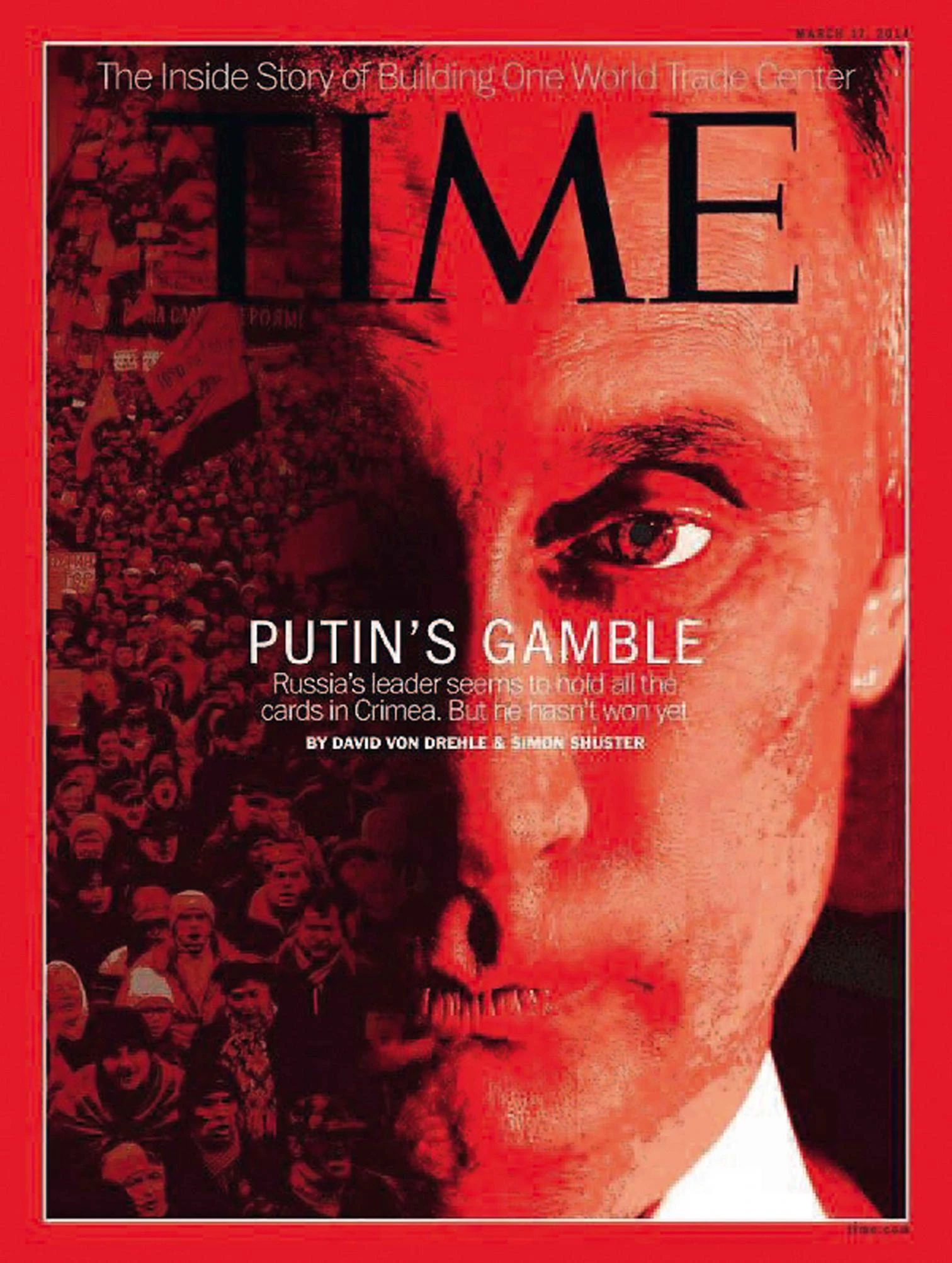

Vladimir Putin’s bold gamble in Ukraine is based on the influence wielded by oil and gas, and also addresses the geopolitical theses of Dugin, which defend the opposition between a land and a sea power.

The European Union, which is reducing its dependence on Russian gas, has fanned the Kiev revolts in a more rhetorical than responsible way, siding with an ambiguous Euromaidan and challenging a Russia that thinks of its interventions in Georgia or Crimea as essentially defensive, a perception that few western analysts share. Alexander Dugin, who while not being exactly the regime’s ideologue has coined its most consistent geostrategic thinking, has recently called the Urkaine crisis a “war of continents,” and we can only hope or wish that this proves false in the weeks and months to come.