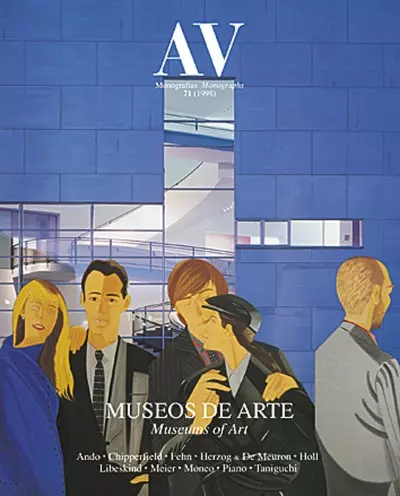

Museums of Art

Museums of Art

Publication information

MUSEOS DE ARTE

Museums of ArtDel gabinete al escenario

From Collection to Stage

Luis Fernández-Galiano

El arte del museo

The Art of the Museum

Luis Fernández-Galiano

Con faldas y a lo loco

Some Like it Hot

Formas consagradas

Consecrated Forms

Kenneth Frampton

La luz es el tema: Museo de Arte Moderno y Arquitectura, Estocolmo

Light is the Theme: Museum of Modern Art and Architecture, Stockholm

Rafael Moneo

Kristian Gullichsen

Un objeto ajeno: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, Helsinki

An Alien Object: Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki

Steven Holl

Marja-Riitta Norri

Paisaje cultural: Centro Aukrust, Alvdal, Noruega

Cultural Landscape: Aukrust Center, Alvdal, Norway

Sverre Fehn

Richard Ingersoll

Un invernadero para el arte: Colección Beyeler, Basilea

A Greenhouse for Art: Beyeler Collection, Basle

Renzo Piano

Martin Filler

La gran montaña de caramelo: Centro Getty, Los Ángeles

The Big Rock Candy Mountain: Getty Center, Los Angeles

Richard Meier

Modelos de crecimiento

Models for Growth

Peter Buchanan

De perfil comedido: Galería Tate de Arte Moderno, Londres

A Restrained Profile: Tate Gallery of Modern Art, London

Jacques Herzog & Pierre de Meuron

David Cohn

Espiral de fractales: ampliación del Museo Victoria & Albert, Londres

A Fractal Spiral: Victoria & Albert Museum Extension, London

Daniel Libeskind

Kaye Geipel

Restituir un torso: reconstrucción del Neues Museum, Berlín

Restoring a Torso: Neues Museum Reconstruction, Berlin

David Chipperfield

Cynthia Davidson

Falsas esperanzas: ampliación del Museo de Arte Moderno, Nueva York

False Hopes: Museum of Modern Art Extension, New York

Yoshio Taniguchi

Stephen Fox

La belleza frágil: Museo de Arte Moderno, Fort Worth

The Fragile Beauty: Modern Art Museum, Fort Worth

Tadao Ando

Luis Fernández-Galiano

The Art of the Museum

THE MUSEUM is a contemporary institution. Before the French Revolution, collecting and looting were at the heart of the accumulation of objects deemed valuable for their beauty or rarity; but these items were not displayed in any regular way in buildings erected for the purpose. The word museum means the place of muses, and the oldest we have knowledge of, the Museion of Alexandria, was a depository of artistic objects intended to make its pensioners receive the muses in the form of inspiration. The ancient world abounded in collections of art works based on acquisition or pillage, and this tradition continued through the Middle Ages with relics of saints or exotic curios brought back by travelers and merchants, adding to the precious metals or gems that came with the spoils of war. The Renaissance penchant for antiquities and the inquisitive spirit of the Baroque Age further induced the amassment of art pieces and natural objects – rocks, shells, fossils – in the 16th and 17th centuries, while the scientific expeditions of the 18th left major collections of botanical and ethnographical discoveries in their wake. Yet the history of the museum proper spans only two centuries, summed up here in ten movements.

From the Collection to the Museum, circa 1800

With the Enlightenment, the magical cult of muses or saints gave way to the veneration of human reason; and with Romanticism, the flaunting of art riches or war trophies evolved into the exhibition of the unique personalities of nations. Science and nationalism transformed collections into museums, and the institutions we know as such began to emerge in the early years of the 19th century, along with their characteristic containers. If up to 1800 the collections had been housed in mansions or palaces, now buildings began to be erected for the express purpose of publicly displaying artistic, historical and scientific objects. Notwithstanding, some of the first museums were accommodated in existing constructions. Thus in 1791 France’s Convention decided to turn the royal palace into a museum, initiating a process which the Louvre would not see the culmination of until two centuries after Napoleon’s inauguration of the Grand Gallery; and Joseph Bonaparte, following the example of his brother, decreed that the Spanish royal collections be placed in the Prado, a building designed by the architect Juan de Villanueva as an Academy of Science and Natural History.

Durand’s Model: Von Klenze and Schinkel The first museum project was a theoretical model published by the French J.N.L. Durand in 1802. Consisting of vaulted galleries surrounding courtyards, a central domed rotunda and colonnades on the facade, Durand’s design inspired many 19th-century architects and not a few of the first half of the 20th. During the last third of the 19th century, for example, Madrid witnessed the construction of the National Library and Museums building; drawn up by Francisco Jareño in 1865, its floor plan still faithfully reproduced the model of Durand. But due to the vast dimensions of this, it more often happened that museums followed it only partially, as was the case of two German buildings of the early 19th century: the Glyptothek in Munich, an 1816 work of Leo von Klenze, applied a quadrant of the original scheme to create four vaulted wings around a square courtyard; and the Altes Museum in Berlin, designed in 1823 by Karl Friedrich Schinkel, used half of the French model, including the domed rotunda and the colonnade, though heightening its monumentality by adding the grand stair that would become a popular feature of museum design.

Soane and Paxton, Gallery and ContainerAlong with the ideal project of Durand, the very real Grand Gallery of the Louvre – converted into a space for artistic recreation and historical pedagogy – had a powerful influence on the imagination of museum architects. In fact, the first building ever to be erected as an actual museum adopted the scheme of the long gallery illuminated from above: the Dulwich Gallery, built outside London by John Soane between 1811 and 1814 to house the collection of a French emigré, was the first of a type that has survived to our days, and initiated the concern for the nuanced use of natural light that has come down to the latest generation of museums. Curiously, the picture gallery also serves as a mausoleum for its founder, and this sanctuary condition taints the innovative spirit of its architecture with an archaic tone that goes back to the mythical origin of museums. Also in London, Joseph Paxton devised in 1850 a large iron and glass structure that represents the opposing pole of the museum debate: the Crystal Palace is a transparent neutral space that has been paradigm for some of the most important museums of the second half of the 20th century.

1850-1950, a Hundred Years of Routine After Paxton, it took a century to resume the impetus of innovation. The eclosion of museums that occurred during the first half of the 19th century would not repeat itself with such fervor until way into the second half of the 20th. The hundred-year interim saw a regular flux of realizations, but neither in quantitative impact nor in qualitative import were they comparable to those of the immediately preceding and succeeding periods. The half-century between 1800 and 1850 produced a wave of innovations that spanned from Durand to Paxton and included Soane, Von Klenze and Schinkel, while 1959, the year of the opening of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim, initiated a new museum boom in which practically all the great architects of the latter half of the 20th century have taken part, from Mies and Kahn to Stirling, Venturi, Moneo, Piano, Meier or Gehry. Common to most of these museums is the importance given to the uniqueness of their architectures, which at times compete in visibility with the collections they house. Over and above their museum functions, many of these buildings aspire to be expressions of their authors’ distinctive languages.

Wright and Mies, the Ramp and the TempleUniqueness is what characterizes the New York headquarters of the Guggenheim Foundation, a huge helical ramp facing Central Park which the American Frank Lloyd Wright finished the year he died. Considered one of his masterpieces and soon counted among the city’s symbols, the building was also much criticized for its poor functionality as a museum. The architectural spectacularity of the large central atrium, toplit and surrounded by the spiral ramp, clashed with the inevitable difficulties involved when displaying paintings in a space of sloping floors and curving walls. Also praised as architecture but censured as a museum was the National Gallery of Berlin, a likewise late work of another great modern master, the German Mies van der Rohe, who achieved with this museum, carried out between 1962 and 1968, his most important building in his native country. The monumentality of the colossal horizontal roof over steel pillars gives the construction a severity that is at once archaic and modern; but the glazed grand foyer is hardly appropriate for exhibitions, and the opaque plinth does not provide the natural light necessary for the optimal display of the collection.

Louis Kahn’s Timeless Works Unlike these extraordinary but controversial projects, the museums of the Estonian-born American Louis Kahn managed to combine architectural excellence with functional efficiency in the museum program. Of the several he built, the last two deserve honorable mention: the Kimbell Museum at Fort Worth, Texas, carried out between 1966 and 1972, is formed by a series of parallel concrete false vaults which create monumental yet intimate spaces, contemporary in their bareness and timeless in their references to classical Roman architecture; while Yale’s British Art Center in New Haven, Connecticut, designed in 1969 and completed in 1974, the year of Kahn’s death, is a sober urban building that gives no hint to the luminous and forceful solemnity of its inner courtyards, around which the well-proportioned galleries are arranged. These two exquisite masterworks were a reference, more admired than imitated, for the authors of the latest generation of museums; although the renewal of the concept and program of the museum would be undertaken by architects more inclined toward Paxton’s containers than toward the forms inherited from the ancient world.

High Technology, from Pompidou to Sainsbury Of the engineering-type museums, the most influential was the Pompidou Center in Paris, an enormous refinery of glass and metal with a structure exposed to view and the large colorful tubes of services or escalators adorning the facades. Situated in the midst of the placid and traditional Marais quarter, this giant machine endeavored to demystify art and make it more accessible, in line with the populist fervor of the intellectual rebellion of ’68. Constructed between 1972 and 1977 by the Genoese Renzo Piano and British Richard Rogers, the building was an instant success, despite the polemic raised, and it remains one of the planet’s most visited spots. Less popular but just as radical in its effort to integrate art with life was the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich, Norfolk, built between 1974 and 1978 by the Norman Foster, a former partner of Rogers; both having been disciples of the American Buckminster Fuller, a most eloquent champion of futuristic technology. Here the monumentalization of technique results in a huge minimalist and abstract hangar inside of which art works blend in with classrooms and workshops, blurring the line between the extraordinary and the everyday.

Stirling and Moneo’s Postmodern Classicism The postmodern reaction – actually premodern in its search for traditional models and antimodern in its disdain for technology – reached the realm of museums as well, led by two masters. Between 1977 and 1984 James Stirling built Stuttgart’s Staatsgalerie, which is arranged around a cylindrical stone courtyard – an ironic reference to the rotunda of Schinkel’s Berlin museum – and decorated with half-buried classical columns and thick motorway rails painted in bright colors. Also classical in its references and modern in its distances is Mérida’s Museum of Roman Art, constructed between 1980 and 1986 by Rafael Moneo; in this case the brick arches are what evoke the Roman past lying amid the visitable foundations, and the industrial catwalks and high skylights the reminders that the spectator has not been transported to a bygone age. Academic and populist, refined and loquacious, both these museums count among the major achievements of their respective authors, and among the cultural works of architecture that have been most unanimously received by the general public, so reticent as it often is when faced with the rough abstraction of the modern avant-gardes.

Culture of Leisure and Thematic Museums In these final years of the 20th century, museums have undergone an extraordinary spurt of growth, associated with the spread of the culture of leisure. Existing institutions have expanded to accommodate the new crowds of visitors, many cities have built museums as symbols of urban identity, and there is now a whole variety of thematic museums dedicated to subjects as diverse as the Jewish Holocaust, recreational science, children, fashion, cartoons or rock. With the enlargement of the Louvre – including I.M. Pei’s famous glass pyramid – and the conversion into a museum of the Quai d’Orsay Station, Paris exemplifies the urban mutations induced by mass tourism; with its eight museums erected during the decade of the eighties, Frankfurt represents the case of cities who have used these institutions as emblems of dynamism and prosperity; and the Jewish Museum of Berlin, completed in 1998 by the Polish Daniel Libeskind, can serve to illustrate the planetary phenomenon of thematic museums, which often succumb to the trivial figuration of amusement parks, but in some cases, like this one, offer the architect the opportunity to experiment with new languages.

Guggenheim, Turn of Century Art and Spectacle Though many institutions of more conventional scope and scale have gone up in past years – such as the Menil Collection by Renzo Piano in Houston, the Kunsthalle by Rem Koolhaas in Rotterdam and the numeous museums of the Viennese Hans Hollein, the American Robert Venturi or the Japanese Arata Isozaki and Tadao Ando – this last phase of museum history has been singularly characterized by the spectacular colossalism of which a good example is the Getty Center, a group of buildings forming an acropolis on a Los Angeles hill, completed in 1997 by the American Richard Meier. Nevertheless, the most emblematic construction of the turn of the millennium is in Spain: Bilbao’s Guggenheim, a huge sculpture of stone and titanium designed by the Californian Frank Gehry, has since its opening in 1997 become the symbol of the city, the paradigm of the spectacle-museum, and the best representation of the relationship between cultural industry and mediatic society. With this building, which wraps up a circle initiated in the foundation’s New York headquarters forty years ago, the trend of singular museums reaches a climax, and perhaps the start of its decline.

index

-

Pages 4 -7

El arte del museo [English too]

Fernández-Galiano, Luis

-

Pages 8 -9

Con faldas y a lo loco [English too]

Fernández-Galiano, Luis

-

Pages 12 -27

La luz es el tema: Museo de Arte Moderno, Estocolmo [English too]

Frampton, Kenneth

Arquitecto: Moneo, Rafael

Proyecto: Museo de Arte Moderno, Estocolmo

Ubicación: Suecia -

Pages 28 -37

Un objeto ajeno: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, Helsinki [English too]

Gullischen, Kristian

Arquitecto: Holl, Steven

Proyecto: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo, Helsinki

Ubicación: Finlandia -

Pages 38 -45

Paisaje cultural: Centro Aukrust, Alvdal, Noruega [English too]

Norri, Marja-Riitta

Arquitecto: Fehn, Sverre

Proyecto: Centro Aukrust, Alvdal

Ubicación: Noruega -

Pages 46 -57

Un invernadero para el arte: Colección Beyeler, Basilea [English too]

Ingersoll, Richard

Arquitecto: Piano, Renzo

Proyecto: Colección Beyeler, Basilea

Ubicación: Suiza -

Pages 58 -75

La gran montaña de caramelo: Centro Getty, Los Ángeles [English too]

Filler, Martin

Arquitecto: Meier, Richard

Proyecto: Centro Getty, Los Ángeles, California

Ubicación: Estados Unidos -

Pages 78 -85

De perfil comedido: Galería Tate de Arte Moderno, Londres [English too]

Buchanan, Peter

Arquitecto: Herzog, Jacques; De Meuron, Pierre

Proyecto: Galería Tate de Arte Moderno, Londres

Ubicación: Reino Unido -

Pages 86 -93

Espiral de fractales: Museo Victoria Albert, Londres [English too]

Cohn, David

Arquitecto: Libeskind, Daniel

Proyecto: Ampliación del Museo Victoria Albert, Londres

Ubicación: Reino Unido -

Pages 94 -103

Restituir un torso: Neues Museum, Berlín [English too]

Geipel, Kaye

Arquitecto: Chipperfield, David

Proyecto: Ampliación del Neues Museum, Berlín

Ubicación: Alemania -

Pages 104 -113

Falsas esperanzas: Museo de Arte Moderno, Nueva York [English too]

Davidson, Cynthia

Arquitecto: Taniguchi, Yoshio

Proyecto: Ampliación del Museo de Arte Moderno, Nueva York

Ubicación: Estados Unidos -

Pages 114 -119

La belleza frágil: Museo de Arte Moderno, Fort Worth [English too]

Fox, Stephen

Arquitecto: Ando, Tadao

Proyecto: Museo de Arte Moderno, Fort Worth, Tejas

Ubicación: Estados Unidos

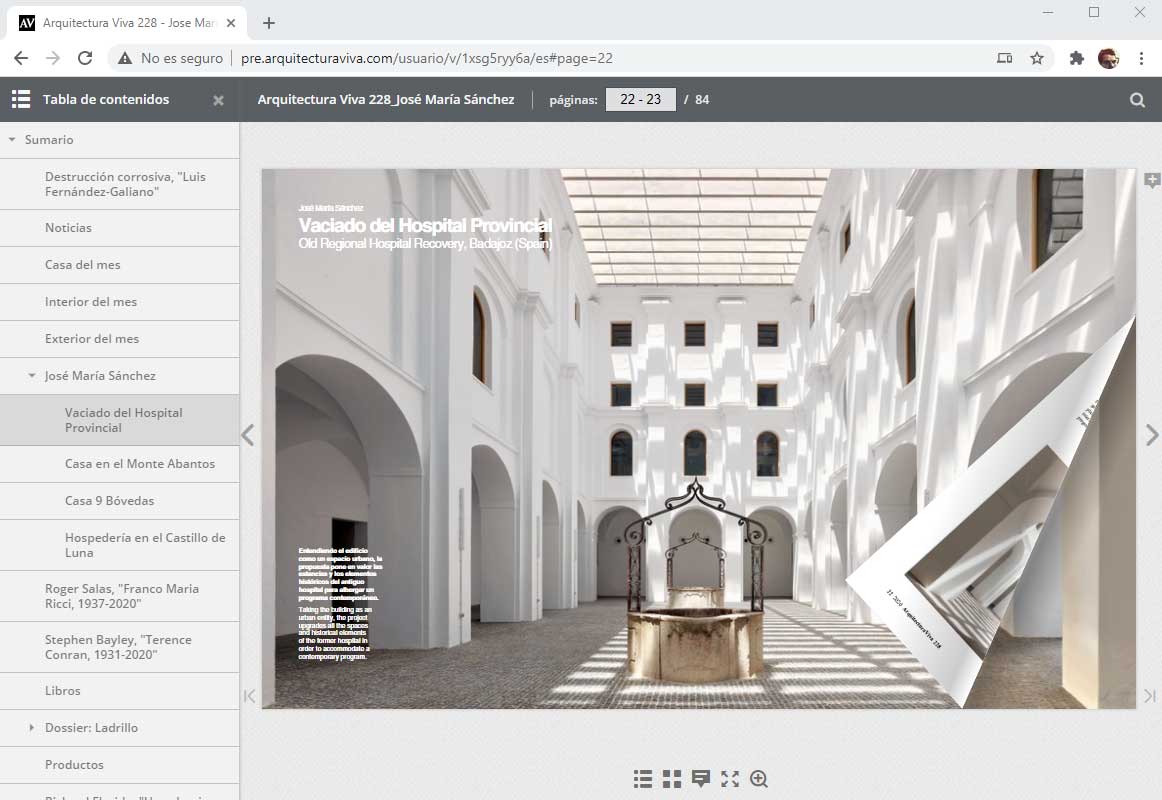

New digital publication viewer

The digital viewer from Arquitectura Viva gives you a new experience browsing our publications in a simpler and agile way in all your devices

Try now