•Austral Chart

•Artificial Gas

•Cinema Constructions

•More Towers and More Walls

•Gravity and Grace

•Two Stadiums, Two Battlefields

•The City is a Tree

•It’s the Economy, Ecologists!

•Spanish Landscapes

•Inconspicuous Mastery

•Motor Works

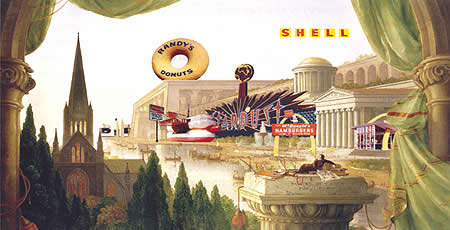

•The Oil of Icons

•Fog in the Desert

•Advent Homily

•Overseas in October

•Totem and Catastrophe

•Asian Luxury

•Piano ‘lontano’

•Philip Johnson, Master of Infidelity

•Sudden Beauty

•What is bothering me?

•The Architect’s Dream

•The Airport and the Village

•Scottish Inquiries

•Venice: Lions and Chimeras

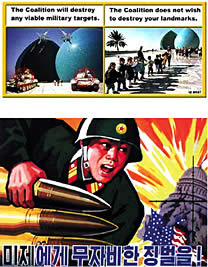

•The Enemy´s House

•Stealth Aesthetic

•The Construction of the Disaster

•Jørn Utzon, Pritzker Prize 2003

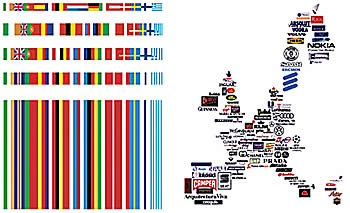

•Asia on one hand, Europe on the other

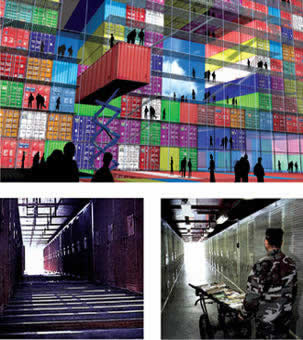

•Construction Games

•Babel vs. Babylon

•Glass Shells

•Dead Seas

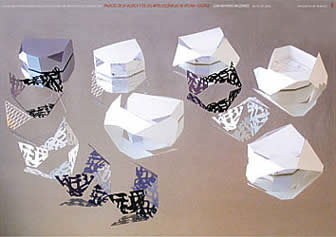

•Navarro Carves the Auditorium of Vitoria in Silver

•Francisco Mangado, on the Outskirts of Ávila

•Eccentric Albion

January 2007

The Celtic Tiger

The spectacular Irish prosperity fuels a real estate growth that is quickly suburbanizing the country, but it also triggers an architectural boom that reflects the lights and the shadows of cultural modernization and economic success. Prominent architects and projects inside and outside the island confirm this. (Photograph: Hisao Suzuki)

Luis Fernández-Galiano

The Celtic Tiger

Ireland rides on the back of a tiger. The sleepy dragon of the Emerald Isle has become a feline as ferocious and flexible as its fellow kind from the Pacific, and the fairy-land of Yeats has turned into an Atlantic athlete that displays its financial muscle assuring that it feels closer to Boston than to Berlin. But this Celtic tiger – as it was called by Morgan Stanley a decade ago – has a heart of shadow; the Irish economic miracle is weaved around a silent and resonant cavity of waste towns and daily endurance. Material progress and cultural modernization have produced destitute margins and faded identities, redundant people and indifferent lives, in an exacerbation of the individualism and the anomy that reflects us all on its concave mirror. Ireland and Spain are two success stories of the European Union, but Ireland is an accelerated Spain, with fewer taxes and less infrastructures, a faster growth and more immigration; its present is perhaps our future, and this hypothetical circumstance prompts an admiring and warning gaze.

At the last Venice Architecture Biennial, that which takes pride on being the most globalized economy of the planet explored the territorial scenarios for the coming years, after having experienced a spectacular process of urban growth during the last decade. The driving forces behind Irish development are high-technology manufacture and a sophisticated service sector – the country is one of the leading software exporters –, backed by a broad education, the English language and a reduced business tax that have favored the establishment of multinational companies and boosted productivity, which has grown four times as fast as the average of the Union. But the economic impulse is also due to the real estate boom that colonizes the landscapes of the island with a unanimous extension of single-family homes, a colossal dispersion of dwellings that makes the trips to work endless, organizes life around the car – in the absence of efficient collective transport – and increases the country's energy dependence: a series of dysfunctions that the curators of the Venetian exhibition proposed to remedy with a transition from the ‘SubUrban' to the ‘SuperRural', a fortunate motto which replaces the degeneration of the city with the regeneration of nature.

While Ireland reinvents its urban future, its current architecture shows signs of the present fracture and of the growing physical and emotional gap between those who have been able to get on the fast track of globalization and those forgotten in an abandoned station where no trains stop. The work of two couples, who are also associates, can serve as a guide in this excursion of extremes: that of the Irish Róisín Heneghan and the New Yorker of Chinese origin Shi-Fu Peng, both graduated in the late eighties and trained at the Princeton studio of Michael Graves, illustrates the most cosmopolitan dimension of contemporary Ireland; for its part, the latest project of Sheila O’Donnell and John Tuomey, whom after graduating in Dublin in 1976 completed their training at the London office of James Stirling, offers a pedagogical account of the social margins of an incandescent country.

Heneghan Peng have just finished a civic center of diagonal glass and swift edges that goes up in the almost rural Kildare County with the confident presence of a metropolitan visitor, but this new work does not distract them from their main undertaking: the Grand Egyptian Museum in Cairo, a colossal structure close to the pyramids – raised in part with Japanese soft credits – that they won in competition three years ago, and are now carrying out as leaders of a team with engineers in London – the group of Cecil Balmond at Ove Arup – and landscape designers in Rotterdam – the West 8 of Adrian Geuze. From their large and luminous Dublin office, the couple builds exquisite laser-cut models, designs meticulous details and practices American organization methods with their European collaborators in this African project financed by Asians.

Far from the city center, O’Donnell and Tuomey arrive at their studio by bicycle and proudly show the recently released monograph on their oeuvre, with the Glucksman Gallery of Cork on cover, a small work selected in one of the last editions of the Stirling Prize. The book does not include their most recent completion, the Cherry Orchard School, whose bucolic name conceals the dramatic reality of a neighborhood devastated by delinquency and drugs, inhabited by defeated adults and children that wander about the streets, abandoned by broken families and an indifferent society. Started by a visionary priest, the school wants to be a foster home for these children, training them in domestic skills that were not taught to them at home – from hygiene to cooking –, but even this generous undertaking has cautionary chronological and material limits: it only accepts very young kids, because those over ten are considered hopeless; and the school, in any case, has been built to resist vandalism, with solid walls and concrete vaults without roof tiles or sheets that could be pulled off. Only one budgetary exception were the architects able to extract from the education authorities: the walls that separate the school from the surrounding urban jungle would not be made of concrete blocks, as those of the nearby prison, but of brick, to prevent the children from associating both institutions.

Dublin is a literary city, and visitors following the steps of Leopold Bloom or Stephan Dedalus – as those who go to St Patrick’s cathedral in search of Jonathan Swift, or to Trinity College in tribute to Oscar Wilde and Samuel Beckett – are unlikely to get lost in these menacing and desolate quarters. However, the city of Joyce is also that of Bacon, and the reconstruction of the painter’s London studio in the interior of High Lane Gallery – the city museum of contemporary art – offers a visual metaphor of the shreds of darkness that stripe the splendor of the Celtic tiger: in the half-light, surrounded by the sad flesh of some canvasses and the promises of solar happiness of his dictionaries, grammars and textbooks of Spanish, Italian and Greek, the abyssal and abject chaos of the studio offers itself to the gaze behind a glass of urn and sepulcher. Francis Bacon, who died in Madrid in our annus mirabilis of 1992, was incinerated without witnesses in the cemetery of La Almudena, but his true remains lie in the desperate confusion of this den of papers and paint. The Ireland of the diaspora, that was once ember, returns as dust to the fertile womb of the mythical nation, asleep yesterday and today sleepless rider of an animal of ashes and gold.

November 2006

Austral Chart

Chile is having a heyday economically and politically and part of this is the extraordinary quality of its latest architecture, currently the most interesting in Latin America. The Biennial recently held in Santiago displayed the country’s most outstanding projects and, with a numerous Spanish contingent participating, debated on the state of architecture in the world. (Photograph: Cristóbal Palma)

Luis Fernández-Galiano

Austral Chart

Chile is having days of wine and roses. Neither the regular Mapuche protests nor the cases of corruption that have tainted the Concertación government, nor the judicial vicissitudes of a dictator lost in his own labyrinth of solitude have managed to alter the overwhelming self-esteem reflected in the Bicentennial Poll, conducted in preparation for the 2010 celebration and recently disseminated by El Mercurio. Three out of every four Chileans consider their homeland “the best country in Latin America to live in,” according to the poll published by the Santiago daily. Spain too, incidentally, stands out in the survey results as the most admired, ahead of the United States, a perception that accompanies the substantial Spanish presence in key sectors of Chile’s economy: Endesa controls 50% of electricity generation, Movistar supplies 47% of mobile phones, Santander and BBVA jointly cover 30% of banking, Agbar has 35% of its sector’s clients through Aguas Andinas, and firms like Sacyr, Cintra, OHL and ACS are leaders as builders of infrastructures ranging from airports to motorways; figures which elsewhere in Latin America would arouse more resentment than appreciation.

In this case, the admiration is to a large extent mutual, and the diagnosis published in El País in April by Alain Touraine, “Chile as a Model,” is shared by most of the political and corporate leaders in Spain, where both Michelle Bachelet and her mentor Ricardo Lagos are praised for their determination to make economic growth and social justice compatible, as well as for their lucid ability to combine remembrance of the victims of the dictatorship with the quest for consensus and national reconciliation. This latter objective is symbolically materialized in the Palacio de la Moneda , the grand classicist Baroque building whose construction by Joaquín Toesca in the 17th century is portrayed in Jorge Edwards' novel El sueño de la historia, and the bombing of which on 11 September 1973 became the tragic emblem of General Augusto Pinochet's coup d'etat against Salvador Allende's government. It is the presidential residence that Lagos decided to clear of demons through a large cultural center buried at its feet, underneath the ceremonial palace square: a colossal volume lit naturally from above and flanked by ramps, designed by architect Cristián Undurraga, which represented the country in the last Biennale di Venezia and which itself was the venue for the exhibition and conferences of Chile 's own Bienal de Arquitectura.

The selection of projects for the exhibition makes a plausible portrait of the here and now of Chilean society, whose economic boom is thanks to private initiative taking the lead, leaving little room for state participation, so unlike the way things work in many European countries, where architecture that stands out in any way is mostly commissioned by public clients. Projects of this nature are rare in Chile. Works as formidable as the Elemental social housing development in Iquique, spearheaded by Alejandro Aravena, or as polished as the public services building in Concepción, designed by Smiljan Radic, are exceptions to the rule. The bulk of the exhibition shows houses built for affluent clients – among these the extraordinary Casa Poli, a neo-plastic prism designed by the young team of Mauricio Pezo and Sofía von Ellrichshausen on a vertiginous cliff over the Pacific – besides private universities like Mathias Klotz’s Diego Portales or José Cruz’s Adolfo Ibáñez, corporate headquarters, the inevitable winery, and the no less inevitable exotic hotel, in this case Germán del Sol’s very appropriately named Remota.

With a rich Spanish representation, culminating with Rafael Moneo's stellar appearance on closing day, the series of lectures and debates organized by the Bienal revealed both how proud Chileans are of their own achievements and how cosmopolitan they are in their curiosity about what goes up abroad, making for a professional panorama whose intellectual and aesthetic proximity to Europe or the United States contrasts with its geographic distance from both. Neruda's mythical Chile continues to exist in the country's vast territory and in the moving devotion of those who pilgrim to his house in Isla Negra – where he is buried in the garden, facing the ocean and close to his devotional figureheads – like one visiting a national and poetic sanctuary. But the topographic and dilapidated beauty of Valparaíso is now undergoing refurbishment with the money of Chile 's new prosperity, the profits from its mines are being complemented by the vegetal splendor of exportable crops, and the warm valleys at the foot of the mountain range are filled with vineyards of impeccable geometry. There, the rows of vines are finished off with rosebushes to facilitate early detection of plagues, and perhaps this unexpected meeting of wine and roses is a good metaphor for the aromatic and euphoric moment that the austral country is enjoying. Collige , Chile , rosas.

October 2006

Artificial Gas

The Gas Natural building in Barcelona is not just a company headquarters. Conceived by the late Enric Miralles, its suspended, shaken volumes express the changing confusion of the times. Rising in the silhouette of the Catalan capital like a citizens’ landmark, it is an emblem of the artistic avant-garde and a sign of economic power. (Photograph: Iñigo Bujedo)

Luis Fernández-Galiano

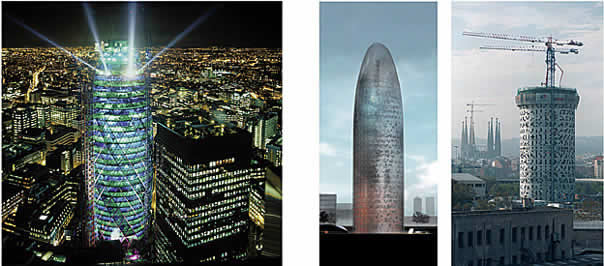

Artificial Gas

Rather dead than plain: the headquarters of Gas Natural is a provocatively affected work, what with its random interlockings, implausible projections, and decomposed volumes. Everything about it is forced and excessive, with that mood of irresponsibility that characterizes a cartoon and the playful origami that comes to a peak in an inane corbel molded with folds of glass. The sculptural lyricism of Enric Miralles, who in other posthumous works like the Scottish Parliament or the Santa Caterina market has produced amazing fruits, becomes sadly arbitrary here, while the calligraphic violence of his drawings seems to be domesticated by the conventional vulgarity of a curtain wall that is barely nuanced by variable fragmentation and random coloring. The building turns out to be an accidental headquarters because its true function is to be an urban landmark, raising its teetering forms over the broad landscape of the Barceloneta quarter, while expressing the transition from the old gas plant's material and structural clarity to the immaterial and mediatic argument of our own postindustrial times.

The prematurely deceased Catalan architect left a handful of remarkable works – which are all the more brilliant when most topographical – because his bright choreographies required making dance steps on a territory shaken by the forces of context, and this is perhaps why many judge the dreamlike orography of the Igualada cemetery, where he is buried, as the project where his language of gestures comes forth most eloquently and movingly. In the Barceloneta, however, the effort to bring together adjoining urban tensions in a sculptural piece that crystallizes fluxes with its quiet movement is contradicted first by its vertical formation, which does not manage to connect with the lower volumes in a coherent whole but rather makes the cantilevers mere athletic anecdotes, and second by its vitreous lightness, which abstracts the building from the solidness of ground without which the gymnastic gravitas of Miralles's finest moments cannot easily come true. Enric may have had his head in the clouds, but his architecture was great as long as he had his feet firm on the ground.

It is probable that in the same way that Barça is more than a soccer club, Gas Natural is more than an energy company. After all, it is one of the Caixa's industrial jewels, formed by the merger of Catalana de Gas and Gas Madrid , and surely this symbolic circumstance had something to do with the decision to build a unique headquarters, one where corporate needs are subordinated to artistic expression and its role as urban landmark. But we have to resist the temptation to associate Miralles's dynamic, unstable aesthetic to a Catalanism that would quickly have moved from the seny to the rauxa, as so many recent episodes of the once-upon-a-time ‘oasis' suggests, from the ill-fated Gas Natural takeover bid on Endesa to the most absurd vicissitudes of Maragall's tripartite government, from the stunned trip to meet with ETA in France to the soul-searching drafting of the Statute, and through the climate of political intimidation and street violence that has prevailed of late, presenting a distorted image of Catalonia. The disconcerting volumes of Gas Natural should not be the emblem of these troubled times, because the touch of surreal madness that characterizes this land must end up being absorbed by its civil culture of pacts and good sense. Of course the strident polarization of Madrid's politicians and journalists does not help to alleviate the stormy atmosphere of a Catalan scenario that has slid from its famous calm to the urban guerrilla of okupas that forces to cancel a summit meeting of European ministers or the torch parades that are more evocative of the totalitarian aesthetics of the 1930s than they are of the country's Gothic roots. But Catalonia (and the Caixa that proudly displays its economic muscle with the Gas Natural building) has more to win with a ‘soft power' in the Joseph Nye manner, woven with seduction, emulation, and example, than with abrasive confrontations reminiscent of the long gone social panorama of a bomb-ridden Barcelona once known as rosa de fuego.

Exactly a year ago, during the fishermen's blockade of the main Mediterranean ports, the front page of El País showed a picture of Barcelona as seen from the sea. By doing this it inadvertently threw light on the new landmarks of the city's profile, which turned out to be the corporate headquarters of two companies controlled by the Caixa, a savings bank that thereby affirms its central position in Catalonia 's social landscape. Both the Agbar shell and the Gas Natural sculptural tower rise over the low profile of the common city as assertive banners: emblems of economic power that do not even turn out to be too costly on the balance sheets of their owners. As the management of one of the Ibex companies disdainfully told the architect of its colossal Madrid headquarters: “In the end, the cost of the building is one billing day.”

The opening of the headquarters of a strategic energy firm ought to serve as pretext to think about the policy of national champions (Spain's or Catalonia's?), to discuss in detail the recent entry of construction companies in the sector of utilities (who knows if it is to prepare for the bursting of the real estate bubble by linking up with more stable enterprises, or to prevent foreign firms from coming into the picture), and to warn the public about the risks behind our growing dependence on imported energy (aggravated by the absence of a common European policy and inscribed within the menacing context of climate change). But our tribal conflicts prevent us from separating the urgent from the truly important, and a building that ought to be a model of energy saving and an example of civic responsibility, with the austere laconism that should be the mark of a company that must guarantee supply without being abusive in its prices, ends up being discussed as the failed artistic icon of an electoral and gaseous Catalonia. Mea culpa.

October 2006

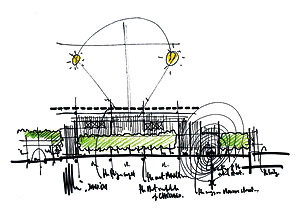

Cinema Constructions

Frank Gehry and Norman Foster are the stars of recent documentaries that portray the architectural profession from opposite angles. Sydney Pollack presents the Californian as an inimitable artistic genius, while Mirjam von Arx describes the Brit’s skyscraper in London’s City as a collective work. (Photograph: Nigel Young/ Thomas Mayer)

Luis Fernández-Galiano

Cinema Constructions

Architecture loves cinema, but rarely is this love reciprocated. Though the moving eye of the camera has often fed on contemporary buildings, cinema has seldom sought to unravel the mechanisms of the creation of spaces, preferring as it does to stick to the use of architecture as a setting and the occasional stardom of cartoonish architects. Three years ago, Nathaniel Kahn's film about the legendary Louis Kahn, titled My Architect: A Son's Journey, was a moving account of an illegitimate offspring's voyage to his biographical origins and to the very heart of architecture, a self-contemplating, bitter and perplexing portrayal of the father he hardly got to know and the master whose footprints he looked for in impassible buildings. It was also tangible proof of the poetry and emotion with which cinema can begin to pay its debt to the world of construction. This last season, Sydney Pollack's documentary about Frank Gehry and Mirjam von Arx's about Norman Foster's London ‘gherkin', premiered almost simultaneously, offer openly opposed views of the social, artistic, and urban role of architecture, and of the processes of professional collaboration, economic negotiation, and political strife that surround it.

In Sketches of Frank Gehry the Hollywood director delineates his architect friend with the hyperbolic strokes of the genius, and as much in relaxed conversations as in numerous interviews with corporate clients and artist colleagues, the veteran master of Los Angeles comes across as a smart playful child who creates beauty with distracted spontaneity, however much his alleged need to suffer because “it is wrong when too easy.” But the film director refutes Gehry's words by filming him in the act of drawing his lyrical tangles of lines with astonishing ease, or building small models with cardboard and tape, pensive at times but jubilant for the most part. Then the architect expresses his admiration for painters and claims he has never managed to achieve “painterly surfaces,” a gesture of modesty that Pollack counters with a fascinating succession of iridescent and undulating facades. In the end, the model is good “when stupid looking.” “What is the material?” “I do not know yet.” In any case, “buildings take so long that by the time they're finished I don't like them.”

From Disney's Michael Eisner to Vitra's Rolf Fehlbaum to the Guggenheim's Thomas Krens or Dennis Hopper who lives in a house designed by Gehry, all his clients come together in a polyphonic litany of admiration. The artists, from Ed Ruscha or Chuck Arnoldi to the ubiquitous Julian Schnabel, join the chorus of praises, and the few architects interviewed, from an already very weakened Philip Johnson to the critics Charles Jencks and Herbert Muschamp, voice opinions of applause or enthusiasm. Only the historian Hal Foster puts a note of censure, but it is so confusedly expressed that it only serves to legitimize the complacent tone of the overall portrait. In this ocean of flattery, the most picturesque figure is Milton Wexler, Gehry's psychoanalyst of the past 35 years, who denies responsibility for the architect's creative transformation (it was after beginning therapy that Gehry gave up the conventional architecture he had been building) and explains how he discourages many an architect who comes to him in search of a miraculous recipe after hearing of his method.

With an approach almost diametrically opposed to the Californian exaltation of individual inspiration, Building the Gherkin presents the building of the London skyscraper as a collective endeavor, and with admirable plausibility the young Swiss director Mirjam von Arx manages to convey both the complexity of the political and media scenes that surround architecture and the diversity of its technical and corporate protagonists. Combining the emotive spectacle of high-rise construction with a narration of the labyrinthine ups and downs of planning and the inevitable conflicts and crises unfolding in the course of development, the documentary is at once an epic and a comedy of manners. As such, it is as pedagogical in its account of the execution and decision-making processes as it is perceptive in its portrayal of the people involved. This is a long cast of managers, bureaucrats, designers, and building contractors: from Norman Foster himself, who argues with frozen laconic accuracy, to the almost sinister municipal urban planning chief, Peter Wynne Rees, passing through the representatives of the client, the insurance firm Swiss Re, who are led by a formidable, intimidating, warm-blooded Sara Fox. All are portrayed with empathy and humor in the documentary, where their indecisions, phobias, and disagreements together make up a vital and vibrant soap opera.

The skyscraper rises on the site of the Baltic Exchange, a building blown up by the IRA. Construction had begun when the attacks of September 11 happened, so the film addresses the impact of terrorism on both the safety of high-rise buildings and the balance sheet of the insurance company behind the tower. These dark shadows are balanced with episodes of high comedy, such as those documenting the decision to assign the interior decoration to another firm, to Foster's huge dismay. The result of four years of work, the documentary about the first skyscraper to go up in the City in twenty-five years – which started out as a controversial project and ended up becoming a symbol of London, appearing in movies like Basic Instinct II and Woody Allen's Match Point – is above all a detailed description of how architecture gets entangled with life itself, and a lucid and critical tribute to the men and women who make possible the miracle of turning sketched dreams into real space. In this implausible territory, Foster and Gehry are not far apart. The recently completed pyramid of the Brit in Kazakhstan seems as oneiric as the dizzying, ethylic forms of the Californian in Álava's Rioja region. In the end all we have are shadows, cinema constructions, dreams of reason or incubi of reason in slumber.

September 2006

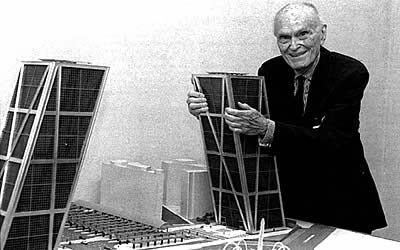

More Towers and More Walls

The continuous increase of the oil price – triggered by the multiplication of demand rather than by occasional supply crises – opens a historic period of energy shortage that shall stimulate saving and the use of alternative sources, inviting new reflections in the fields of sustainable architecture and urbanism. (Photograph: Chad Ehlers/Alamy)

(Photograph: Calatrava´s Studio)

Luis Fernández-Galiano

More Towers and More Walls

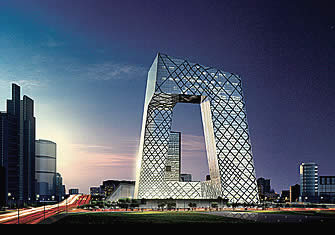

The 20th century ended in Berlin , but the 21st began in New York . The cold war between ideologies came to a close with the coming down of the wall, and the hot war between civilizations broke out with the collapsing of the two towers. Five years after 9-11, the prediction concerning the death of the skyscraper has proven as erroneous as the previous one about the disappearance of the walls that divide the planet. Technical and symbolic globalization continues to raise high-rises that send out an overbearing and optimistic message, while at ground level the world crackles with innumerable boundary fences and computer fire walls that try to block the passage of persons and ideas. (Photograph: AP/Radial Press)

For Chicago , the cradle of skyscrapers, Santiago Calatrava is designing what will be the tallest in the United States , while the federal administration seals the Mexican border with wire fences, pits, and heat sensors. In Shanghai , where cranes and towers abound like nowhere, the completion of the World Financial Center by the American firm Kohn Pedersen Fox will give the city the height record heretofore held by Kuala Lumpur and Taipei , while the Chinese government censors Google and Yahoo and blocks access to the Wikipedia with cybernetic barriers. And in Dubai , in the troubled Middle East that gave birth to the world's first cities, the Chicago office of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill plans to beat Shanghai with an even taller skyscraper, shifting the planet's ceiling to the Persian Gulf , without such an achievement of the global economy preventing boundary walls between rich and poor from going up in the region, whether between Saudi Arabia and Yemen or between Israel and Palestine . Not even in Spain's periphery is the proliferation of towers in the big cities and tourist havens – from Nouvel's polychromatic shell in Barcelona to the four skyscrapers rising on Madrid's Paseo de la Castellana , passing through the many building developments going on along the Mediterranean coast and the Canarian archipelago – incompatible with the closing up of southern frontiers through radars in the Strait of Gibraltar, fences around Ceuta and Melilla, and patrol boats in the Atlantic Ocean, all under siege by the misery of Africa.

Berlin was not the last wall, nor did the attacks against the World Trade Center Twin Towers bring about the end of skyscrapers. In the wake of 9-11, it seemed that skyscrapers were giants with feet of mud, but maybe their vulnerability was not so much technical as social, and the safety of these emblems of political and economic power is more threatened by the multiplication of barriers that fracture the territory, segregate populations, and nourish resentment than by the risks associated with their structural daring and complexity. The suicide cells of September 11 were under the command of Mohamed Atta, who had gone to the Arab world's oldest architecture school, in Cairo (as had Hassan Fathy, Egypt's leading architect, an advocate of neo-vernacular construction at the service of the poor, against western modernity), and gone on to earn a degree in urban planning from Hamburg's TUHH – a young polytechnic university whose dean of urban planning, Dittmar Machule, a defender of traditional schemes, had taken part in refurbishing the ancient Syrian city of Aleppo – with a thesis on the conflict between Islamic town planning and modernity. This makes one wonder if the objective of the terrorist attack may have been not only political, but also architectural. A similar conclusion can be extracted from Eyal Weizman's analysis of the politician Ariel Sharon as an architect, when the writer explores the geometry of the occupation of the West Bank from the viewpoint of the intersection of power, security, and urbanism, showing to what extent military strategy, the geopolitics of protection, and the architecture of territories are inseparable.

Five years after 9-11, the catastrophic clash of the skyscraper and the airplane has rendered high-rise construction more costly, and commercial aviation more troublesome. But the expansive wave of the event has done more harm on the ground than on the sky, and the chain of Islamist bombs that has opened cracks of panic from Madrid to Bali has shaken the architecture of globalization less than the discredit that a bellicose empire has brought upon itself. This empire has proven itself as impotent in guaranteeing security and establishing democracy in Muslim countries as it has shown itself incapable of filling the tragic void of Ground Zero – bogged down as it is in a marasmus that is more real estate-related than civic – with an architectural sign of confidence and hope. On the other side of the Atlantic, London was able to replace the Baltic Exchange, a building destroyed by the IRA, with a light and luminous tower, designed and built by Norman Foster for the insurance firm Swiss Re, that soars above the skyline of the City like a peaceful projectile: if the West wants to propose an icon of encounter and healing for the trauma of horror, this at once swift and blunt skyscraper would be a good candidate indeed.

Meanwhile we will continue to look upon the devastation of Lebanon as a titanic but poor imitation of the deconstructions of Gordon Matta-Clark, the civil war of Iraq as a conflict existing only on screens impassively broadcasting the umpteenth explosion, and Iran's threatening determination to create an Islamic atomic bomb as a mere diplomatic game, all in the course of this uncanny August that has seen Spaniards sequestered by the cruel summer of 1936, Germans from Günter Grass to Arno Breker sequestered by their ominous past, and Cubans sequestered by a Fidel Castro who pathetically sequesters himself, clutching a newspaper as proof of life. But maybe T.S. Eliot was right, and the world ends not with a bang but a whimper: not with an explosion, but with a moan.

July 2006

Gravity and Grace

Early in June, Valencia had a bout of agony and ecstasy. The final regatta prior to the America’s Cup of 2007, which served to open the emblematic building of the marina, the tragic underground railway accident, its casualty list the worst ever in Spain, and the Pope’s appearance on the occasion of the World Family Encounter, together turned the Mediterranean city into a capital of spectacle, grief and piety. (Photograph: David Chipperfield Architects)

Luis Fernández-Galiano

Gravity and Grace

Valencia lived a summer of ups and downs: from the winds on the sails to the victims in the trains, and from there to the visit from the Vatican . In a matter of days it moved from the euphoria of nautical triumphs to the sense of total defeat caused by the railway ordeal, to then seek volatile consolation in the pastoral voice of a philosophical pope. In the first weekend of July, twelve boats from five continents took part in the world's oldest competition, for which Valencia had won the bid to be a venue against nearly a hundred other candidate cities. The final regatta prior to the America 's Cup of 2007 served as occasion for the opening of the Foredeck, a lookout-building designed and built in just eleven months by David Chipperfield and b720/ Fermín Vázquez as center and symbol of the event. The following Monday, the underground station Jesús was the scene of the worst accident ever to happen in a Spanish metropolitan railway. Its over forty deaths switched the city's mood into one of mourning, and not even the mass fervor of the pope's visit the following weekend managed to dissipate the grief of so many desolate families.

From 1934 to her death in 1943, the French mystic writer Simone Weil wrote a diary that was published posthumously, in fragments, under the title Gravity and Grace: two words that expressed the opposition of the heaviness of the world and the lightness of the spirit, but which also perfectly sum up the contrast between the solemnity of death that strikes as collective tragedy and the frivolity of the media event, be it sport-related or religious, that congregates masses around a spectacle or a message. Valencia shifted its attention from the immaterial hustle and bustle of breezes and boats viewed from a lookout, to the somber drama of human catastrophe in an underground labyrinth, closing the circle with the ephemeral architectures and winged words of a pious crowd that chose the aerial forms of Santiago Calatrava for backdrop. Gravity and grace are terms that express the changing mood of the city as much as they suit the contradictory nature of the America 's Cup building whose launching party started this week of passions.

To design and build the Foredeck, also called Veles e Vents as a tribute to a poem by Ausiàs March, Chipperfield and b720 won over competitors like Jean Nouvel, Von Gerkan & Marg, Carlos Ferrater, or Alejandro Zaera. The building is formed by four large platforms that rise with sculptural confidence at the end of the dock, extended along the new canal with a parking lot for 800 vehicles and a garden walk that links this landmark to the seafront and the Malvarrosa beach. “The beach of Sorolla and Blasco Ibáñez,” says Mayor Rita Barberá as we lunch in Las Arenas, a big new hotel built in classicist style that is a counterpoint of opulence to the pure geometries of the Foredeck. Here, the gravitas of Chipperfield's work dissolves in the Mediterranean light of the huge cantilevers, clad in a white-enameled steel that makes them look weightless – an impression reinforced by the transparency of the building's main volume and the almost imperceptible glass parapet of its perimeter.

The spacious shaded terraces – the two lower levels for public use, the two upper ones reserved for guests of the organization – are of course the essence of the project. It is there that the main activities of the building happen: receiving visitors and watching regattas by day, parties of sponsors and gatherings of crews by night. Each of the twelve teams participating in the event has its own base in the port – provisional structures several floors high containing workshops, gyms, dining rooms, offices, shops, and reception areas for guests and the press, outstanding among which is the one Renzo Piano built for Luna Rossa, the Italian ship sponsored by the firm Prada, with its intelligent cladding of recycled sails and a large boutique on the top floor that one gets to by escalator. But only the Foredeck brings everyone together on neutral ground, and it does so with an ease and elegance that makes it hard to imagine any other project on the spot. The deadlines for design and execution were so tight (due to the delays caused by the change of government in Madrid and the attendant political contest for the control of the event) that the work has small imperfections in the details and finishes that mortify Chipperfield. Responding to the congratulations of Public Works Minister Magdalena Álvarez – dressed in sailor outfit to watch the regatta from the sea – the British architect is more keen on stressing what is still lacking than on patting himself on the back for what has already been done.

This attitude is typical of an architect who is stubborn and demanding when it comes to the material quality of his buildings, and who is obsessively self-critical about his work in general. Nevertheless, Valencia's Foredeck is proof, precisely, of the force of architectural ideas, the resilience of concept against haste or misunderstandings, because the initial proposal of the slabs in levitation, with terraces in shade and luminous edges that define an abstract geometric sculpture, so persuasively reconciles the functional needs of the lookout with the sculptural needs of the landmark that no small defect or error can damage the result. The building's lightness is perhaps – as Weil would have had it – that of ideas in strife with matter, but it may also be that which suits a fleeting world, incompatible with the gravity of timeless certainties, a liquid circumstance that upsets Joseph Ratzinger as much as it did his fellow-German Karl Marx, who a century and a half ago described the experience of modernity in The Communist Manifesto: “all that is solid melts into air.” In this Valencian summer of gravity and grace, the weightless ‘sails and winds' building reflects the enterprising mood and hopeful dynamism of the town better than the rhetoric colossalism of the City of the Arts and Sciences, the place where St. Peter's successor delivered his message of consolation. The Fisherman's next visit, by boat, and his next homily, from the sea.

June 2006

Two Stadiums, Two Battlefields

The planet’s biggest event opened yesterday in a lightweight Bavarian stadium, to culminate within a month in the same the place that saw Hitler watch Jesse Owens win a gold medal in 1936. The contrast between the Allianz Arena of Munich and the Olympic Stadium of Berlin illustrates the dilemmas that afflict a country forced to confront contemporary realities with ghosts of the past, but also the tensions that weigh upon a world at once united by spectacle and fragmented by memory. (Photograph: Duccio Malagamba)

Luis Fernández-Galiano

Two Stadiums, Two Battlefields

In Munich , spectacle without memory; in Berlin , memory without spectacle. The two main venues of the World Cup of Germany, where the championship opens and closes, are architectures so opposed one would think them deliberately orchestrated to reveal the two faces of the host country. While the Allianz Arena is light, colorful, and suburban, posed on the landscape like a festive airship, the Olympic Stadium is heavy, grayish and urban, its monumental porticoes rising over a solemn esplanade. Whereas the Munich facility is a new building, clad with the innovative technology of inflatable pillows of ETFE (ethyltetrafluoretylene) that change color with lighting like a discotheque dance floor, the Berlin work is the remodeling of a historic stadium, one that adds a canopy over the grandstands but otherwise maintains the archaic gravitas of limestone and the axial severity of elemental geometries. And if Herzog & de Meuron's stadium is shaped like a pot with three steep stands and a roof that nearly closes on the boiling crowd, the one designed by Otto March almost a century ago (completed in the 30s by his sons Walter and Werner and now adapted by Volkwin Marg of the firm Von Gerkan & Marg) shows the gentle slope and the distance between audience and field that characterize track-and-field facilities, an inconvenience for soccer along with the tiers being interrupted by the Marathon gate and visibility in the upper stand being much diminished by the tree-like supports of the canopy's unclosed ring.

This architectural Jano is of course a portrait of Germany (although the two faces may represent the reverse of what they initially seem to), and at the same time offers a built oxymoron that symbolizes the schizophrenic contemporary tension between globalization and identity, spectacle and memory. At first glance, the cushioned, polychromatic globe in Munich is a futuristic, hyper-technological construction that ought to incarnate the optimistic spirit of Angela Merkel's new Germany . However, the impeccable geometrical logic, the exact functional definition and the lightweight insertion in nature make this colorful, pneumatic stadium a masterwork of canonic modernity, and its spectral immateriality the best vaccine against the ghostly viruses of an ominous past. One cannot help thinking that its classicism à rebours is a deliberate distancing from the random aesthetics of masts and canvases that Günter Behnisch and Frei Otto used to build Munich's Olympic Stadium in 1972, but that particular technical and social choreography sought to exorcize the grave, Wagnerian severity of the Nazi mass rallies with the same tools of lightness and transparency as the Allianz Arena.

The stone peristyle of Berlin , for its part, barely altered by the new canopy, would seem to express the classicist sensibility of old Germany . But its subjection to the rhetorical monumentality of Hitler's architecture, sacrificing functionality to the ceremonial axis that fractures the grandstands and the roof, makes its historicist traditionalism an anti-classical statement, one which otherwise refrains from questioning the theatrical urbanism of the Nazi period. This is perhaps the most contemporary attitude in a country that has replaced the embarrassment of guilt with a distracted acceptance, and which after the fall of the Berlin wall has occupied old Nazi buildings – from the headquarters of the Luftwaffe, now turned into the Finance Ministry, or the old Reichsbank, now housing Foreign Affairs – without the scruples or feelings of reticence that formerly plagued Germans when faced with the phantoms of their past. Only by considering this can we understand the naturalness with which they have remodeled the venue of the 1936 Olympics, the very place where Leni Riefenstahl filmed Olympia – the propaganda documentary that best presented Nazi ideals and aesthetics – and where Albert Speer put up the same cathedrals of light that had graced the Nuremberg party congress of 1934.

The dramatic dilemmas of Germany are also in a way those of Europe , and indeed of all nations afflicted by the antithetical impulses of amnesic adaptation to global homogeneity on one hand, and memory-driven defense of historic uniqueness on the other. In Munich , a Basel-based partnership known for its artistic and experimental profile – which previously gave the Bavarian capital the Goetz Museum and the Fünf Höfe arcade – has created an icon for the city's two football clubs (Bayern and TSV 1860), as well as for the national team. This icon lights up like a cushioned beacon, rising in the landscape of highways like a magical abstract landmark that arouses emotional identities and aesthetic emotions in a single stroke. In Berlin, a Hamburg firm with a more technological, corporate profile – which already had stadiums in other German cities in its track record – has remodeled a Nazi emblem without altering its urban presence, limiting its intervention to covering the tiers and introducing elements of a modern sport venue, from comfortable seats to press rooms and VIP boxes, homogenizing its program amenities while limiting symbolic regeneration to informative signs in perimetral porticoes and an interpretation center in the Langemarckhalle, a building shaped like an Egyptian temple located next to the stadium where the Nazis paid tribute to heroes fallen in battlefields. Paradoxically it is the more generic project, the one carried out in the more anonymous environment, the one that is ultimately more unique in form and has greater attraction for our society of spectacle. All this while the confrontation with an urban piece overwhelmed by the weight of history ends up in a lethargic trivialization and a docile subjection to memory that harms both its functional quality and its emblematic appeal.

For a whole month we were glued to the television screens for these sport battles that for the Nazis were a preparation for war, and which for us are a ritualized combat that replaces military conflict with symbolic warfare. After all, maybe it is true that spectacle unites us and memory separates us. If this is so, then maybe we should all celebrate the amnesic unanimity of football, and trust that its geometric beauty will protect us from the phantoms that still stir in the historic back room of national quarrels and identity wrestlings.

May 2006

The City is a Tree

The heated public debate on the refurbishing of Madrid’s Paseo del Prado reminds politicians and urban planners about the communal and ecological dimension of the city, a humanistic vision of the environment to which the recently demised Jane Jacobs dedicated her life and work. (Photograph: Uly Martín)

Luis Fernández-Galiano

The City is a Tree

The city is not a tree. This was the title of the 1965 article in which Christopher Alexander explained that urban design cannot come about in a simple process of successive decisions that fork out like branches. The city is a semi-lattice, he said, and this mathematical term meant that urban form stems from a tangled fabric of choices and chances. Such rejection of the tree pattern was a critique on the technocratic mechanistic order, as well as a defense of the complexity of urban organisms, so the negation of the computer tree paradoxically constituted an affirmation of the biological tree: in its thermodynamic and metabolic dimension, the city is a tree, its growth processes have both the vigor and the fragility of the living thing, and its contrived alterations through pruning and grafting have to be done with a gardener's knowledge and caution. Faced with the colossal mutation and metastasis of the metropolis, we cling to those slow, vegetal certainties in the same way that we grab hold of the paled memories of childhood, and we rise up in rebellion when the scalpel of the planner approaches the luxuriant, shady heart of the city.

When Alexander wrote, the modern certainties had already begun to fade, and the following year they got a definitive slap in the face with the appearance of the mythical books of Aldo Rossi and Robert Venturi, which opened the doors to postmodernity. José Luis Sert – whose retrospective exhibition inaugurated in Barcelona 's Miró Foundation is now in La Lonja of Palma de Mallorca – had published Can Our Cities Survive? in 1942, but this first presentation in English of the canonical urban theses of the fourth CIAM (International Congress of Modern Architecture), held in 1933, soon gave rise to an in-depth revision of the modern creed. This revision centered on recuperating the symbolic monumentality advocated by the historian Sigfried Giedion and on returning to the human scale preached by the critic Lewis Mumford. These were the wickers with which urban design was woven in Harvard in the 50s, a new discipline presented in society in 1956 through a famous encounter – remembered half a century later with a monographic issue of Harvard Design Magazine – that Sert, as dean, organized with the purpose of contributing to the revitalization of American urban centers, then physically gutted by transport infrastructures and socially devastated by the exodus of the middle class to residential suburbs.

A participant of that meeting was an architect's wife who was a writer and editor at Architectural Forum but otherwise lacking in college education, who in time became very famous for her successful confrontation with the all-powerful Robert Moses, chief urban planner of New York, on the issue of the Lower Manhattan Expressway, an overpass that would have destroyed her chosen neighborhood, Greenwich Village. In favor of the unpredictable and heterogeneous dense city (that mixed old and new constructions, rich and poor inhabitants, and vehicles and pedestrians in a permanently changing urban choreography), and therefore critical of Mumford's fixation with the garden city, this woman who Moses and Mumford looked down on as a housewife (the latter called her ‘Mother Jacobs' and the former attributed all opposition to his project to “a bunch of housewives”) published a book in 1961 that changed American urban planning, putting an end to the dominant orthodoxy of the so-called ‘urban renewal': the demolition of old neighborhoods to replace them with high-rises and apartment blocks, scattered between grass meadows and highway knots. The Death and Life of Great American Cities was at once a denunciation of insensitive urban planners and their political patrons, a salute to community participation as an instrument of societal defense against urban outrages, and a preamble to subsequent texts of hers about urban economy from an ethical and organic angle. A year later Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, and since then, movements for the protection of nature have been in tune with this abrasive activist's efforts to protect the diverse and complex vitality of urban ecology.

Jane Jacobs died in Toronto on 25 April (she had been living in Canada since 1968, when she left the United States to save her sons from being drafted for Vietnam), the day after El País published the attack of Carmen Thyssen on Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón regarding the refurbishing of the Paseo del Prado. The protest sparked one of the most impassioned and bitter urban controversies of the recent past. The entire spectrum of the media was mobilized, crowds demonstrated in support of the baroness, and the mayor of Madrid withdrew provisionally, delaying decision-making on the project by six months. Of course, Carmen Thyssen is not Jane Jacobs, because the Spaniard's fame and fortune guarantee her the visibility and audience that the American had to work hard for through her writings, and Gallardón is not Robert Moses either – more worthy of the title would be the engineer of the M-30 ringroad, Manuel Melis, since the architect of the Paseo del Prado, Álvaro Siza, is quite unlikely to take on such a demiurgic role. But the fact is that both the public echo sparked by the baroness's voice of alarm and the denigrating treatment given her remind one of the writer's thorny campaigns in defense of the existing city against the dreams or nightmares of the modern urban planners.

It is not easy to accept a woman without technical credentials daring to challenge so many influential men, bringing together a political mosaic that includes members of the conservative party as well as ecologists or socialists, and galvanizing public opinion against a project endorsed by the refined wisdom of the Porto master, legitimized by a troop of professors, and moved by a well-intentioned determination to reduce vehicular traffic and create a garden where there is now a street. But the solution adopted so radically distorts the city's lazy lines, and so substantially alters current traffic patterns and distribution of tree clusters that it threatens to turn possible advantages into certain damages, and questions the Hippocratic maxim that architects are always supposed to abide by when doing surgery on the city: primum non nocere. In any case, the debate is so sprinkled with unwarranted condemnations, so contaminated by the climate of sectarian animosity that currently dominates the country's political and media scene, and so removed from what Azaña called ‘tempered regions of the spirit' that any judgment must expect to be received more as a product of vested interests than as a fruit of conviction. Could our admiration today for Moses, Mumford or Jacobs have been possible when they were fighting one another in the urban trenches? Is it possible to appreciate Siza's architectural work, Gallardón's political profile and the baroness's civic activism all at the same time? Or must we wait for the cooling of passions that only time and distance can give? On the Paseo del Prado, a lost and found grove awaits the verdict of public opinion: if the city is a tree, let it be proven there.

May 2006

It’s the Economy, Ecologists!

The continuous increase of the oil price – triggered by the multiplication of demand rather than by occasional supply crises – opens a historic period of energy shortage that shall stimulate saving and the use of alternative sources, inviting new reflections in the fields of sustainable architecture and urbanism. (Photograph: Chad Ehlers/Alamy)

Luis Fernández-Galiano

It’s the Economy, Ecologists!

There is no ecology without economy. Beyond the etymological relationship, which places both sciences on common grounds, transfering its logos and its nomos to the shared oikos of our residence on earth, the green science is inconceivable without the melancholy science. Seen from the ‘fiercely human' viewpoint of architecture, the inhabited nature and the artifice of the market are interwoven like warp and weft. But environmental issues are often addressed skipping through the rough territory of financial issues, ignoring or underrating the fact that most of the decisions which shape the world are taken within that frame. At least for this reason, the advocates of sustainable architecture and urbanism should always keep in mind the motto that the political strategist James Carville used in Clinton 's campaign during the 1992 elections, and that has become a catchphrase in the American debate. “It's the economy, stupid!”

Architects talk about sustainability these days not because they have embraced the green creed, but because oil is expensive. This subordination of ideas to facts is not a reprehensible case of opportunism, but a legitimate mechanism of adaptation to a changing world, necessary to ensure the evolutionary survival of social groups and their members. The Marxian verification that conscience follows experience, rather than the other way around, is undoubtedly a criticism of philosophical idealism, an expression of the self-interested nature of knowledge, and a condemnation of the phantasmagoric and intoxicating character of ideology, but also a timely description of adaptative learning. The current fervor for ecological architecture faithfully reproduces that of the seventies, though with some significant variations. As then, it is triggered by the oil shocks that in 1973 and 1979 shattered the energy bases of the economy; but unlike what happened in that decade, contemporary green conscience arises – for now – within a context of economic growth and real-estate boom, where the cold war has been replaced by the conflict with a Muslim world lavish in oil and gas reserves, and in a planet that witnesses the emergence of giants such as China or India with colossal demands for energy, while its price does not prevent the buildup of greenhouse gases that cause global warming.

Within this geopolitical context one can of course argue that buildings and cities are responsible for the greater part of energy consumption, because if we add the cost of air conditioning, lighting and transportation to the energy costs of construction – be it of buildings or urban or territorial infrastructures –, any estimation method shall produce a result of over 50 percent. However, to presume because of this that architects are the inevitable protagonists of the energy dilemmas sparked by the current crisis (in its double dimension of shortage and climatic impact) is a mirage. The decisions that are going to shape our future will be taken in the field of macroeconomics, against the backdrop of the peaceful or military struggles between states for energy, raw materials and water, and in the absence – at short or mid-term – of a global governance that may settle conflicts or safeguard the system's balance. In this scenario of partially self-regulated instability it is easy to forecast changes in the demographic flows and the forms of occupation of the territory spurred by political or economic mutations, but it would be foolish to speculate on their magnitude and their direction, being part of a panorama of technical and climatic uncertainty.

If compared to the resistant and alternative ingenuity of the solar houses of the seventies, with their post-hippy worship of craftwork, their preindustrial defense of autonomous utopia, and their luddite fascination for everything primitive, the contemporary crop of built sustainability has the inequivocal taste of intricate prosperity, normative bureaucracy and symbolic simulacrum: Robinson Crusoe has been replaced by a technocrat. Sustainable construction is today a roaring field, which has its own fairs and congresses, its own magazines and its own prizes, a field nurtured by the demanding regulations and generous subsidies of governments, and a field that tries to make up for its aesthetic handicaps with rankings, homologations and green tags whose ethical aura can give social legitimacy and public exposure to the authors and the works. Reinforced by the presence of corporate firms whose green credentials are an extension of their technological sophistication, and by offices that place their work within a more social perspective, this field is today a meeting point between professional bureaucracies and emerging explorations, but still not a disciplinary territory marked by certainties and conventions.

With all of this, it is paradoxical that the work most quoted as a representative of this new attitude is a New York office skyscraper, the Condé Nast building in 4 Times Square, a project by Fox & Fowle that served as prototype for the development of the LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) ratings, the standards created in 2000 by the United States Green Building Council; leaving aside its disappointing aesthetic result, the simple fact of using the high-technology of the skyscraper as an emblem of green architecture – for instance, on the cover of the supplement of The Economist devoted to the subject in December 2004 –, shows to what extent the ecological concerns have seeped into the daily practice of the profession, but also how the means used to address them are simply technological gadgetry and the upgrading of mechanical services. And also a revealing symptom of the power of the economic context in which buildings are produced is the fact that The New York Times headquarters on the same site, with Piano as architect and a commitment to environmental responsibility, had to give up the LEED certification when faced with the financial costs of building in the heart of Manhattan .

Economy, along with politics, imposes its iron law upon technical and social choices, setting guidelines with its trends and marking individual and collective life with its cycles. Those of us who graduated in the summer of 1973 entered the professional field coinciding with the Arab-Israeli war of that fall, which triggered the first oil crisis, and our initial critical and architectural skirmishes where inevitably conditioned by the climate of concern for energy and the economic standstill caused by the rise of fuel prices; a material and ideological context that would be reinforced in 1979 with the Iranian revolution and the second oil crisis, but that would gradually weaken in the following years to later fade away entirely in the second half of the eighties, with the drop in barrel price and the acceleration of economic growth. This situation has been maintained since, with no further frights than that produced in 1990 by the ephemeral invasion of Kuwait by Iraq , with the oil reaching in 1999 prices lower than those of 1974. In the last seven years, however, the barrel price has increased sevenfold.

This context of energy shortage – added to the acknowledgment by scientists of the planet's global warming – has given rise to a new ecological conscience, which takes up issues and authors that had been forgotten during the decades of prosperity, and that for those of us who have lived during the previous period has the narcotic aroma of the déjà vu and the bittersweet taste of lost causes. With more optimism of the will than pessimism of the mind, the green agenda is presented as a renewed secular ethic, but often becomes rather an instrument of political correction in the public relations of governments, institutions or companies. Oblivious to the political or economic context of environmental decisions or perhaps meekly resigned to impotence when faced with the titanic forces that shape our world, the green tag ends up becoming an alibi that endows with the patina of good intentions architecture and urbanism, two activities that cannot be easily separated from the violence they exert over nature.

Construction always uses non-renewable resources and increases the world's entropy. Architects have a faustic pact with excess, so they only surrender to the green syndrome when economy enters recession, and then become advocates of zero growth, austerity and renovation, to later return to messianism and big dreams as soon as consumer confidence recovers. During the present period of transit, with expensive fuels and a booming economy, sustainable architecture is no more than a cocktail of trivial technology that combines thermal sensors, heat pumps and solar panels with old-time recipes on natural lighting and ventilation, orientation and solar protection or thermal insulation and inertia. But if bad comes to worse, all this sweet fantasy will give way to the real dilemma: to build or not to build? Because in the end the only ecological architecture is that which is never built, and the only green architect is the one who refuses to increase the planet's entropy. Meanwhile, us architects have a transparent rather than vested interest in economic growth and in the boom of construction and public works.

April 2006

Spanish Landscapes

The dissolution of Marbella’s Town Hall has placed urbanism at the center of the political debate, and the first signs of a weakened real estate market puts construction on the very axis of the discussion about the economic and territorial model of a country that seems doomed to choose between prosperity and the landscape. (Photographs: Cordon Press; Marc Ritchie)

Luis Fernández-Galiano

Spanish Landscapes

Marbella has undergone an exorcism. With the dissolution of the City Council and the imprisonment of those responsible, political and judicial Spain tries to drive away the all too familiar demons of speculation and corruption, expel the evil spirits of the healthy body of a young democracy. But Marbella is really the extreme case of a common disease: the penal pathology may reach its worst there, but the symptoms are everywhere. As much the coasts as the edges of cities, and even rural areas that up to now have been intact, are suffering a historic mutation driven by the economic boom and the new demands that come with it. Because of the pain we feel at the thought of the accelerated disappearance of natural landscapes, we tend to describe this process of colonization in medical terms like infection or metastasis. But this impetuous growth can also be interpreted as a result of the vitality of a prosperous and hedonist society that multiplies its needs and desires with impulsive impatience. The territory is always a physical picture of the culture that has molded it and, whether we like it or not, Spain's new landscapes accurately reflect what we are today: well-off, smug and vulgar.

The uncontainable advance of asphalt, just like the real estate bubble itself, is not only a product of corruption or greed. It comes from a social demand for first and second homes that low interest rates and lifelong mortgages have made financially accessible, and that unanimous motorization and the new transport infrastructures have made geographically accessible. In the nineties, urbanized land in Spain increased by 25% (a good 50% in Madrid or on the coast of Valencia and Murcia ). Everywhere, this spread of cement and brick arouses the same contradictory reaction: on one hand, despair at the destruction of the environment; on the other, frenzied acquisition of seaside apartments or houses in the low-density developments of urban peripheries. The town planner Ramón López de Lucio recently took the trouble of documenting the new residential landscapes in the outskirts of Madrid , and the result was as depressing as it was stimulating. To begin with, the low density of this urban environment pushes all activity to the large commercial centers that serve to finance the costs of urbanization, but privatize the collective domain and leave residual public spaces exposed to vandalism. But at the same time, the conventional developments of row houses or low-rise blocks of apartments that form the greater part of the new compounds are uniformly spacious and functional in design, and carried out with a very reasonable degree of material quality. They are homogeneous in their lifeless, self-withdrawn triviality, yet solid, well-equipped and luminous.

Those of us who write in newspapers are in general too old and too elitist to understand that the indifferent anomy of these new urban landscapes do not make them any less desirable, that their abysmal visual mediocrity does not in any way decrease their market value, and that the absence of collective activity in them is not as important to the home buyer as the quality of window frames or the tiling of floors. Urban life has been replaced by suburban life, a way of occupying space and time that also characterizes all the recent developments on the coasts. These new forms of relating to one another and consuming are for many an additional attraction. Never mind if there is no street life; there will be life in a commercial center, around a community swimming pool, or in a backyard barbecue party. Millions of Spaniards have with their mortgages voted for the faded suburbanity of the peripheries and for the massive vacational colonization of the coastline. Both are expressions of economic prosperity, but also of a political democracy that gives governing capacity to municipalities that are powerless in the face of the colossal forces that shape the territory. They may be routinely greedy and occasionally corrupt, but these forces feed on the freedom to choose of real estate buyers, and the landscapes they have shaped faithfully portray the Spanish society of democracy. Moreover, they are electorally devastating, as we have seen in the caricatural case of the Costa del Sol, but also as we witnessed when Britain's New Labour was forced to shelf the Urban White Paper drawn up by Lord Rogers, which included a call to refrain from building on ‘greenfields' (previously undeveloped land), a recommendation that would have antagonized the rising middle classes of the cottage and the SUV that currently make up the demographic and electoral support of any European political center.

In a recent exhibition in Madrid's Círculo de Bellas Artes, the architect César Portela showed his interventions in two Galician landscapes of singular beauty and emotion, The carballeira of Lalín and the isles of San Simón and San Antonio in the estuary of Vigo, two intact natural places which tourist and holiday bulimia has not yet devoured with its unstoppable machinery, and the exhibition's timing with the Marbella crisis made one contemplate the contrast between the way we were and the way we are. The carballeira , a spot in the woods presided by a monumental granite table where 150 neighbors come together for communal celebrations, is a space of archaic poetry that evokes the popular fiesta and the sacred mystery, but also speaks of the frozen time of the village and the stifling rigidity of superstition and habit. The isles of the estuary, the location of an old lazar house and jail, stand out for their melancholic nature and the romantic splendor of their essential constructions, but in this lost world of ashlars and lichens that the architect barely touches with accents of glass, beats an ominous past of illness, punishment and isolation. In contrast with the trivial, ostentatious landscapes of Marbella , the aching beauty of these faded places beckons to us with the magnetic force of the abyss of time. But if we look straight and without the moist veil of aesthetic emotion, we will realize that the new landscapes of narcissist prosperity portray us more accurately than those exact traces of the past, which are preserved only like insects in amber. Hypocritical reader, Marbella is all of us.

April 2006

Inconspicuous Mastery

The Bank of Spain has wrapped up its monumental headquarters at the Plaza de Cibeles by closing up the square with a corner built by Rafael Moneo: a project that so respects the language of the original building that it will go unnoticed by nearly everyone, an admirable exercise in subordination to context. Coinciding with its 150th year of existence, the institution holds an exhibition presenting the enlargement project and the entries to the 1978 competition that gave rise to it.

Luis Fernández-Galiano

Inconspicuous Mastery

It is harder to go unnoticed than to attract attention. And at the Plaza de Cibeles, at the symbolic heart of the Spanish capital, little less than impossible. Yet few of Madrid 's people will notice Rafael Moneo's recent enlargement of the Bank of Spain headquarters, however prominently its new corner on Alcalá wraps up the perspective of the Gran Vía. So faithfully does the addition take up the lines of the preexisting construction, that the distracted gaze will simply assume it was always there. Only those residents with particularly good memories will remember José de Lorite's building for Banca Calamarte, long covered as it was with canvases and torn down in 2002 to give way to what now concerns us, the recently finished facades of which—as in the first enlargement, drawn up by José Yarnoz in 1927—reproduce those of the original construction, an eclectic work of the architects Eduardo de Adaro and Severiano Sáinz de la Lastra that opened in 1891. And if now it takes a lot of attention to detect the sutures in the masonry, in a few years only historians will know that the categorical elevation on Alcalá is actually two elevations separated by more than a century.

Naturally, the essential lesson of this small work of Moneo is that one need not use the language of our times to expand a historic building. Heroic modernity established this lesson beyond doubt. To question this dogma of the 20 th -century avant-gardes is to scandalize the defenders of modern orthodoxy, who will probably raise their fists in several directions. For a start, they will point out that the project came about through a competition held back in 1978, and that it therefore goes by the postmodern revisions then in vogue – subsequently discredited – instead of addressing contemporary concerns. They will also draw attention to the fact that as much the unmistakable interior sections as the geometrizing of the decorative details of the façade are evidence of the architect simultaneous sliding toward his own formal language and ironic distancing from classicist codes. Finally, they will stress that the extension rises on so small a piece of the city block taken up by the Bank of Spain that it cannot possibly aspire to offer a modern counterpoint, that it can do no more than complete the preexisting through imitation.

But none of this is entirely true. The competition is indeed remote in time. Suffice it to remember that the central bank has seen four governors since. But the matter came to a dead end when Town Hall denied the institution permission to tear down Lorite's work, a mixed-use building containing offices and apartments that was completed in 1924 and vacated in 1974, after its acquisition by the Bank of Spain. Construction of the corner was delayed for over a quarter-century, but has now finally been carried out in accordance with a definitive project that, while significantly improving the initial proposal, reaffirms the starting hypotheses, which revolve around completing the block with the same language. In the second place, the sections reveals some dissonances that are modern, but these are clearly less important than the symmetrical classicism of the floor plans, and the convincing decomposition of ornamental elements into planes – except for the new caryatids, entrusted without too much luck to the sculptor Francisco López Quintanilla – is closer to Art Déco than to the irony of Venturi, whose playful extension of London's National Gallery in 1986-1991 will be in the mind of many, even as it places itself in a territory that is methodologically much removed from this severe project. Finally, the dimensions of the operation invite but do not necessarily demand contextual discreetness, as several of the 1978 competitors eloquently expressed through a whole gamut of proposals that ranged from the rough modern militancy of Corrales & Molezún or Eleuterio Población to the postmodern provocations of MBM, passing through the schematic historicism of Javier Yarnoz, son of the author of the first extension and himself the author of the less fortunate construction, carried out in the period 1969-1975, on the streets Madrazo and Marqués de Cubas.

Though a small work, both the importance of the institution and the quality of the original building – where the historian Pedro Navascués has with a critic's sharpness detected the coexistence of the establishment's two characters: on one hand its industrial nature on the sober granite plinth, on the other hand its representative role, this in the solemen arches and “Venetian” columns of the main floor, rendered in limestone; a dichotomy that is repeated in the sequence of interior spaces, the more laconic ones along the axis of the corner facing Cibeles, the more palatial ones behind the monumental entrance on the Paseo del Prado –make Moneo's enlargement a uniquely prominent project, one we cannot help comparing to his other interventions along the Prado-Castellana axis, in all of which he has had to confront patrimonial dilemmas, from the exemplary deference to a preexisting mansion in the Bankinter case to the less perfect struggle with Villanueva's work in the Prado Museum (possibly more censurable than the stubbornly controversial brick cube in the Jerónimos church cloister), not to mention the intelligent use of the Palacio de Villahermosa facades for the Thyssen Museum and the joining of the rhetorical hypostyle of Atocha Station with the marquee of Alberto del Palacio.

In perspective, it may be that the most silent works are what end up capping greater critical attention, and that the two banks designed in the sixties – Bankinter and Banco de España – will be judged as being more significant in the course of architecture than the two museums or the station nearby, the mass use of which give them greater public visibility. The long due closing of the Banco de España block has been described in this daily under the title “The Caruana Corner,” and indeed one is tempted to think that the parallel history of the institution and the building has a worthy crowning in its culminating under a governor – one trained in that same public secondary school of Teruel that with teachers like José Antonio Labordeta produced graduates like Juan Alberto Bellock, Federico Jiménez Losantos, or Manuel Pizarro – who is as excellent as he is discreet, with an international career comparable in the economic field only to Rodrigo Rato's, and who in the shaken national wheel has managed – unlike Greenspan and Collina – to act without protagonism, in the manner of good arbiters, as befits the regulatory function of the entity he heads. In the city and in life itself we are constantly coming across works and persons that go unnoticed, not so much because of their low profiles but because of their prudent subordination to an urban or institutional context. It is an attitude that calls for elegance in life and professional skill: no one said it would be easy to fly under the radar.

March 2006

Motor Works

The start of the Formula 1 season is a perfect time to remember the romance of architecture and the automobile, a romance recently rekindled through emblematic buildings designed by Norman Foster for McLaren, Ben van Berkel for Mercedes, Zaha Hadid for BMW, Jakob & McFarlane for Renault, or Massimiliano Fuksas for Ferrari. (Photograph: Klemens Ortmeyer)

Luis Fernández-Galiano

Motor Works