Two Stadiums Two Battlefields

Summer

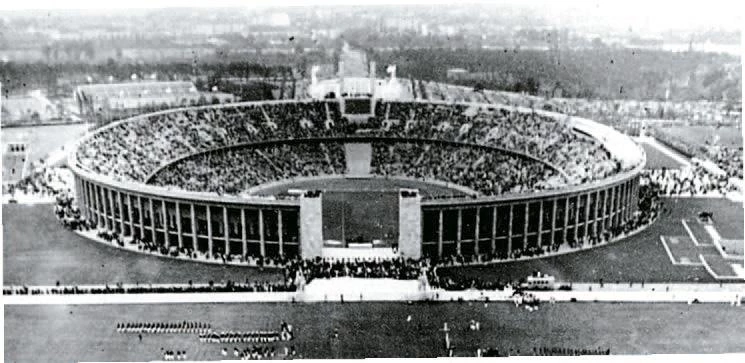

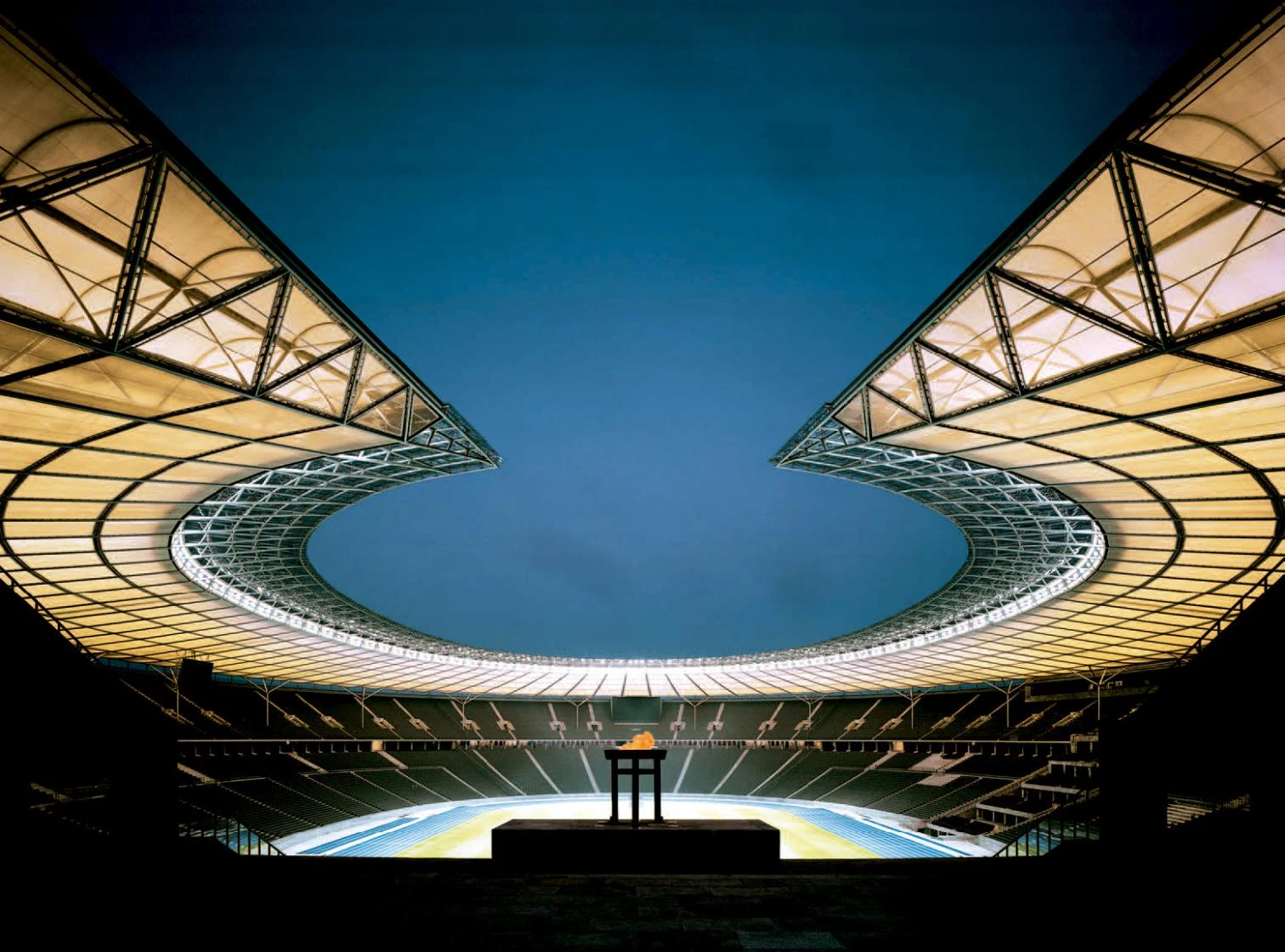

In munich, spectacle without memory; in Berlin, memory without spectacle. The two main venues of the World Cup of Germany, where the championship opens and closes, are architectures so opposed one would think them deliberately orchestrated to reveal the two faces of the host country. While the Allianz Arena is light, colorful, and suburban, posed on the landscape like a festive airship, the Olympic Stadium is heavy, grayish and urban, its monumental porticoes rising over a solemn esplanade. Whereas the Munich facility is a new building, clad with the innovative technology of inflatable pillows of ETFE (ethyltetrafluoretylene) that change color with lighting like a discotheque dance floor, the Berlin work is the remodeling of a historic stadium, one that adds a canopy over the grandstands but otherwise maintains the archaic gravitas of limestone and the axial severity of elemental geometries. And if Herzog & de Meuron’s stadium is shaped like a pot with three steep stands and a roof that nearly closes on the boiling crowd, the one designed by Otto March almost a century ago (completed in the 30s by his sons Walter and Werner and now adapted by Volkwin Marg of the firm Von Gerkan & Marg) shows the gentle slope and the distance between audience and field that characterize track-and-field facilities, an inconvenience for soccer along with the tiers being interrupted by the Marathon gate and visibility in the upper stand being much diminished by the tree-like supports of the canopy’s unclosed ring.

This architectural Jano is of course a portrait of Germany (although the two faces may represent the reverse of what they initially seem to), and at the same time offers a built oxymoron that symbolizes the schizophrenic contemporary tension between globalization and identity, spectacle and memory. At first glance, the cushioned, polychromatic globe in Munich is a futuristic, hyper-technological construction that ought to incarnate the optimistic spirit of Angela Merkel’s new Germany. However, the impeccable geometrical logic, the exact functional definition and the lightweight insertion in nature make this colorful, pneumatic stadium a master-work of canonic modernity, and its spectral immateriality the best vaccine against the ghostly viruses of an ominous past. One cannot help thinking that its classicism à rebours is a deliberate distancing from the random aesthetics of masts and canvases that Günter Behnisch and Frei Otto used to build Munich’s Olympic Stadium in 1972, but that par ticular technical and social choreography sought to exorcize the grave, Wagnerian severity of the Nazi mass rallies with the same tools of lightness and transparency as the Allianz Arena.

The Munich stadium by Herzog & de Meuron is a lightweight bubble that changes color depending on the team playing, alit on the landscape as a festive airship whose accesses choreograph the movement of the masses.

The stone peristyle of Berlin, for its part, barely altered by the new canopy, would seem to express the classicist sensibility of old Germany. But its subjection to the rhetorical monumentality of Hitler’s architecture, sacrificing functionality to the ceremonial axis that fractures the grandstands and the roof, makes its historicist traditionalism an anti-classical statement, one which otherwise refrains from questioning the theatrical urbanism of the Nazi period. This is perhaps the most contemporary attitude in a country that has replaced the embarrassment of guilt with a distracted acceptance, and which after the fall of the Berlin wall has occupied old Nazi buildings – from the headquarters of the Luftwaffe, now turned into the Finance Ministry, or the old Reichsbank, now housing Foreign Affairs –without the scruples or feelings of reticence that formerly plagued Germans when faced with the phantoms of their past. Only by considering this can we understand the naturalness with which they have remodeled the venue of the 1936 Olympics, the very place where Leni Riefenstahl filmed Olympia – the propaganda documentary that best presented Nazi ideals and aesthetics – and where Albert Speer put up the same cathedrals of light that had graced the Nuremberg party congress of 1934.

The dramatic dilemmas of Germany are also in a way those of Europe, and indeed of all nations afflicted by the antithetical impulses of amnesic adaptation to global homogeneity on one hand, and memory-driven defense of historic uniqueness on the other. In Munich, a Basel-based partnership known for its artistic and experimental profile –which previously gave the Bavarian capital the Goetz Museum and the Fünf Höfe arcade – has created an icon for the city’s two football clubs (Bayern and TSV 1860), as well as for the national team. This icon lights up like a cushioned beacon, rising in the landscape of highways like a magical abstract landmark that arouses emotional identities and aesthetic emotions in a single stroke. In Berlin, a Hamburg firm with a more technological, corporate profile – which already had stadiums in other German cities in its track record – has remodeled a Nazi emblem without altering its urban presence, limiting its intervention to covering the tiers and introducing elements of a modern sport venue, from comfortable seats to press rooms and VIP boxes, homogenizing its program amenities while limiting symbolic regeneration to informative signs in perimetral porticoes and an interpretation center in the Langemarckhalle, a building shaped like an Egyptian temple located next to the stadium where the Nazis paid tribute to heroes fallen in battlefields. Paradoxically it is the more generic project, the one carried out in the more anonymous environment, the one that is ultimately more unique in form and has greater attraction for our society of spectacle. All this while the confrontation with an urban piece overwhelmed by the weight of history ends up in a lethargic trivialization and a docile subjection to memory that harms both its functional quality and its emblematic appeal.

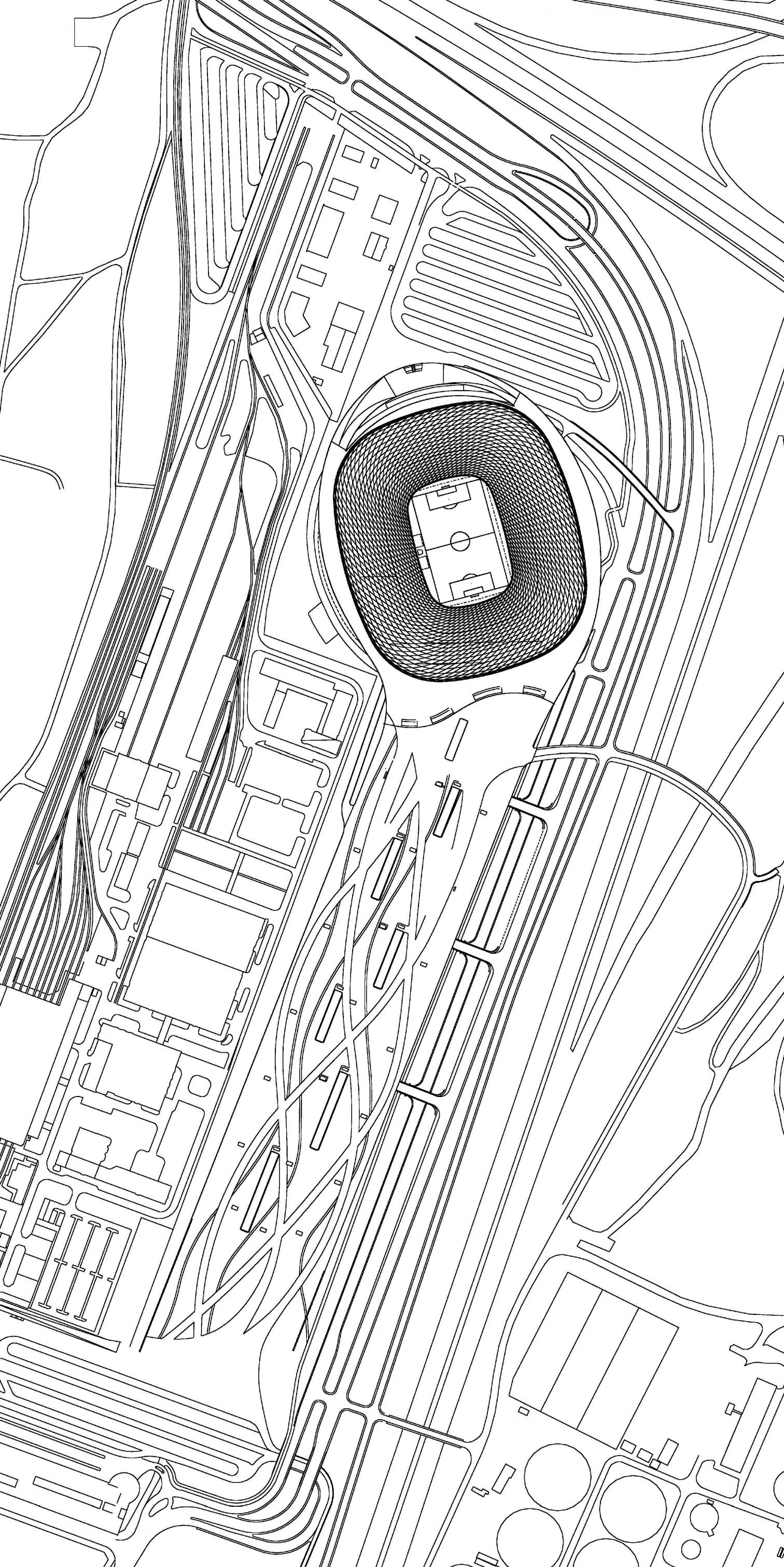

Von Gerkan & Marg have remodeled the Olympic Stadium of Berlin with a canopy resting on tree-like supports, interrupted by the Marathon gate axis, which crowns the heavy stone porticoes built in the Nazi period.

For a whole month we were glued to the television screens for these sport battles that for the Nazis were a preparation for war, and which for us are a ritualized combat that replaces military conflict with symbolic warfare. After all, maybe it is true that spectacle unites us and memory separates us. If this is so, then maybe we should all celebrate the amnesic unanimity of football, and trust that its geometric beauty will protect us from the phantoms that still stir in the historic back room of national quarrels and identity wrestlings.