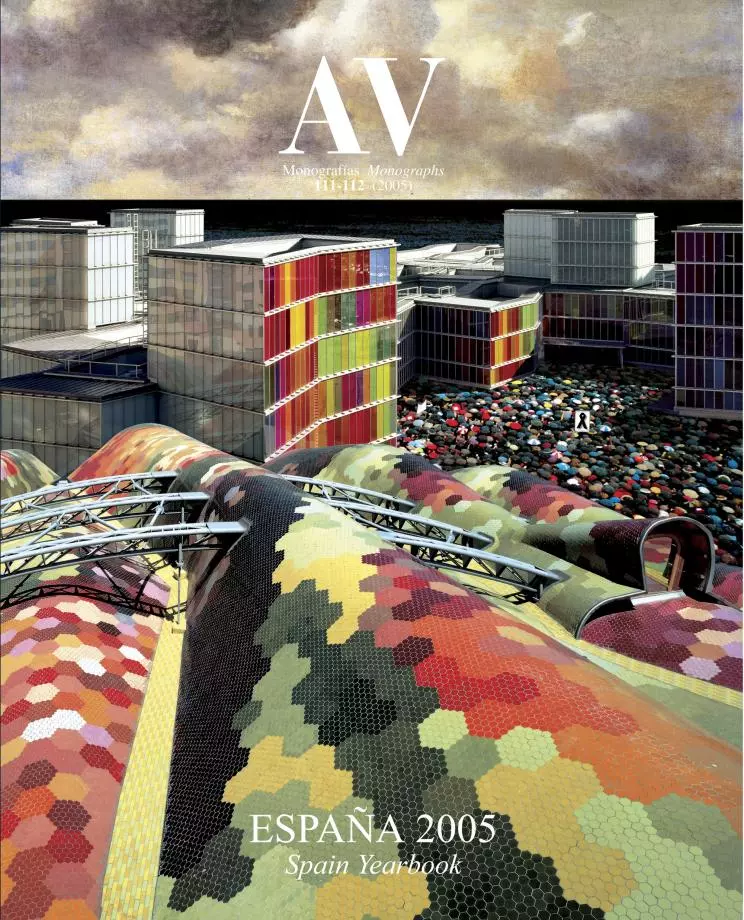

Football in a Quarry

Eduardo Souto de Moura, Municipal Stadium of Braga

In Europe, ballots have lost to football. The European Parliament elections coinciding with the start of the 2004 Eurocup in Portugal has shown, at least as far as television audiences are concerned, how politics cannot compete with sports. Surely the electoral candidates expected this, and they have not hesitated to incorporate football language into their campaigns, from the ‘Força Portugal’ of the governing coalition to the yellow and red cards used as political metaphors by the socialist or communist opposition: a Berlusconization of democracy that tiptoes on the non sancta relationship between sport clubs and political parties through the well-greased hinge of municipal urban-planning power. Sadly, such corrupt ties between football executives, local authorities, and construction entrepreneurs – which in Portugal has led to the arrest and subsequent provisional release of Valentim Loureiro, mayor of Gondomar and at the same time president of Porto’s Metropolitan Urban Authority and of the Professional Football League – seem to be all but endemic to the present capitalism of spectacle. Italy and Spain have seen numerous collusions between the lawn of the stadiums and the land of the city – the case of the recently deceased Jesús Gil is only the most picturesque and extreme of them all –, but the recent imprisonment of 1860 Munich’s president, for bribery related to the allocation of contracts in Herzog & de Meuron’s stadium, venue of the opening of the World Cup in 2006, proves that this is no exclusively Latin pathology.

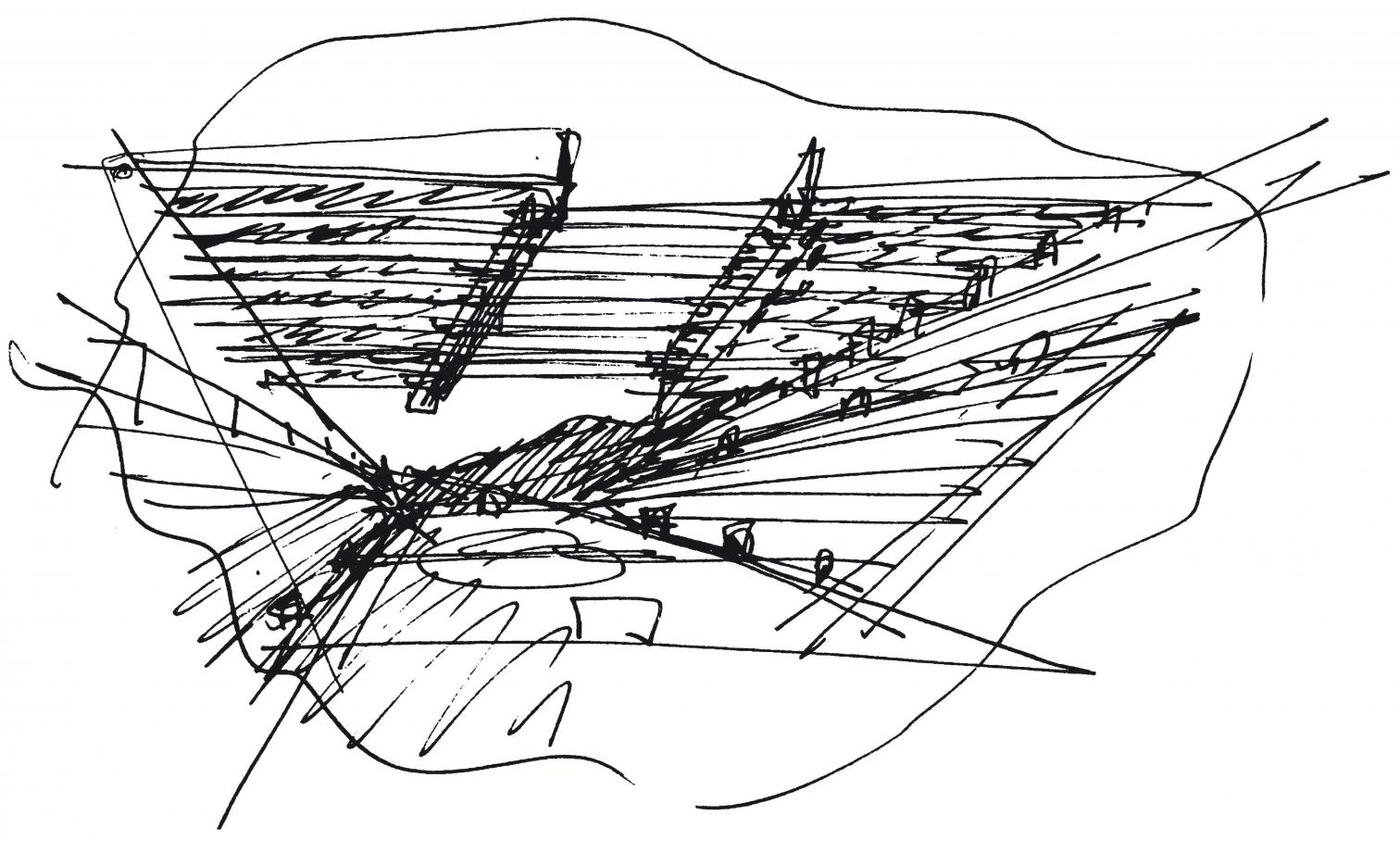

The architect proposed to place the stadium in an abandonded quarry, regenerating a decaying area with the new sports facility, whose section cleverly interprets the precipitous topography of the existing site.

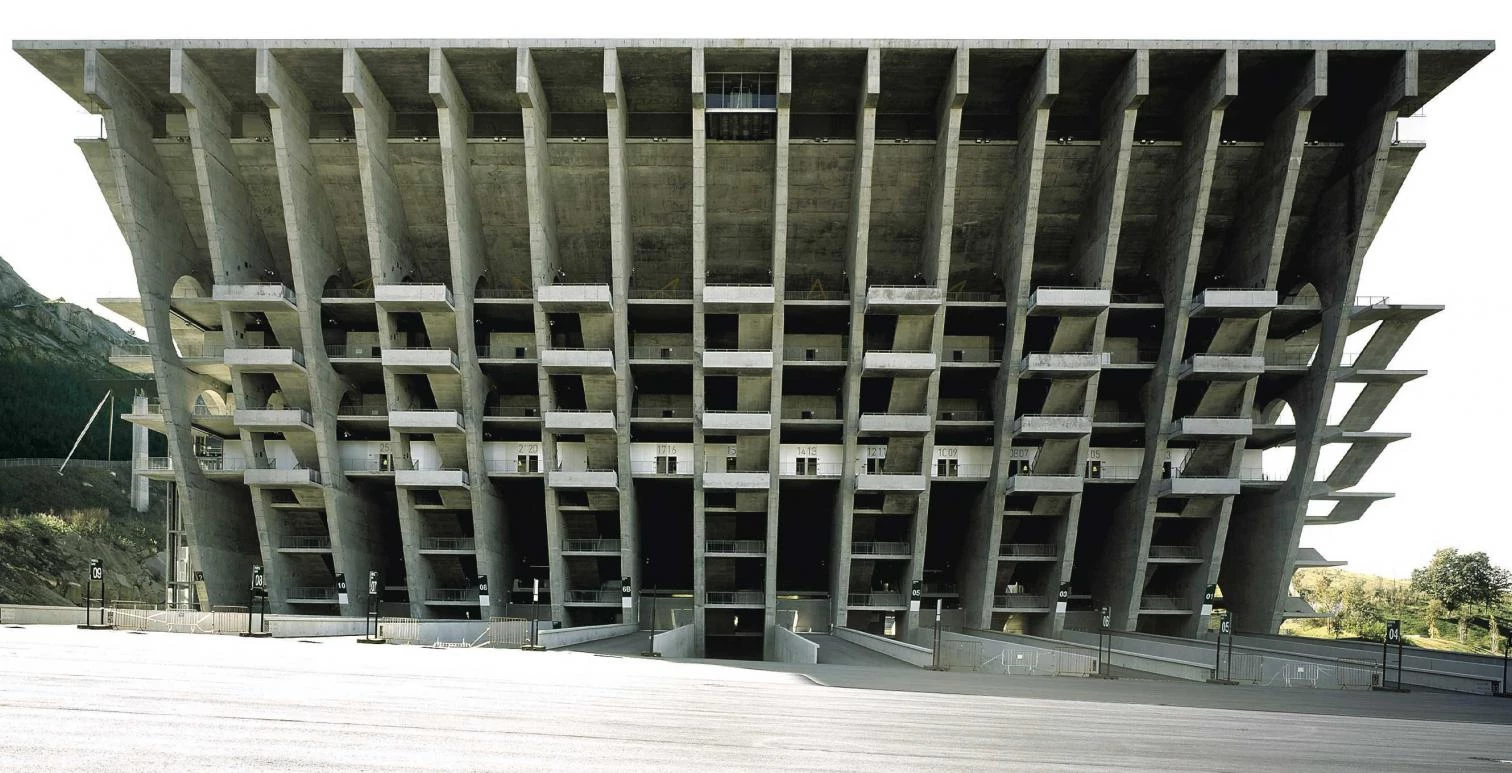

The municipal stadium of Braga, which happily has stayed clear of the epidemic of scandals, is without a doubt the finest architectural work that has risen in preparation for the event – for which three stadiums have been renovated and a total of seven new ones built –, and as much the circumstances of its conception as its location in the territory and its definitive design project throw light on the nature of both construction and contemporary sport. Linked to Braga’s designation as venue for two matches of the European championship’s preliminary phase, its origins illustrate that there are no big investments without big events. However extravagant it may seem, the best guarantee for the execution of a work is the promise of its being the scene of an event. Decided by the architect after official proposals for its situation on a river valley were rejected, the stadium’s unique location on the site of an old granite quarry recovers a marginal zone for the city while serving as a support for Braga’s future growth, thereby manifesting the territorial importance of infrastructures, which afterall are responsible for urban form. As for the project itself, with the two grandstands facing each other – one attached to the quarry cliff and the other held up by a rhythmic series of concrete walls –, connected by a suspended canopy and with no tiers behind the goals, it replaces the usual pot or candy box of fields of high emotional temperatures and puts instead a dry and monumental set for sport broadcasts, in recognition of the mediatic nature of contemporary football.

Of a rough beauty not far removed from the contrast between the rocky wall of the quarry that seals off one of its ends – the other end opens on to the distant landscape – and the demanding concrete geometry of the colossal civil work, Souto de Moura’s stadium is covered by a canopy that was initially proposed as a continuous sheet resembling Álvaro Siza’s concrete one in the pavilion of the Lisbon Expo, but was finally carried out with a discontinuous system inspired, according to the architect, by the suspended bridges of indigenous Peru. The marquise, which is interrupted in the rectangle of the playing field, wraps up its edges with rows of spotlights and gutters for the draining of water, which through gargoyles spill into two large sculptural gutters cantilevered from the cliff. The titanic walls of concrete that hold up the free-standing grandstand are lightened by the circular perforations that allow the transversal movement and by the musical elegance of the interspersed stairs, which are supplemented with a final module added for purely compositive reasons. The result is an origami-like weightlessness all the more enhanced by the immateriality created by the lighting at night. From the square in front of it come the spectators, who in order to reach the grandstand attached to the rock must cross a large hypostyle hall, with columns of cone-shaped capitals, that stretches beneath the grass of the playing field. Another square, built on the quarry cliff at a level 40 meters higher and conceived for VIP parking, provides access to boxes and press zones.

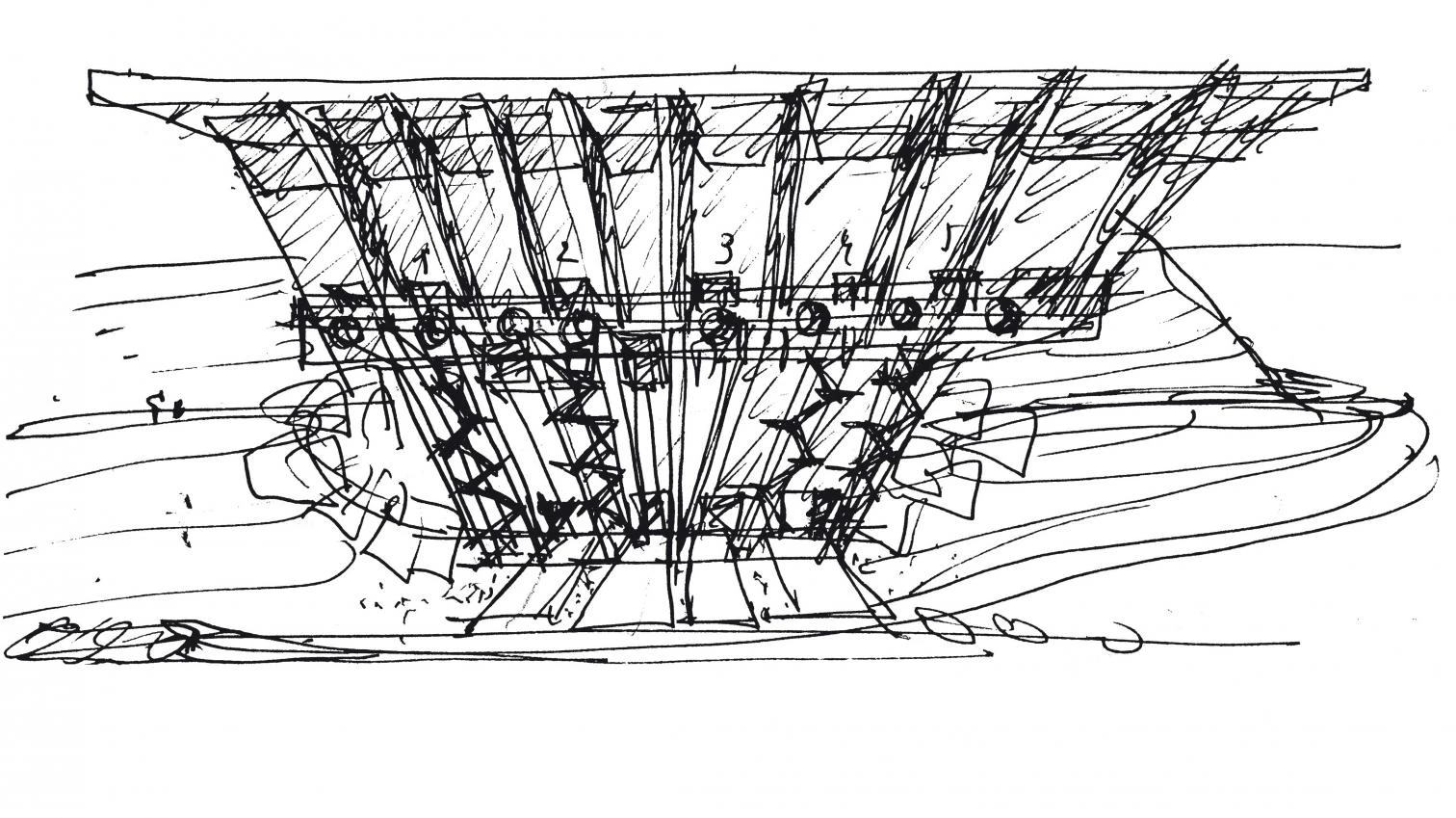

To adapt to the site, two grandstands rise face-to-face, one leaning on the quarry cliff, and the other freestanding, made up by a sequence of sculptural concrete walls that look heavy and weightless at the same time.

Eduardo Souto de Moura, who twenty years ago built in the then rural periphery of Braga his very first work, the market of Carandá, now renovated with amputations that, in his words, try to “avoid its succumbing to gangrene”, has returned to this city, situated halfway between Porto and the Galician border, to carry out what is his largest project, both in size and in symbolic dimension, combining, as it does, Brazilian scale – one inevitably thinks of the works of Vilanova Artigas or Reidy – with the media visibility of a venue of high sport competition. Always elegant, but in this case under the dramatic impact of size, the contrast between geometry and nature of his early houses is here placed at the service of territorial organization, in the same way that the typological innovation of the extruded stadium is subjected to the structural and visual logic of spectacle. This radical work in addition offers, in the suspended canopy overhead, a quote paying tribute to the master Álvaro Siza that makes us wonder if the so-called Porto school, with its conventional Távora-Siza-Souto genealogy, has after all some other basis than mere mutual friendship, even as this Portuguese project also recognizes some Brazilian father!

The canopies which shelter the public hang from a series of catenary cables fixed to the top of both grandstands, and which span a playing field whose short sides are unexpectedly open to the surrounding landscape.

With its laconic severity and laborious order, I want to think that the stadium has something of the stony discipline and choral mechanics that made Mourinho’s Porto win the 2004 Champions League and show to the world how grassroot football can be as successful as the import-export star sport of the likes of Futre or Figo. For its part, the failure of Queiroz’s galactic Madrid – predicted to me a year ago by António Lobo Antunes, as convinced as he was about the incompetence of his compatriot as about Camacho’s perfect adaptation to proletarian Benfica – may also have an architectural moral, proving as it does the sterility of fantasy and individual talent when not framed within a coherent strategy and system. Strategy and system are both stubbornly present in the work of Souto de Moura, who allowed false staircases, sculptural gargoyles, and any such adornments only after having taken the major decisions regarding the site and having drawn up the key structural lines of the project. Only after planning the season and building the team can the architect concentrate on the geometric and lyrical beauty of what is a very serious game.