The story of architecture can be written in books, but also performed on stages. What else are exhibitions showing works, careers, or episodes, often backed by a research effort captured in the setup and saved for posterity in the catalog? The latest major history of modern architecture, written by Jean-Louis Cohen with an ear alert to the beat of the times, gives considerable space and numerous illustrations to exhibitions, which are frequently as important as books or buildings in opening paths or setting patterns. If curatorship nowadays plays such an important role, it is because these ephemeral architectures of communication tell narratives that could well become canonical, defining for a generation or an epoch a plausible account of the period, an accepted hierarchization of protagonists and works, and an agreed sequence of events.

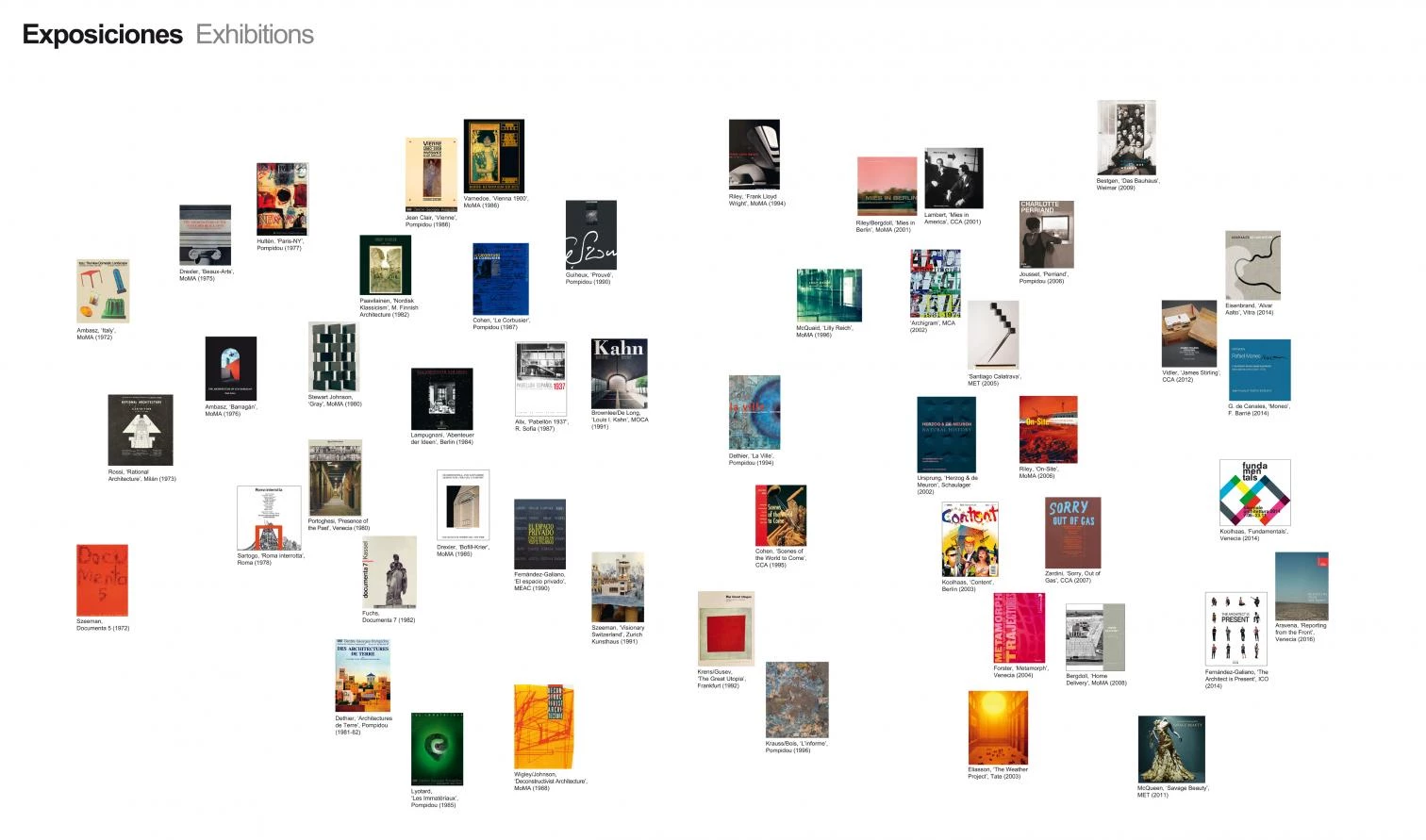

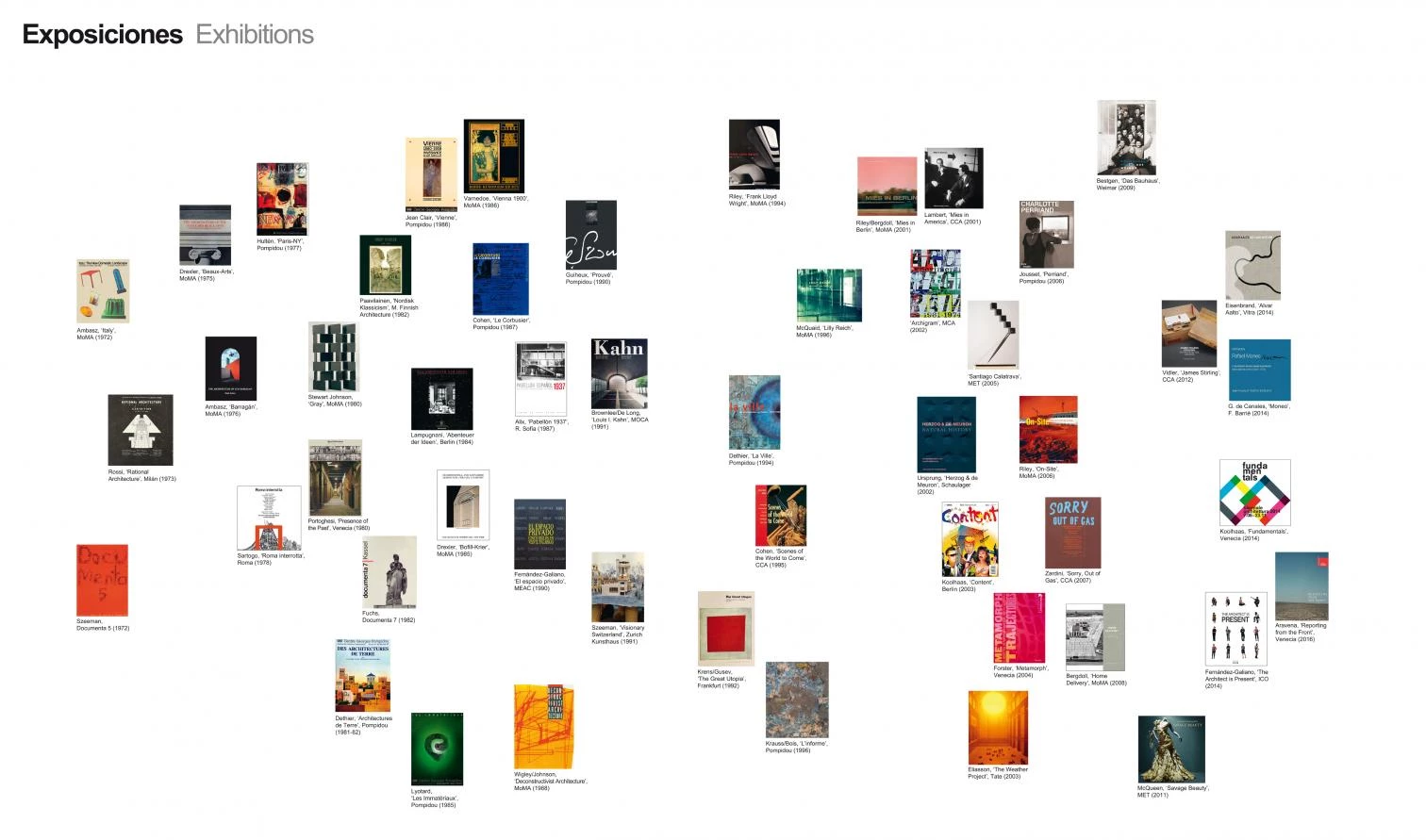

Here we have tried to come up with certain geographic balance, and the fifty exhibitions selected are spread out among twenty or so institutions and cities, but the fact is that two of them – the MoMA in New York and the Pompidou in Paris – have an inevitably dominant role, followed at a distance by the CCA in Montreal and the Venice Biennale, although in the latter case the size of the exhibitions and their impact surely compensate for the inclusion in this list of only four editions. The resulting map has an undue concentration in Europe and the US East Coast, but only because our experience is limited, and our knowledge of more remote geographies insufficient. Just like the books were dated by first printing in their original languages, these exhibitions are dated by the openings in their first venues, even though many have subsequently traveled to numerous other places, and in doing so perhaps alleviated the excessive concentration in benchmark institutions.

The chronological framework was set with the publication dates of the Rossi and Venturi books, and we may do well to remember how it was precisely the MoMA that in 1966 published the Venturi text as the first notebook of a series separate from its exhibition program. In fact this publication, with illustrations the size of postage stamps, had a limited reach, and most readers are familiar with the second edition that the museum itself released in 1977, with a landscape format and large images. In 1969 Arthur Drexler and Colin Rowe gathered in the museum five New York architects – called ‘whites’ because they were inspired by Le Corbusier’s villas – who would publish their work in book form in 1972, to be answered the following year, in Architectural Forum, by five ‘grays’ advocating realism with Venturian classicist accents, so the MoMA promoted contextual postmodern and Corbusian neomodern at the same time, justifying its centrality in the stylistic debates of the moment.

Eventually it was classicist postmodern that would have its way, scattering the five ‘whites’ in different directions, and Drexler himself organized a major exhibition on Beaux-Arts architecture that would fuel the antimodern reaction. Europe’s radical tendencies of the 1960s certified their exhaustion with the mythical Documenta 5 – curated by Harald Szeemann, who revised street actionism to again consider ‘the reality of visual representation’ within the museum’s walls –, which is still remembered for the poster of ants by Ed Ruscha and for the replacement of historiographic canons by individual mythologies. And the very dynamic Italian avant-garde similarly came to an end with two exhibitions that showed an artistic and intellectual change of direction: that of Emilio Ambasz at MoMA, on Italy’s new domestic landscape, and the Milan Triennale that Also Rossi curated in 1973.

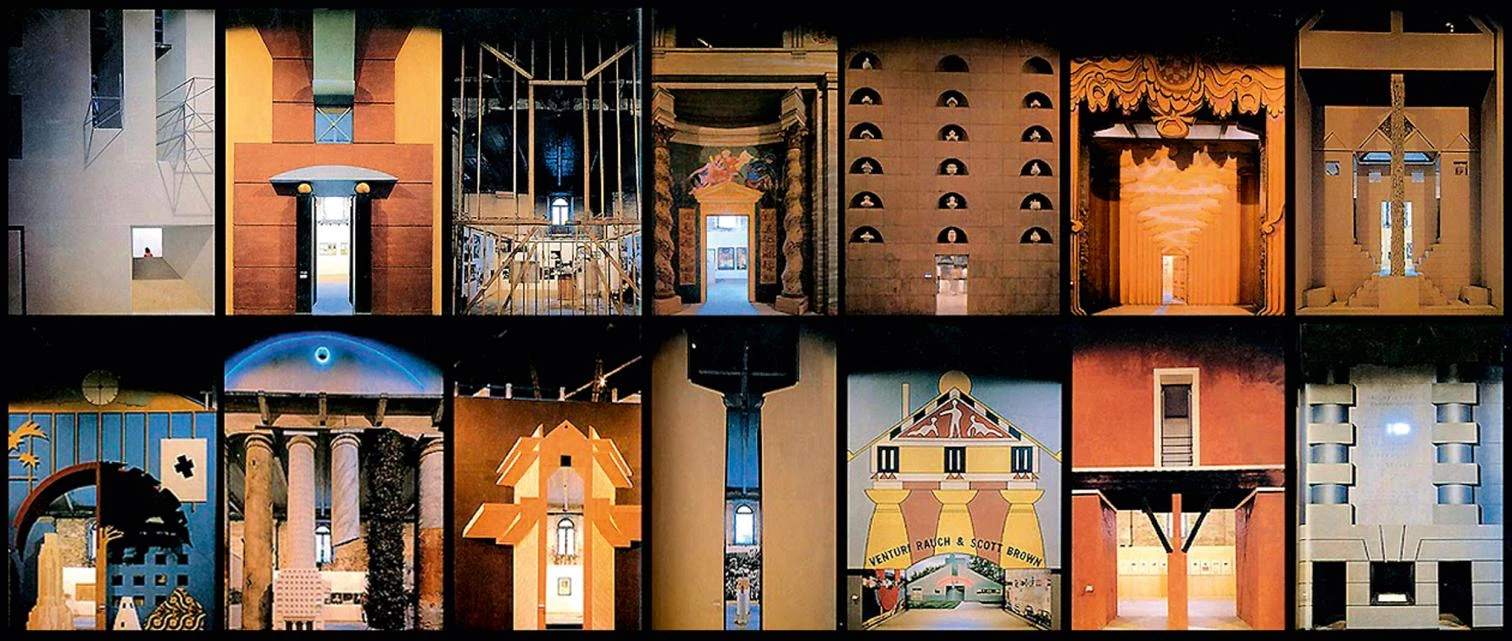

Postmodernity at its peak would be confirmed with two exceptionally influential Italian exhibitions, ‘Roma interrotta’ in 1978 and ‘La Strada Novissima’ in the 1980 Venice Biennale, organized by Paolo Portoghesi under the motto ‘The Presence of the Past.’

The architectural debate continued to move between Italy and the United States, but the inauguration of the Centre Pompidou in 1977 under the direction of Pontus Hultén created a new pole of creativity and thought. That same year the ‘Paris-New York’ exhibition, which presented cities as art and culture melting pots, initiated a monumental cycle (Paris-Berlin in 1978, Paris-Moscow in 1979, Paris-Paris in 1981) which the museum would prolong with other great shows, such as Jean Clair’s ‘Vienna’ in 1986 or ‘La Ville’ in 1993, a splendid synthesis of representations of the city and the thinking about it. But the 1980s were devotedly postmodern, and if the Finnish exhibited Nordic classicism, Rudi Fuchs’s Documenta 7 defended the aesthetic autonomy of art and its traditional values, Berlin launched IBA with an ideological and historicist show curated by Vittorio Magnago Lampugnani, and MoMA presented Ricardo Bofill and Léon Krier as examples of the new approach.

The exhibitions were also opportunities to revise knowledge of masters or to popularize the work of lesser known figures. So it was that Jean-Louis Cohen reconsidered Le Corbusier at the Pompidou in 1987, Brownlee and De Long dealt with Louis Kahn at the MOCA in 1991, Terry Riley tackled Wright at the MoMA in 1994, Mies was the object of simultaneous shows at the MoMA and the CCA in 2001, and Aalto was exhibited at Vitra in 2014. In the same way, architects like Barragán, Prouvé, or Stirling were given tributes in galleries and museums, female architects like Eileen Gray, Lily Reich, or Charlotte Perriand came out of the background, and contemporary figures like Rem Koolhaas, Herzog & de Meuron, Santiago Calatrava, or Rafael Moneo became known to the public at large. And often with the excuse of an anniversary, groups or movements like the constructivists, the Bauhaus, or Archigram were the subjects of exhibitions that mixed celebration with revision, and contemporary interests with historical research.

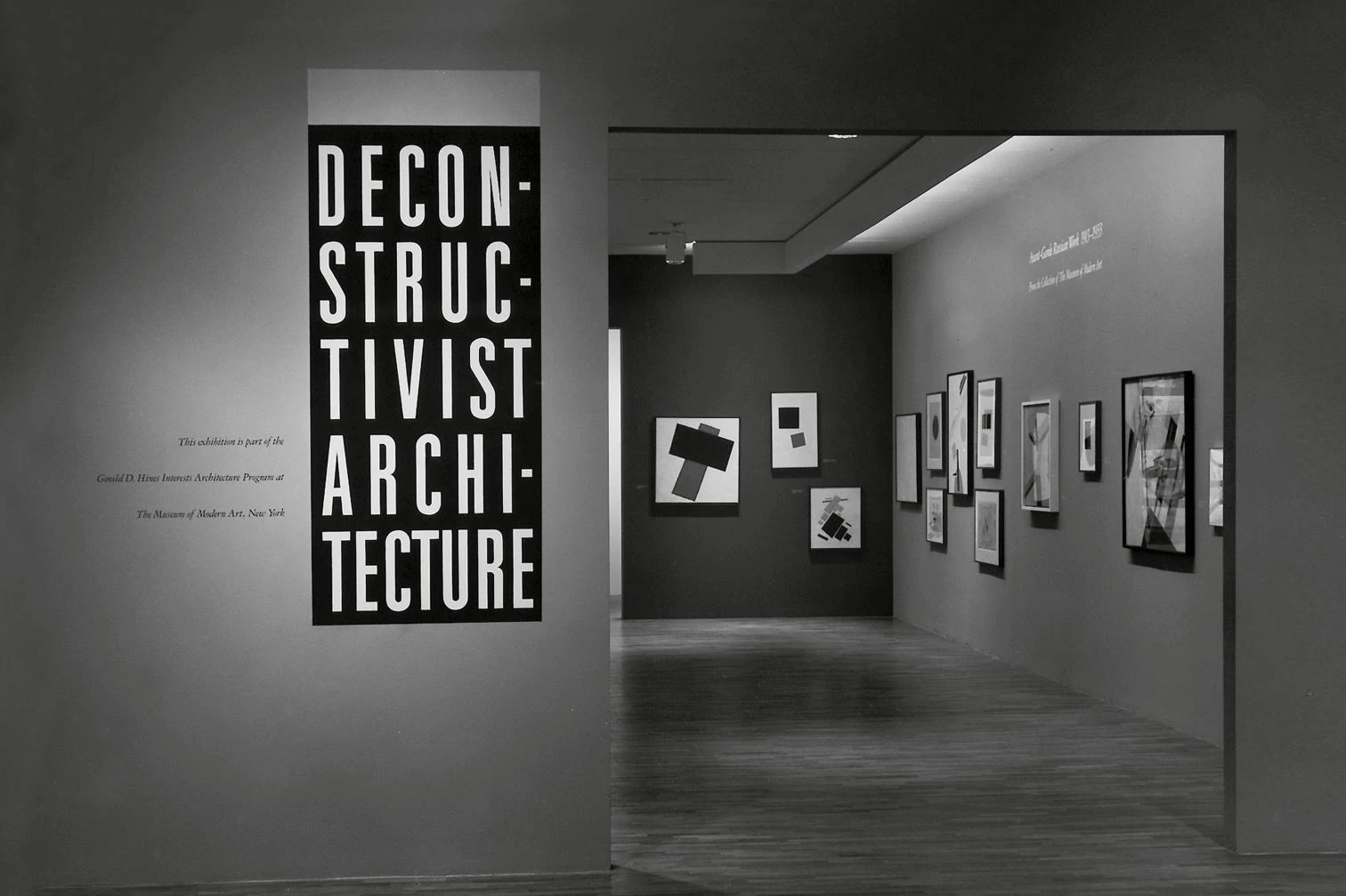

The climate of architecture changed in the late 1980s, coinciding with the end of the Cold War. No exhibition captured this as well as the one put together by Philip Johnson and Mark Wigley at MoMA in 1988, ‘Deconstructivist Architecture,’ an intelligent presentation of fractured works that would give its name to the dominant current of the 1990s, and which was said to be inspired in writings of the philosopher Jacques Derrida.

‘Des architectures de terre’ reflected at the Pompidou in 1980 the interest in the vernacular, while at the MoMA ‘Deconstructivist Architecture’ promoted in 1988 a renewed attention towards fractured and unstable constructions.

The Pompidou had begun to break away from traditionalism through Lyotard’s immaterials in 1985, and would go even farther than the deconstructive fractures with the ‘Formless’ of Rosalind Kraus and Yve-Alain Bois in 1996. But this deconstructive tendency would have as short a life as the classicist postmodernity it had replaced, and its swan song could perhaps be located in the Venice Biennale of 2004, directed by Kurt Forster under the title ‘Metamorph,’ which brought together many broken or catastrophic architectures that wanted to express the anguished nature of the times.

The urgencies of the energy and climate crisis also found expression in exhibitions that drew attention to the ecological debates of the 1960s and 1970s, and to the appreciation for the vernacular, the industrial, and the anonymous, breaking away from signature architectures and stylistic polemics. In 1964 Bernard Rudofsky had presented at the MoMA his programmatic ‘Architecture Without Architects,’ and this spirit was present in many later shows. In 1980 the Pompidou presented earth architectures as a traditionalist comeback, but Olafur Eliasson’s ‘Weather Project’ at the Tate in 2003, Mirko Zardini’s ‘Sorry, Out of Gas’ at the CCA in 2007, or Barry Bergdoll’s ‘Home Delivery’ at the MoMA in 2008 already agglutinated a new mood, attentive to the atmospheric, to energy, or the industrialization of construction. This intellectual and political environment would crystallize in the latest two Venice Biennales, the 2014 edition directed by Rem Koolhaas – which under the motto ‘Fundamentals’ explored the elements of architecture, as ‘Private Space’ at Madrid’s Museum of Contemporary Art had a quarter-century before – and the 2016 one piloted by Alejandro Aravena, which presented a new set of practices responsive to the needs of the planet and gave its Golden Lion to the Spanish Pavilion.

Our country, long absent from the main arenas of architectural debate, returned to them in recent decades, after the consolidation of democracy that was made visible by the homecoming of Guernica from New York’s MoMA, which the Reina Sofía celebrated with an exhibition on the 1937 pavilion that had been its first home. In 2006 Spain’s architectures were honored in an exhibition at the same MoMA, the museum’s first show focused on a country since the mythical ‘Brazil Builds’ of 1943, and the return to mainstream has been manifested through exhibitions like ‘Spaceship Earth,’ the monographic show on Buckminster Fuller at Ivorypress, or the presentation of emerging architectures of the Third World at the Museo ICO, titled ‘The Architect is Present’ (an ironic wink at Marina Abramovic ‘The Artist is Present’ at the MoMA), both shows setting the tone of a new era for those of us who, already in the Anthropocene, know we are just passengers of Spaceship Earth.

Spain had its exhibition at the MoMA in 2006, celebrating the works in a country that would face the crisis with shows like ‘The Architect is Present’ in 2014, also the year of a biennale that defended a return to fundamentals.

1967-2017

Cincuenta exposiciones

Emilio Ambasz, ‘Italy: The New Domestic Landscape’, MoMA (1972)

Harald Szeeman, ‘Befragung der Realität’, Documenta 5, Kassel (1972)

Aldo Rossi, ‘Rational Architecture’, Trienal de Milán (1973)

Arthur Drexler, ‘The Architecture of the École des Beaux-Arts’, MoMA (1975)

Emilio Ambasz, ‘The Architecture of Luis Barragán’, MoMA (1976)

Pontus Hultén, ‘Paris-New York’, Centre Pompidou (1977)

Piero Sartogo, ‘Roma interrotta’, Mercado de Trajano, Roma (1978)

Paolo Portoghesi, ‘The Presence of the Past’, Bienal de Venecia (1980)

J. Stewart Johnson, ‘Eileen Gray, designer’, MoMA (1980)

Jean Dethier, ‘Des Architectures de Terre’, Centre Pompidou (1981-82)

Simo Paavilainen, ‘Nordisk Klassicism’, M. of Finnish Architecture (1982)

Rudi Fuchs, ‘Sin título’, Documenta 7, Kassel (1982)

Vittorio M. Lampugnani, ‘Das Abenteuer der Ideen’, Berlín (1984)

Arthur Drexler,‘Ricardo Bofill and Léon Krier’, MoMA (1985)

Jean-François Lyotard, ‘Les Immatériaux’, Centre Pompidou (1985)

Jean Clair, ‘Vienne, Apocalypse Joyeuse’, Centre Pompidou (1986)

Kirk Varnedoe, ‘Vienna 1900: Art, Architecture & Design’, MoMA (1986)

Jean-Louis Cohen, ‘L’aventure Le Corbusier’, Centre Pompidou (1987)

Josefina Alix, ‘Pabellón Español. Exposición de París 1937’, MNCARS (1987)

Philip Johnson, Mark Wigley, ‘Deconstructivist Architecture’, MoMA (1988)

Raymond Guidot, Alain Guiheux, ‘Jean Prouvé’, Centre Pompidou (1990)

Luis Fernández-Galiano, ‘El espacio privado’, MEAC (1990)

David Brownlee, David De Long, ‘Louis I. Kahn’, MOCA (1991)

Harald Szeeman, ‘Visionary Switzerland’, Zurich (1991)

V. Gusev, T. Krens, ‘The Great Utopia’, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt (1992)

Terence Riley, ‘Frank Lloyd Wright: Architect’, MoMA (1994)

Jean Dethier, ‘La Ville’, Centre Pompidou (1994)

Jean-Louis Cohen, ‘Scenes of the World to Come’, CCA (1995)

Rosalind Krauss, Yve-Alain Bois, ‘L’informe’, Centre Pompidou (1996)

Matilda McQuaid, ‘Lilly Reich: Designer and Architect’, MoMA (1996)

Barry Bergdoll, Terence Riley, ‘Mies in Berlin’, MoMA (2001)

Phyllis Lambert, ‘Mies in America’, CCA (2001)

Philip Ursprung, ‘Herzog & de Meuron: Natural History’, Schaulager (2002)

AA, ‘Archigram: Experimental Architecture 1961-1974’, MCA (2002)

Olafur Eliasson, ‘The Weather Project’, Tate Modern (2003)

Rem Koolhaas, ‘Content’, Neue Nationalgalerie, Berlín (2003)

Kurt Forster, ‘Metamorph’, Bienal de Venecia (2004)

S. Calatrava, ‘Santiago Calatrava: Sculpture into Architecture’, MET (2005)

Marie-Laure Jousset, ‘Charlotte Perriand’, Centre Pompidou (2006)

Terence Riley, ‘On-Site: New Architecture in Spain’, MoMA (2006)

Mirko Zardini, ‘1973: Sorry, Out of Gas’, CCA (2007)

Barry Bergdoll, ‘Home Delivery’, MoMA (2008)

Ulrike Bestgen, ‘Das Bauhaus...’, Klassik Stiftung Weimar (2009)

Andrew Bolton, ‘Alexander McQueen, Savage Beauty’, MET (2011)

Anthony Vidler, ‘Notes from the Archive: James Frazer Stirling’, CCA (2012)

Jochen Eisenbrand, ‘Alvar Aalto’, Vitra Design Museum (2014)

Rem Koolhaas, ‘Fundamentals’, Bienal de Venecia (2014)

Francisco G. de Canales, ‘Moneo’, Fundación Barrié (2014)

Luis Fernández-Galiano, ‘The Architect is Present’, Museo ICO (2014)

Alejandro Aravena, ‘Reporting from the Front’, Bienal de Venecia (2016)